Women: Pennsylvania Abortions Left Us Sterile, Near Death

PHILADELPHIA (AP) -- Just days after Marie Smith got an abortion at a West Philadelphia clinic, her stomach swelled and she began vomiting green stuff.

Her mother, Johnnie Mae Smith, took her to a hospital where doctors rushed the unconscious 20-year-old into surgery to remove numerous fetal parts that were left inside her body, causing a potentially fatal infection. The doctor who performed the abortion, Kermit Gosnell, turned up at the hospital with his checkbook, aiming to settle immediately, the mother said.

Instead, Johnnie Mae Smith chased him away, vowing to sue. Later, her daughter got just $3,000 -- after lawyer fees—from a $5,000 settlement.

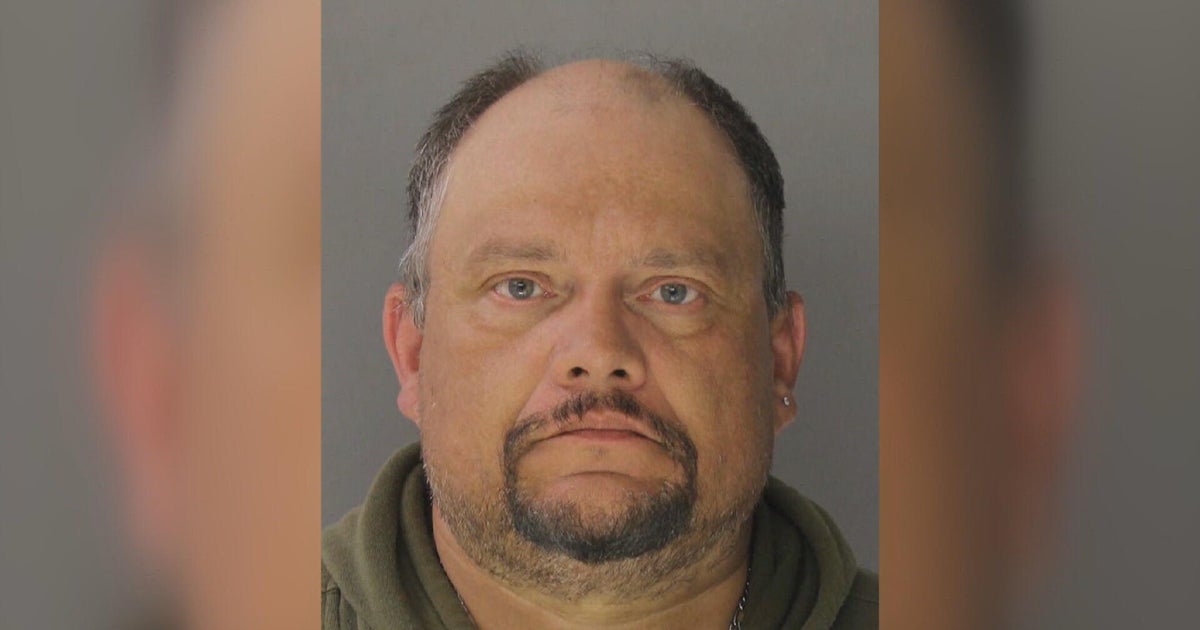

Gosnell, by contrast, took in at least $1.8 million a year from his corner-store medical practice at the Women's Medical Society, which prosecutors who charged him with eight counts of murder this week called his drug mill by day and abortion mill by night.

"His entire practice showed nothing but a callous disdain for the lives of his patients," Philadelphia prosecutors wrote in a ghoulish, nearly 300-page grand jury report released Wednesday. "His contempt for laws designed to protect patients' safety resulted in the death of Karnamaya Mongar."

The grand jury had scathing criticism for Pennsylvania state health and medical regulators who had numerous opportunities to shut Gosnell down over the years but ignored complaint after complaint about filthy conditions and illegal operations.

Gosnell was charged with killing seven babies born alive and with the death of Mongar, a 41-year-old refugee who prosecutors say died in 2009 after a botched abortion at the clinic. Unlicensed staff members gave her far too much anesthesia for her 4-foot-11-inch, 110-pound body hours before Gosnell arrived for his evening slate of abortions, a grand jury charged.

Mongar had fled Bhutan and had survived nearly 20 years in refugee camps in Nepal, even after cholera took the life of a 4-year-old daughter. She and her family had made it to the United States just four months earlier to pursue "all that America has to offer," said lawyer Bernard W. Smalley, who filed a medical malpractice lawsuit against Gosnell this week.

"She was the matriarch of their family and now she's no longer there. Her children will all have to be raised without her," Smalley told The Associated Press. "At the end of the day, this man has deprived her of her life."

He spoke for the family because Mongar's husband, Ash, a chicken farmer in western Virginia, does not speak English. Their three surviving children include a 22-year-old daughter, now working at a McDonald's, who had accompanied her 18-weeks-pregnant mother to Gosnell's clinic.

Another clinic in Virginia had referred them there because it did not do second-trimester abortions. Although Gosnell did not advertise, pregnant women throughout the mid-Atlantic learned through word of mouth about his Women's Medical Society in the city's impoverished Mantua section. Abortions are legal in Pennsylvania until 24 weeks, although many clinics won't do them past 20 weeks, or sometimes 12 weeks, unless the mother's health is in danger.

Gosnell routinely performed illegal third-trimester abortions, when babies are viable and the procedure is far more dangerous, authorities charged. One 17-year-old who was 30 weeks pregnant nearly died in 2008 after he tried to perform an abortion on her at 30 weeks, they said. The girl's great aunt had paid $2,500 in cash for the late-term procedure, they said.

Another girl, 14, went into labor and delivered a stillborn 29-week-old baby at a hospital after being dilated at Gosnell's clinic and then sent home, authorities said. She was supposed to return for the abortion later that Sunday, a day that Gosnell's unlicensed wife sometimes performed abortions, authorities said.

Gosnell was certified in family practice but had never finished an obstetrics/gynecology residency. In the words of Joanne Pescatore, a lead city prosecutor on the case, "He does not know how to do an abortion."

Gosnell perforated uteruses, bowels and cervixes of countless patients, the grand jury report charged. He left fetal parts inside them, ignored postoperative pain and bleeding and passed venereal diseases from one patient to the next through bloody and dirty instruments, the report said.

Davida Johnson first went to Planned Parenthood in downtown Philadelphia when she got pregnant in 2001. She was 21 and already had a 3-year-old girl at home.

"The picketers out there, they just scared me half to death," Johnson recalled this week. Someone sent her to Gosnell, saying abortion protesters wouldn't be a problem there. She said she paid him $400 cash.

Eyeing what she described as the dazed women in dirty, bloodstained recliners at the clinic, she had a change of heart as the procedure got under way.

"I said, 'I don't want to do this,' and he smacked me. They tied my hands and arms down and gave me more medication," Johnson, now 30, told The Associated Press.

She experienced gynecological problems a few months later. An examination revealed venereal disease, which she declined to identify. She blames Gosnell, 69, for the lifelong illness and for the four miscarriages she has subsequently suffered.

She learned only this week that prosecutors believe Gosnell frequently delivered babies alive, then severed their spines with scissors and stored the fetal bodies along with staff lunches in refrigerators at the clinic or severed their feet and lined them up in specimen jars, as if part of some unfathomably macabre collection.

"Did he do that to mine? Did he stab him in the neck?" Johnson asked at her North Philadelphia home this week. "Because I was out of it. I don't know what he did to my baby."

Johnson never sued over the abortion or ensuing venereal disease, but 46 other parties have, including the family of 22-year-old Semika Shaw, who prosecutors say died of sepsis at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in March 2002, two days after Gosnell perforated her uterus and cervix during an abortion.

Gosnell's insurer later settled the family's lawsuit over her death for $900,000 and referred a complaint and settlement to state health officials who oversee the clinic and Gosnell's medical license. The insurer's complaint brought no action, prosecutors said, because a Board of Medicine attorney said "the risk was inherent with the procedure."

In all, state officials failed to inspect the clinic, despite repeated complaints, from 1993 until January 2010, when a federal drug raid investigating heavy painkiller distribution at the clinic shut it down.

Gosnell by then ranked third in the state for the number of prescriptions he wrote for OxyContin, the highly addictive narcotic painkiller. Authorities allege that he left blank prescriptions for such drugs at his office and allowed staff to make them out to the cash-paying patients who streamed in during the day when he wasn't there.

Johnson's husband, Bobby, was one of Gosnell's pain patients. He said he went to Gosnell last year, paying $250 cash, to see the doctor about a debilitating pinched nerve. At the time, he said, he did not know his wife had gone to Gosnell years earlier, before they were married, for an abortion.

Gosnell typically worked from about 8 p.m. until after midnight, arriving only after his pregnant patients were dilated, sedated and ready for the abortion procedure.

During the day, his untrained or undertrained staff ran the clinic and practiced medicine there, authorities said. They ranged from two supposed "doctors" who had finished medical school but had no licenses to Ashley Baldwin, the 15-year-old daughter of office manager Tina Baldwin, prosecutors said. The teenager came after school to administer anesthesia and assist with abortions, even past midnight, the grand jury charged.

"As Ashley's involvement in Gosnell's illegal practices became deeper—at one point she was working 50-hour weeks and well past midnight, while trying to complete high school—Tina did nothing to curtail her minor daughter's exploitation by Gosnell," prosecutors wrote in the report.

Tina Baldwin, 45, is charged with corruption of minors and helping to run a corrupt enterprise. Nine other clinic workers are charged in the case.

Baldwin's husband, Michael Baldwin, told the AP this week that his wife got the Gosnell clinic job eight years ago after a business school she attended referred her there for an internship. She worked up front, taking cash from patients as they walked in.

Baldwin denied that his wife performed any medical tasks or witnessed anything untoward at Gosnell's clinic. Ashley worked in recovery, making sure the patients had clothes and a ride home, he said.

"How's she going to give anesthesia? My daughter's scared of needles," he said of Ashley, who is now 20 and pregnant and still works in the medical field.

The younger woman, who prosecutors said was present the night Mongar died, was not charged.

Both women cooperated throughout the yearlong grand jury probe, and the family was therefore stunned—and angered—by Tina Baldwin's pre-dawn arrest on Wednesday, Michael Baldwin said.

Gosnell, at his arraignment Thursday, said he did not understand why he was being charged with eight counts of murder.

"I understand the one count, because a patient died, but I didn't understand the seven counts," he told a magistrate.

The magistrate explained the other counts involved babies who prosecutors say were born alive, and she denied him bail. Four other clinic employees are charged with murder for roles prosecutors say they had in the death of Mongar or the viable babies.

Gosnell's wife, Pearl Gosnell, charged with performing illegal abortions and other crimes, is being held on $1 million bail.

Kermit Gosnell, in an interview with the Philadelphia Daily News after the clinic raid last year, described himself as someone who wanted to serve the poor and minorities in the neighborhood where he grew up and raised his six children. They include a doctor, a college professor and two children with Pearl who are still at home.

Defense lawyer William J. Brennan, who represented Gosnell during the investigation, said Gosnell "feels he has provided a general care medical facility in a fairly impoverished area for four decades."

"That's his belief," Brennan said, "and he's entitled to it."

Gosnell told the magistrate he's looking to retain another lawyer, and Brennan confirmed he's not representing Gosnell anymore.

"I wish him well, but I am not taking this case," Brennan said. "The doctor and I have had our run."

Marie Smith's mother recalls going to look for her only child at Gosnell's clinic when she did not emerge on time from the recovery room. She said what she saw shocked her.

"Nasty and dirty, filthy," Johnnie Mae Smith recalled this week. When her daughter took ill days later, she called Gosnell. "I said, 'What did you do to my daughter? ... My daughter's

about to die,' Smith said. "He said, 'Take her to the hospital."'

The $3,000 her daughter received from the court system hardly compensates for her suffering, she said. "That little bit of money they gave her, they could have kept

it. I'm glad she's got her life," Smith said. "All that money he made and all that money he has should go to the people that he hurt."

(© Copyright 2010 The Associated Press. All Rights Reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.)