Philadelphia Reaches Settlement In 'Stop And Frisk' Lawsuit

PHILADELPHIA (AP) -- A court-appointed monitor will oversee city police officers' use of "stop and frisk" searches, a high-profile part of the mayor's efforts to combat violent crime, according to a settlement agreement announced Tuesday.

Authorities also will take additional steps to make sure the stops are made only when there is reasonable suspicion of criminal conduct. The city also agreed to pay a total of $115,000 to seven of the plaintiffs, plus legal costs.

The settlement stems from a federal lawsuit filed by the American Civil Liberties Union in November alleging that the searches were violating the rights of blacks and Latinos who had done nothing wrong. The ACLU sued on behalf of eight men— including a state lawmaker—it says were subjected to illegal searches since the city started using "stop and frisk," a controversial element of Mayor Michael Nutter's 2007 election campaign.

As part of the agreement, the city denies wrongdoing and denies claims made by the plaintiffs.

Nutter said at a news conference that the city's auditing of such stops had become lax in recent years and that there will now be annual and quarterly reports. JoAnne Epps, dean of Temple University's law school, will serve as the outside auditor, Nutter said. The city also will make it easier for citizens to report police misconduct.

"The heart of the contract between citizens and police officers is trust," Nutter said. "We're going to make sure that the public has full confidence in this crime-fighting tool."

The city agreed to provide the plaintiffs with documentation of stops made during certain periods between 2006 and 2010. By January 1, it will enter reports into an online database, according to the agreement.

The city plans to review training on the searches and make sure that "stop and frisk" is only used when an officer has "reasonable suspicion" of criminal wrongdoing. Such stops aren't permissible, without limitation, where the officer has only anonymous information of criminal conduct or only because a person is loitering, engaged in "furtive movements" or acting suspiciously, according to the agreement. Such stops also cannot be done just because a person is in a high crime area or near where drug deals are known to be taking place.

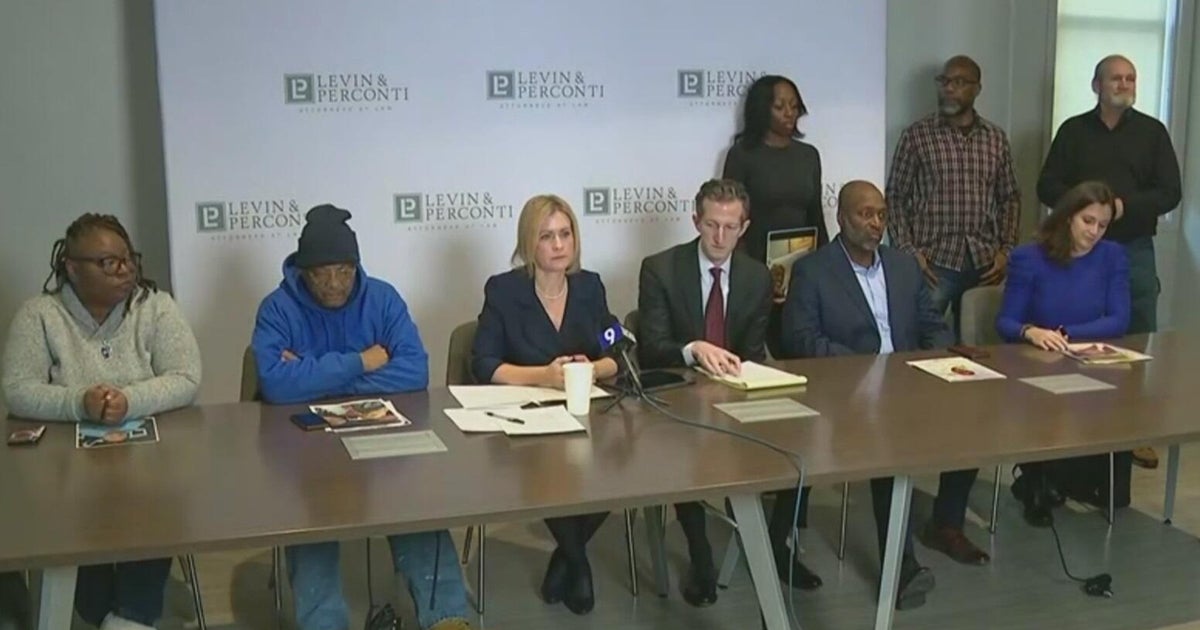

Paul Messing, an attorney for the plaintiffs, praised the settlement and said that it will help to reduce the number of innocent people who are stopped and detained for no reason.

"These kinds of unfortunate police-civilian encounters really tear at the fabric of police-community relations," Messing said.

In the lawsuit, the ACLU cited city data showing that 253,333 pedestrians were stopped in 2009, compared with 102,319 in 2005. More than 70 percent of the people stopped were black and only 8.4 percent of the total stops led to an arrest, the ACLU said.

The use of "stop and frisk" searches has been a focal point of Nutter's campaign to slow violent crime, which is down since he took office in 2008. Both Nutter and police Commissioner Charles Ramsey are black.

An officer making a pedestrian stop under "stop and frisk" must have a reasonable suspicion that a crime has been committed or is about to be committed, according to David Harris, a University of Pittsburgh law professor who is an expert on street stops.

In a typical stop, an officer will order the person to put their hands on a wall and then ask questions before beginning a search for weapons. If the officer is going to frisk, Harris said, he or she must suspect that the person is armed or that the crime they are suspected of requires a weapon.

Any policy like "stop and frisk" should be monitored carefully, Harris said, and Philadelphia was not alone in failing to do that.

"The vast majority of police departments do not track this activity," he said. "This should not be something that the public has to ask for or even go to court for. This is something that should be routine."

Nutter, who told the news conference he had been stopped numerous times during his life in Philadelphia, said the constitutional rights of everyone must be protected, regardless of race. But he also said that about that about 84.5 percent of homicide victims are black and that 84 percent of those arrested for homicide are black.

"Regardless of race, what we're concerned about is crime," Nutter said.

(Copyright 2011 by The Associated Press. All Rights Reserved.)