Quantum computers could solve problems in minutes that would take today's supercomputers millions of years

Advances in quantum computing are bringing us closer to a world where new types of computers may solve problems in minutes that would take today's supercomputers millions of years.

Today's transistor-based computers have their limitations, but quantum computers could give us answers to problems in physics, chemistry, engineering and medicine that currently seem impossible.

"There are many, many problems that are so complex that we can make that statement that, actually, classical computers will never be able to solve that problem, not now, not 100 years from now, not 1,000 years from now," IBM Director of Research Dario Gil said. "You actually require a different way to represent information and process information. That's what quantum gives you."

What is quantum computing?

Computers have processed information on transistors for decades, with advancements being made as companies squeeze more transistors onto chips. Faster, more powerful computing requires more transistors because each transistor holds information in only two states: zero or one.

Quantum computing ditches transistors and instead encodes information using qubits, which act like artificial atoms. Qubits aren't binary—they can be zero or one or anything in between.

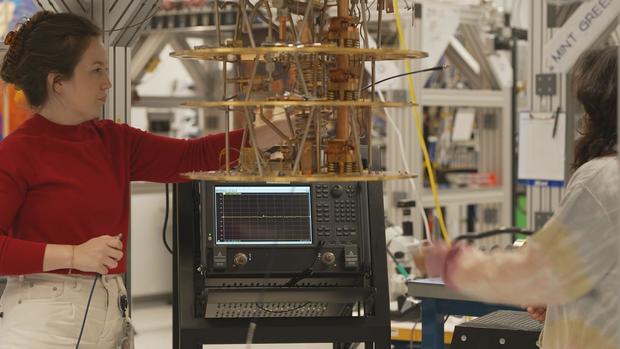

A reliable, general purpose, quantum computer is a tough climb. Charina Chou, chief operating officer at Google Quantum AI, showed 60 Minutes correspondent Scott Pelley the processor that holds the qubits at Google's quantum computer lab.

The sealed quantum computer at Google's lab is one of the coldest places in the universe, according to Chou. The deep freeze eliminates electrical resistance and isolates qubits from outside vibrations.

Companies and countries around the world are racing to be first to develop quantum computing technology. China named quantum a top national priority and the U.S. government is spending nearly a billion dollars a year on research.

What's so special about quantum computing?

Physicist Michio Kaku, of the City University of New York, already calls today's computers "classical." He uses a maze to explain quantum's difference.

"Let's look at a classical computer calculating how a mouse navigates a maze. It is painful. One by one, it has to map every single left turn, right turn, left turn, right turn before it finds the goal. Now a quantum computer scans all possible routes simultaneously. This is amazing," Kaku said. "How many turns are there? Hundreds of possible turns, right? Quantum computers do it all at once."

Kaku's book, "Quantum Supremacy," explains the stakes.

"We're looking at a race, a race between China, between IBM, Google, Microsoft, Honeywell," Kaku said. "All the big boys are in this race to create a workable, operationally efficient quantum computer. Because the nation or company that does this will rule the world economy."

It's not just the economy quantum computing could impact. A quantum computer is set up at Cleveland Clinic, where Chief Research Officer Dr. Serpil Erzurum believes the technology could revolutionize the world of health care.

Quantum computers can potentially model the behavior of proteins, the molecules that regulate all life, Erzurum said. Proteins change their shape to change their function in ways that are too complex to follow, but quantum computing could change that understanding.

"I need to understand the shape it's in when it's doing an interaction or a function that I don't want it to do for that patient. Cancer, autoimmunity — it's a problem," Dr. Erzurum said. "We are limited completely by the computational ability to look at the structure in real time for any, even one, molecule."

Quantum computers could also potentially break some of the encryption codes for today's online security. Next year, the federal government plans to publish a new standard for all encryption to resist quantum computers.

How close are we to a future with quantum computing?

Quantum researchers are still working on tough problems, including a trick called coherence. To achieve coherence, qubits must vibrate in unison, but maintaining this has been a challenge.

"We're making about one error in every hundred or so steps," Chou said. "Ultimately, we think we're going to need about one error in every million or so steps. That would probably be identified as one of the biggest barriers."

Still, the founder of Google's quantum lab, Hartmut Neven, feels optimistic the company can mitigate those errors, extend coherence time and scale up to larger machines.

"We don't need any more fundamental breakthroughs. We need little improvements here and there," Neven said. "We have all the pieces together. We just need to integrate them well to build larger and larger systems."

Neven believes this can be accomplished by the end of the decade. IBM's Gil also predicts around the same timeline.

IBM is set to unveil its latest quantum computer, Quantum System Two, on Monday. It has three times the qubits as the quantum computer at Cleveland Clinic. System Two has room to expand to thousands of qubits, Gil said.

"It's a machine unlike anything we have ever built," Gil said.

He sees a future with even more potential.

"We don't see an obstacle right now that would prevent us from building systems that will have tens of thousands and even a hundred thousand qubits working with each other," Gil said. "We are highly confident that we will get there."