Ultra-Marathoner Died From Heart Disease

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. (AP) — A 12-mile run for Micah True was like an easy cruise. The ultra-marathon runner was used to tackling more than four times that distance over much more grueling terrain and under the hot Mexican sun.

His body became conditioned with many miles under his belt, years of training and a diet with few vices — aside from the occasional beer or scoop of vanilla ice cream.

Because he was in such superb shape, his death during a routine run through the Gila Wilderness of southwestern New Mexico in late March surprised his friends and fans.

It's been more than five weeks since his body was recovered. Medical examiners have done their autopsy and released the results, but friends are still left guessing whether genetics or something else is to blame for stopping the man known as "Caballo Blanco" in his tracks.

"It doesn't fit with him going on a two-hour run. It wasn't exceptionally hot. By a lot of ultra-marathoners' standards, it was pretty simple," said Scott Jurek, one of the top ultra-runners in the world who knew True and helped search for him. "I doubt he was running that hard. I think it was just a matter of timing."

An autopsy report released Tuesday by the Office of the Medical Investigator showed the 58-year-old runner had cardiomyopathy, a disease that results in the heart becoming enlarged.

While medical examiners couldn't point to the cause of the heart disease, they said True's left ventricle, the chamber of the heart that pumps oxygenated blood to the rest of the body, had become thick and was dilated. That can result in an irregular heartbeat during exertion.

For athletes who spend a lot of time on the trail, Jurek said it's not unusual for them to have larger left ventricles. He suggested that many ultra-marathoners developed the trait over years of conditioning their bodies to travel such vast distances.

A sport considered insane by some, ultra-runners will argue that the human body was made for running. It's what humans used to do to survive in the wild. But more than that, they say, it's about listening to their bodies, finding an inner peace and enjoying the scenery at the same time.

True boiled it down to having fun.

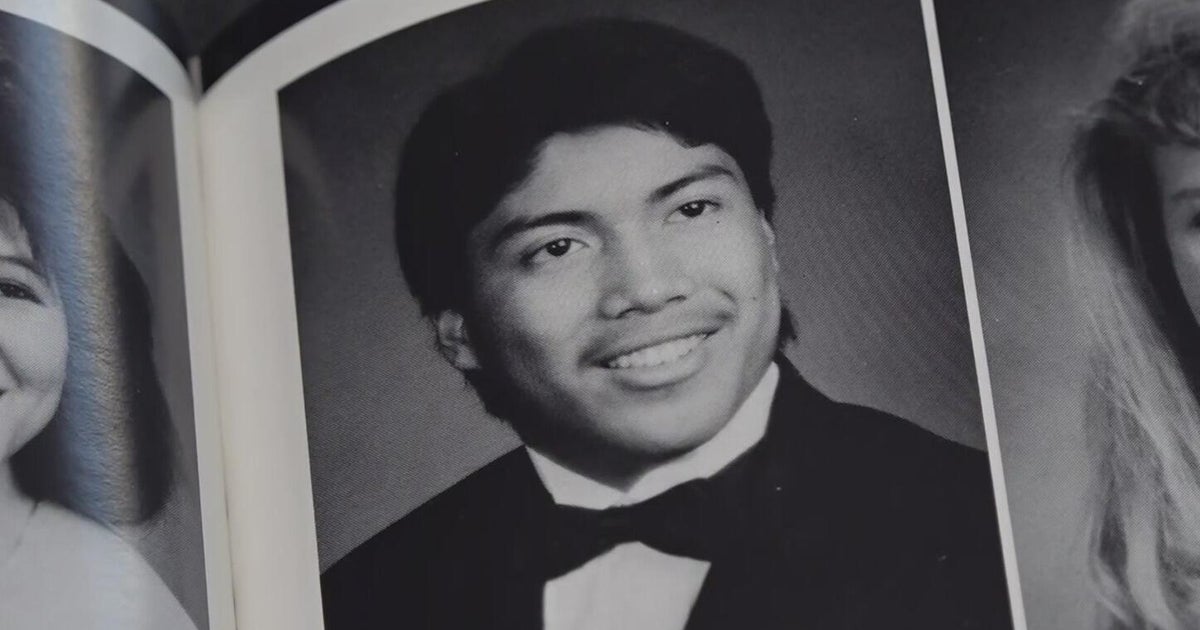

Remembered as a legend and an inspiration among runners, True, nicknamed "Caballo Blanco," was known for his big smile and infectious love of running.

He had been involved in ultra-marathons for years, but it wasn't until he became friends with the indigenous Tarahumara of Mexico that the direction of his life came into sharp focus. The Tarahumara are known for their extreme running prowess.

True spent much of the year living among the Tarahumara, or Raramuri, as they are also known. It was in the canyons where he got rid of his running shoes, put on a pair of sandals and learned to run the way the Tarahumara do — easy, light and smooth.

True's body was discovered March 31 along a stream in the Gila Wilderness north of Silver City, N.M. The search for him began days earlier after he failed to return from his run.

Chemical tests showed that True was mildly dehydrated and had caffeine in his system. He also had some abrasions on his elbows, forearms, knees and shins.

Friends theorized that he stopped at the stream to wash up after taking a tumble on the rugged terrain.

True's girlfriend, Maria Walton of Gilbert, Ariz., said True had no major health concerns.

"His only health issue was that he was hypoglycemic, and with no proper nutrition he would get dizzy or feel lightheaded. Not anything life endangering," Walton said.

"You know, at 6-2, 180 pounds, 31- to 32-inch waist, for a 58 year old man, that's pretty fit."

A disciplined eater, True would occasionally splurge and drink two beers when he wasn't running, Walton said. When friends would ask him if he had a vice, he would answer: "Vanilla ice cream," that Walton said came from a small market near where he died.

True founded the 50-mile-plus Copper Canyon race in Mexico and directed it for the last several years to highlight the Tarahumara's culture and their love for running. This year had marked a record turnout for the event, which sends participants, many wearing only sandals made of discarded tires, plunging into deep canyons and across mountains and rivers.

To his friends, True was healthy.

"This is a guy who could set out with a little bag of ground corn, a bottle of water in his hand and be gone all day. The day before he died, he did a six-hour run," said Chris McDougall, a friend and author of "Born to Run." The book chronicles True's efforts to develop the Copper Canyon race and draw international attention to the Tarahumara way of life.

For True's friends, no fingers can be pointed at ultra-running. They also dismiss the thought that True ran his body too hard.

True tried to set an example of healthy living knowing that death and disease due to poor eating habits and little exercise have become such major issues, Jurek said.

"That's something Micah stressed and lived every day, and he showed people that running is fun," Jurek said. "Tapping into old ways of living and breathing on this planet and just being immersed in the beauty of the world around you — that's really what he was about."