N.J. mayor shares message to East Palestine: "Protect your citizens"

PAULSBORO, N.J. (CBS) – The real-time environmental disaster unfolding in East Palestine, Ohio is stirring dreaded memories for a mayor in South Jersey. This isn't the first time the chemical vinyl chloride is in the spotlight.

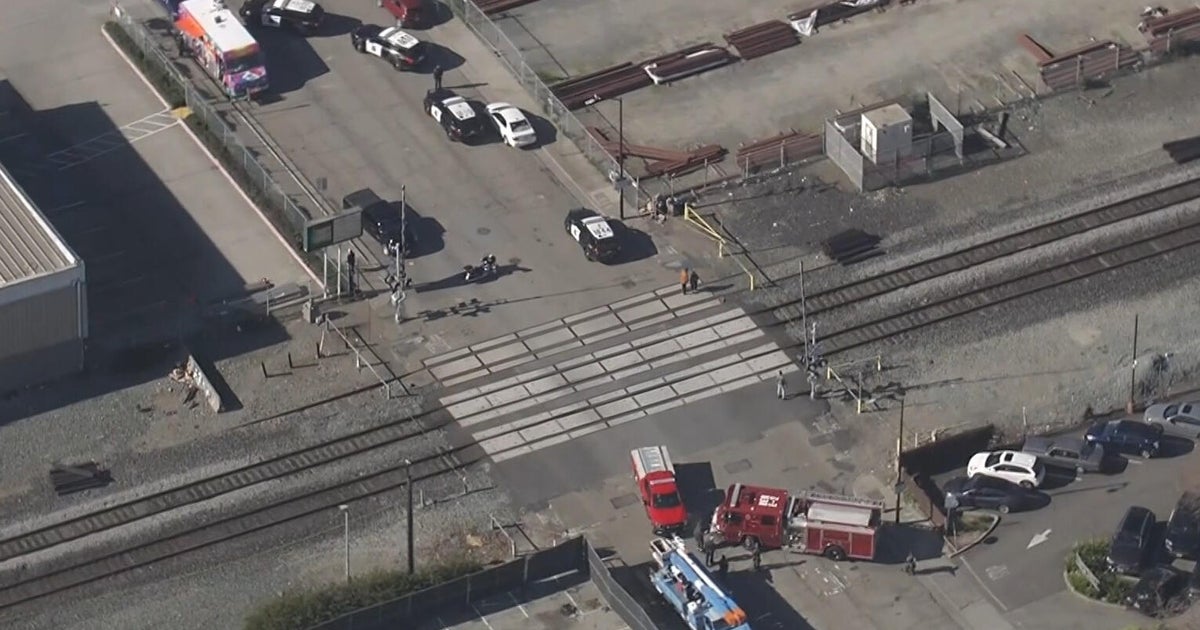

We're talking about the 2012 train wreck in Paulsboro, Gloucester County. A series of mistakes and a derailed train led to a 20,000-gallon leak of the toxic substance. That November morning, Paulsboro was blanketed in a toxic fog.

What's scary is the mayor says he believes little has been learned since.

The toxic nightmare unraveling hundreds of miles away is but a walk down memory lane for Paulsboro Mayor Gary Stevenson. The years that have gone by have not clouded unlike the air in town that cold November morning.

"You could not see your hand in front of your face," Stevenson said. "And that cloud swept right through town."

Much of the conversation focused on the 20,000 gallons of vinyl chloride released from a ruptured tanker.

Seven Conrail train cars derailed due to a train operator's decision to proceed across an unlocked swing bridge over Mantua Creek, according to federal investigators. At the time, Stevenson was on town council and an assistant fire chief.

His home was just feet from the derailment.

"The house literally rocked back and forth," Stevenson said. "The wife screamed, told me to get down here and hurry. When I came down, I was just enveloped by this fog. Oh [expletive]. Literally what I said, oh [expletive]."

Aside from the catastrophe, the National Transportation Safety Board would conclude a lot went wrong as people scrambled to understand the gravity of the disaster and the dangers of vinyl chloride.

The NTSB found there were delays in evacuations, a lack of protective equipment for first responders, a failure to move the incident command center away from the disaster site, and miscommunications, among other things.

Stevenson is haunted by the missteps, including the alleged downplay of vinyl chloride's toxicity.

The chemical is used to make PVC plastics and over-exposure can damage the liver.

"An officer said 'Oh, it's just fog,' and that kinda really skewered our whole response," Stevenson said.

Stevenson lived across the street from his parents, Walt and Irma, at the time of the crash.

"And then, when you see what's happening in Ohio," Irma Stevenson said. "I feel sorry for those people. At least we didn't have a fire."

Immediately after the Paulsboro crash, vinyl chloride, a potentially lethal carcinogen, was detected at 1,400 times higher than levels permitted by the federal Environmental Protection Agency, according to data in the NTSB report.

The air monitor that captured the reading was a full mile from the crash site.

Stevenson has a deep concern for the people of East Palestine, Ohio, especially the mayor.

"My first thing I'd say to him is: protect your citizens," Stevenson said. "Something should be set up by the federal government, with that mayor, with the state of Ohio that these people in that town are going to be tested regularly, and maybe by a third party or whoever, so that they know what's going to happen."

In the months and years after the crash, Stevenson says communication between Paulsboro leaders and Conrail has waned.

The NTSB specifically faulted railway personnel decisions, driving the train across the bridge despite a red light, and unaddressed bridge maintenance issues as reasons for the crash.

But Stevenson says the lingering damage is expected to surface years from now due to exposure to vinyl chloride. He says his doctors and a medical specialist he consulted with put it this way.

"In 15-20 years... your lungs will start to be bad," Stevenson said. "Your liver, something with the enzymes in the liver will start to go, and that's what he told me. I don't know. No one has ever come back to follow up with me and say 'hey we found this out about vinyl chloride,' that's what kinda I worry about with the people in Ohio."

Irma Stevenson remembers the Paulsboro derailment came with fanfare - ironic considering a train had just derailed.

"And the politicians, they came and set up their podiums and we [said] 'we're going to do this,'" she said.

Stevenson said those political promises dissipated much like that chemical fog.

But there are the haunting memories: the news cameras, officials and lawyers armed with what she says were non-disclosure agreements.

"They were mad because we wouldn't sign, and I said 'no, I'm getting my own lawyer," she said. "Well after that..." she made a cut-throat gesture.

"They were very nice until then," Irma added.

Gary Stevenson made a prediction — he expects the disaster in East Palestine, Ohio, to fade from the headlines in no time, like what he says happened in Paulsboro.

He argues maybe people think it wasn't that bad — but the "what-ifs" occupy his nightmares.

"The next seven cars were LPG, floating bombs, literally, bombs. if one of them went in, you and I wouldn't be having this conversation, half my town would be gone."

Why hasn't the incident gotten more attention?

"The only thing this isn't a lot more, is because no one's died," Stevenson said. "That takes it to a whole different level.

A federal investigation found several causes for the crash, including a locking mechanism that failed on the movable bridge crossing Mantua Creek.

The bridge rotated, the rails misaligned and the train derailed.

A fog of vinyl chloride emanated from a punctured tanker.

Hundreds were evacuated and some were kept away for weeks.

Because of his exposure, Stevenson said his doctors advised he should brace for health impacts.

The stigma of a toxic fallout zone cratered Paulsboro's Main Street economy.

The mayor says stores closed and businesses failed.

Despite the multiple investigations and probes — Stevenson isn't optimistic lessons have been learned.

"I guarantee you nothing has changed from 10 years ago," he said. "That could happen tomorrow."

And for this town bisected by rail lines, people here try not to dwell on worst-case scenarios — like the one a decade ago.

They go to work, and come home.

Irma Stevenson, now in her 70s, tells me she is still a fan of the night shift.

"'I'm a nurse, my husband is a barge captain for Exxon. We're all … damn hard workers."

What's next

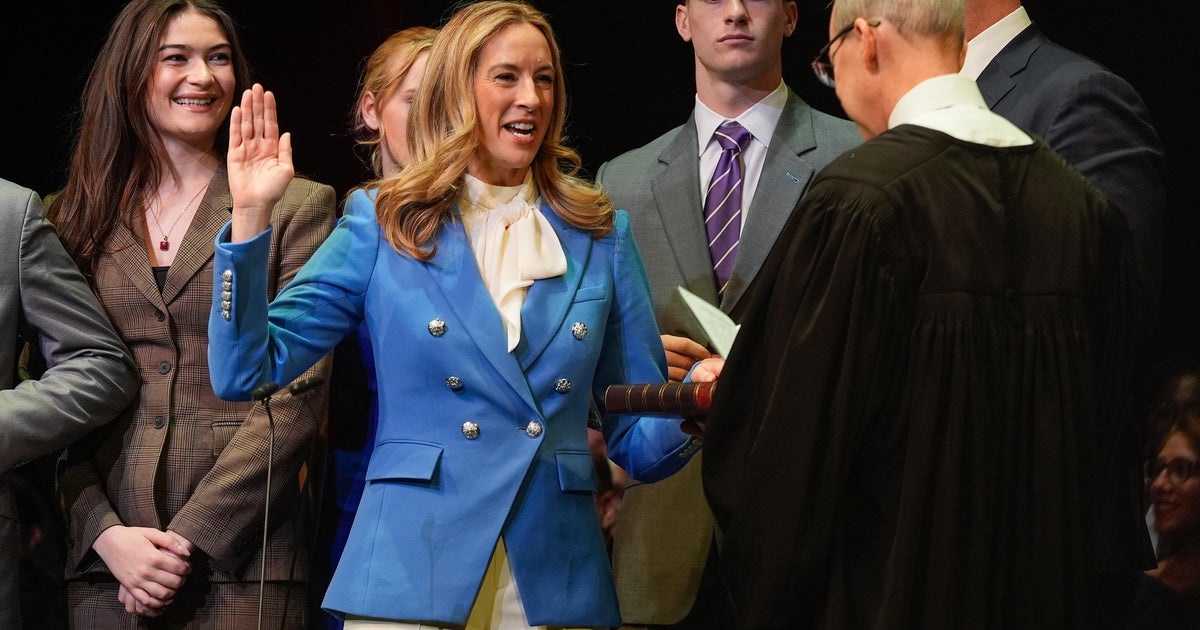

Mayor Gary Stevenson is expected to speak to lawmakers in Washington later this month -- about how Paulsboro cleaned up that vinyl chloride.

He told CBS News Philadelphia -- it was a long process riddled with mistakes.

Conrail responded to our requests for comment on this report with a statement:

"Conrail continues to support, prepare, and engage with local communities, stakeholders, and regional, state, and federal officials and agencies within our operating footprint to ensure the safe movement of freight."

In citing federal data, Conrail also added 99.9% of all hazardous materials reach their destination without incident.