Brain implant for seizures could help control binge eating

PHILADELPHIA (CBS) - Bingeing is the most common type of eating disorder, and now there could be a new breakthrough treatment for the most serious cases.

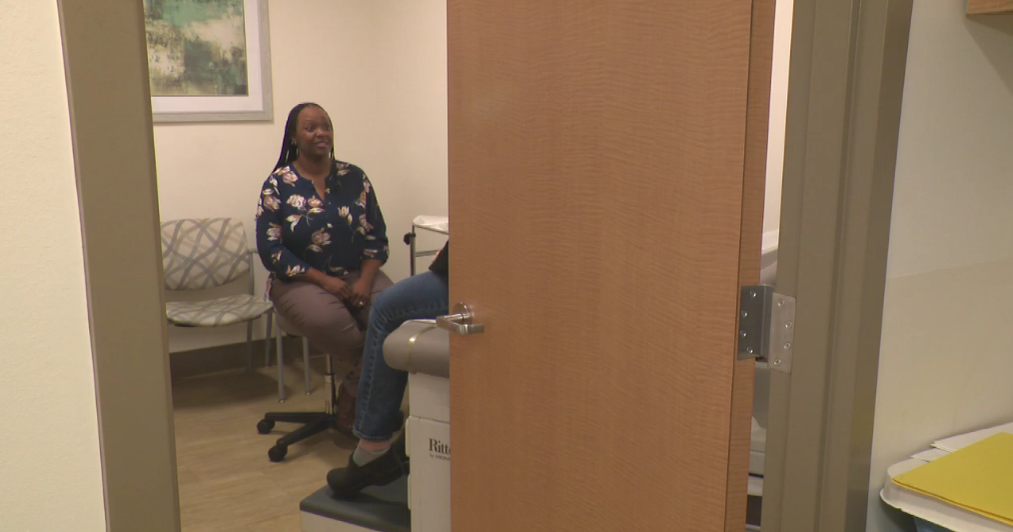

"Now I can go into the grocery store, look at the wall of ice cream, not even think about it," said patient Robyn Baldwin.

Baldwin no longer binges on ice cream or any of her other favorites.

"It's amazing the change that it has made in the way I eat food now," Baldwin said.

Baldwin is talking about a pacemaker-like device that's implanted in her brain designed to stop binge-eating impulses.

"You can actually thread a wire through this part of the brain because we know that's safe to do," Dr. Casey Halpern said.

Halpern, a neurosurgeon at Penn Medicine, is testing the brain implant on patients with severe binge eating disorder

"These are patients that really just cannot control how much they're eating," Halpern said.

The implant that provides deep-brain stimulation is FDA approved for patients with seizure disorders.

"The way it works in this case, is the device is able to detect a signal in the brain that relates to craving," Dr. Halpern said.

To pinpoint the exact location in the brain, the patient is kept awake during surgery and shown photos of their favorite foods.

"We had pictures of Mexican food, ice cream, chocolate cake," Dr. Halpern said. "We know what the brain signals are when these pictures are shown."

A tiny electrode is threaded to that part of the brain. It activates when it detects the person is having a craving.

"It's a mini zap that's not felt by the patient. They don't really know when the device is on or off, but their cravings are significantly less when the device is on," Dr. Halpern said.

Baldwin says she's lost 35 pounds, and for her, the invasive brain surgery - that she didn't feel - was worth it.

"I don't feel that it's working. If I touch my head, I can go 'Oh, yeah, that's where it's at.' But I can't feel anything that's going on," Baldwin said. "So it's been pretty fantastic.''

Halpern says the research is still very early and only available to patients who've failed other interventions, but it could eventually be expanded to treat different kinds of addiction disorders.