Keidel: Pro Football Meets Johnny Football

By Jason Keidel

The NFL Draft, pro football's ultimate red carpet gala, lived up to its hype last night at Radio City Music Hall, in the middle of Manhattan, in America's media vortex. There were more cameras, angles, and analysts in the auditorium than you'd find at a presidential debate.

And, of course, all eyes and iPhones were on Johnny Manziel, who squirmed in his seat for 21 picks before landing in the wasteland we call Cleveland. He forced a smile and his signature salutation, rubbing his thumb and forefinger, a metaphor for counting his cash.

The city celebrated like General MacArthur was strolling downtown in 1945. And maybe in September Manziel marches the Browns down the field for a winning field goal, stirring the masses and the media for a few weeks.

But what happens after the fall? When, to paraphrase John Facenda, the game becomes a duel in the rain and cold November mud? When the wind whips in from Lake Erie, and the monstrous arms of Big Ben and Joe Flacco fling the ball through the ornery winter snow? While Johnny Manziel falls face-first into the muck, crunched by Geno Atkins or Brett Keisel?

Brian Hoyer is getting the cosmetic decency of the starting job in May. But anyone with a pulse knows you draft Johnny Manziel to start Johnny Manziel. He's too famous, too fabulous, to squat on the pine. Especially in Cleveland, a town that lost its soul when LeBron James took his talents to South Beach, and hasn't won an NFL title since 1964.

That's not to say he can't play or play well. No player has ever burst into the NFL with more moxie and celebrity than Manziel, who also enters the league with the best handle in history: Johnny Football.

Johnny Football. He has his own, fictional nimbus, a movie star before he makes his first feature film. The pedigree is right. He comes from Texas, the soil that spawned 10 current, starting NFL quarterbacks. He was the first freshman to win the Heisman Trophy. He shredded Alabama. Twice. Something that no one has done to Nick Saban.

He was suspended for signing memorabilia, for which he says he was never paid. Sure. He's been all over the American map, photos snapped with Drake and LeBron and almost every teen idol with a Twitter account.

>>More NFL Draft Party Video Here

Bill Parcells famously said he doesn't want a Celebrity Quarterback. Is that Manziel? Is he more flash than fortitude? Or is he a secret gym rat who will dive into the job with the same fervor he gives his fame?

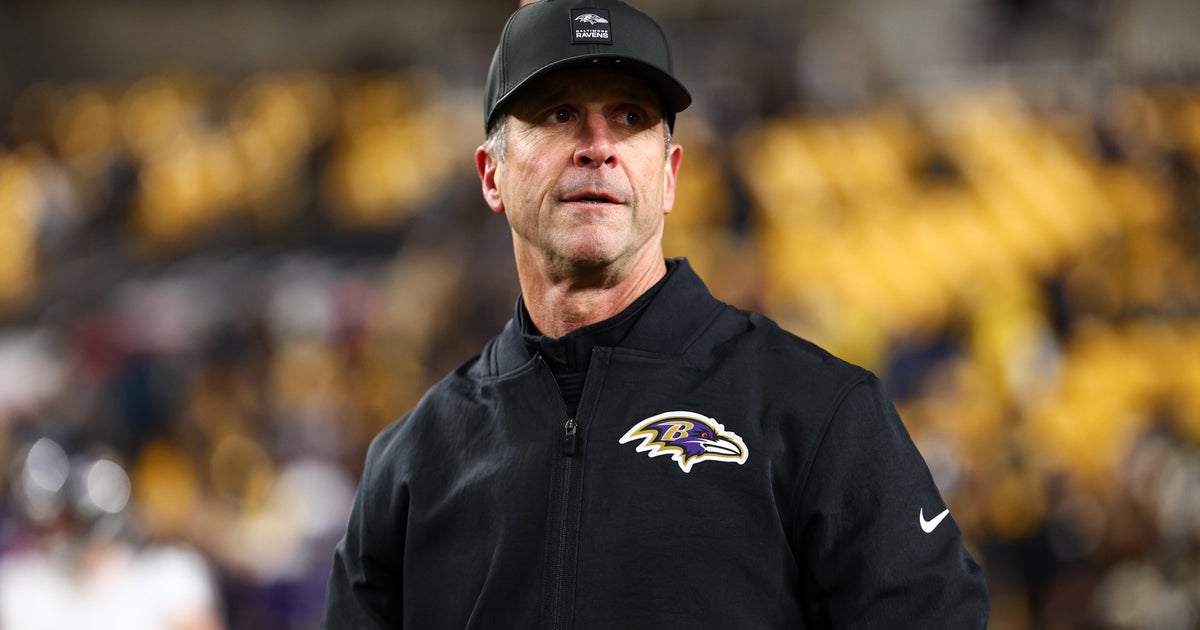

Manziel made countless millions for Texas A&M, and stands to do the same for the forlorn Browns, who haven't mattered since Marty Schottenheimer gave his "I have a gleam" speech in the 1980s. Since then, Art Modell moved the Browns to Baltimore and became the Ravens. Then the Browns returned, to pretty woeful reviews. Forgive the French, but the Browns have pretty much sucked since then.

But the beauty of Draft Day, beyond Kevin Costner's cinematic version (which also occurred in Cleveland), is the ephemeral hope and hype that comes with preseason dreams. Everyone is a contender in the spring, when players are young, healthy and newly wealthy. Boxers say a fight doesn't begin until you take your first hard punch. So it will be with Manziel this autumn.

Many of us wanted to see Manziel plucked by the Dallas Cowboys, the sport's most famous and dysfunctional team and the draft's most compelling figure. Jerry Jones, who adores the spotlight, actually drafted by need. Go figure.

Cleveland has needs, too. They need a lot more than Johnny Manziel. Do they even need Johnny Manziel? Can a team build from the ground-up with a player people expect to walk on water?

Johnny Football is a long way from Texas. But for the first time in a long time, the Browns matter. They've already sold 1,200 season tickets since last night. They're all there to see Johnny Manziel win. Will they stick around if he loses? For the first time in a long time, all eyes are on Cleveland.

Twitter: @JasonKeidel

Jason writes a weekly column for CBS Local Sports. He is a native New Yorker, sans the elitist sensibilities, and believes there's a world west of the Hudson River. A Yankees devotee and Steelers groupie, he has been scouring the forest of fertile NYC sports sections since the 1970s. He has written over 500 columns for WFAN/CBS NY, and also worked as a freelance writer for Sports Illustrated and Newsday subsidiary amNew York. He made his bones as a boxing writer, occasionally covering fights in Las Vegas, Atlantic City, but mostly inside Madison Square Garden.

You May Also Be Interested In These Stories