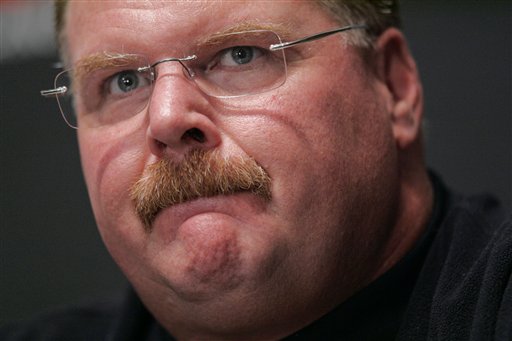

Andy Reid - A Father

PHILADELPHIA _ A boy fidgets in his mother's hold, as she repeatedly kisses his face. He recoils from her affection because he's eleven and they're outside in public and he'd rather keep playing catch with the football. But the day is fading fast, the way it does in autumn, the sun falling before supper.

PHILADELPHIA _ A boy fidgets in his mother's hold, as she repeatedly kisses his face. He recoils from her affection because he's eleven and they're outside in public and he'd rather keep playing catch with the football. But the day is fading fast, the way it does in autumn, the sun falling before supper.

She has a good arm, he thought. For a girl.

The boy scanned the horizon for other people. They were alone by the row of benches in the middle of the neighborhood park that is named after a French-born banker who singlehandedly saved the U.S. government from financial catastrophe during the War of 1812, just down the street from where a mobster called Chicken Man was blown up by a nail bomb placed under his front porch.

"Ma!" the boy whined.

She smiled down at him, knowing how boys are.

"Someday, you'll know."

Unbeknownst to the boy, her words would become as distinct and cherished as any family heirloom passed down to the next generation.

"Someday, God spares, you'll have a boy of your own. And you'll know."

She stepped back quickly, catching him off guard, and surprise-tossed him the football.

"But you can't know before then."

Andy Reid knows.

So he doesn't really have to ponder the question long.

The last few years have been rather trying for the head coach of the Philadelphia Eagles in that arena. Extremely trying. If only the troubles were about football. He could have fixed them. But they were outside the playbook. They were bigger and they were grave and they rendered him as helpless as a passenger of a car heading straight into another car.

Such an odd and uncomfortable position for him. See football coaches, by nature, are fixers. They're about conflict resolution. They're swift confronters. They attack a problem methodically, working from the edges inward. They're dogged and definite in doing it. Action equals consequence.

Early on this morning, one of the last quiet ones for him before training camp, Andy Reid lounges in a comfortable leather chair with his feet up on the coffee table in the center of his office. There is a window behind him that overlooks one of the practice fields, and several of the younger players on the Eagles roster work out down below.

He rubs his chin.

After all of these years, having raised five children with his wife Tammy, ranging from grade school to adulthood, he contemplates the core of fatherhood as he believes it.

"Unconditional love," he proclaims.

He says it like it's is final answer.

Unconditional love.

You don't define unconditional love, as much as you provide examples of it. Snapshots of it. A father accompanying his son to a drug rehab center and then sitting in another room trying to learn all about it and then bailing his other son out of jail and seeking drug treatment for him and then going back before a judge with his first son and then being holed up in the house as TV helicopters circle above and a horde of media advances to the edge of his property and then taking a leave from his high-profile job to undergo intensive support therapy and workshops and then visiting both sons in prison every week and then trying to help plan for their return and save their future and save their lives, all the while crying, pleading, hoping, praying, forgiving, loving and more loving.

Thirty years ago in that park that is walking distance from the Eagles' complex that houses Andy Reid's office, a woman named Florence explained to me that unconditional love cannot be measured by depth or by density or by unit. Therefore, it cannot be encased, even by the largest of ship canisters. That it's this bottomless well that could never be poisoned, in life or death.

That there is no medal from doing so. Because you don't weigh circumstance and seek reward. Because you just do, innately. You love the way you breathe.

She prefaced her message by saying as long as the parent wasn't soulless because only soulless people didn't love their children unconditionally. She added that there were certainly no Italian mothers who could be this way.

Or perhaps football coach fathers.

"I know it's complex," Andy Reid says. "There's a lot of things that go into parenting, obviously, but I guess if you break it all down, it comes down to unconditional love."

The test of unconditional love is pass/fail.

If you pass, you fail.

Sometimes it's a breeze, a football catch in Stephen Girard Park. Sometimes it's drugs and weapon charges and heinous stories and heartache. And for the Reid family, times that by two.

This story is not about the redemption of Garrett Reid.

This story is not about the redemption of Britt Reid.

Nor the sins of the sons.

It's about a football coach father who on Father's Day offers thanks that his entire family will be together without the constraint of visiting hours. The girls, Crosby and Drew Ann, and his youngest boy, Spencer, will be there, and so will Garrett and Britt, back making their way back in the world.

It's the story of a grateful man.

Andy Reid thanks me for asking about them. The boys. He thanks the town for its support during that period. He thanks everyone who reached out to him and the family. Stacks of correspondence. You can't imagine, he says. There are a lot of angels out there.

When he talks of the boys, he speaks in gratitude. Which sounds like another language, especially for a professional football coach; though, truthfully, Reid's locker room rhetoric has always been sodium-free, the way his Coke is caffeine-free, sanitized by his Mormon faith.

So he's very <italics>thankie<italics> right now, and who can blame him? His boys are out of the fire. Not out of the fight, something he's come to know as the father of addicts will never happen. But they aren't burning alive, losing their soul, sponging everyone else's worry, sapping their sorrow.

"Thank goodness," he says. He excitedly updates the status of his sons and begins with Britt – who "has been out a couple of years now and is attending a sports management program over at Temple and helps out with the Temple football program as a student assistant. Great opportunity Coach (Al) Golden gave him."

Garrett, meanwhile, recently graduated from a halfway house program where he worked at a body shop. A good family gave Garrett the job, just like a different good family gave Britt a job upon his release, a prerequisite for freedom. Reid balls his fist, "Good, hard manual labor. They were tough on him there, man. It's important to go through that. Now he's back and he just registered for school – a bold move. That's tough – as old as he is now – 27-years old."

So many opportunities by so many people, they were given, Andy Reid continues, and proceeds to thank a litany of people, beginning with the Montgomery County judge who publicly admonished he and his wife. Judge Steven T. O'Neill acknowledged that Andy and Tammy loved and supported their boys but called the Reids a "family in crisis."

"There isn't a structure that this court can depend on," O'Neill said at the time.

Reid shakes his head now in defense of the judge.

"He was painted as the bad guy because the judge kind of has a coach's mentality, tough love, you know? He really helped Britt get past this thing. There was quite a few people helping. Families helping. You find out when people are troubled, if they keep their nose clean and they come out and make a concerted effort to do right, people will step up to the plate and help and that's kind of the process."

In Reid's world, each day of the week means something, with Sunday, of course, being game day. The day after game day he'll review the tape many times, beginning in the middle of the night, and then he'll meet with his assistant coaches and his players and his training staff. Monday is the day to take inventory. Tuesday, the players are off, and he and the other coaches start formulating the game plan for the following game day. There are long practices on Wednesdays and Thursdays, as they institute the game plan for game day, followed by a light day on Friday. Saturday is a walk-through in the morning and team meetings at the hotel deep into the evening.

When the boys were inside, the only day that mattered was visiting day.

Thursday night.

"This isn't like breaking news," he says. "But I had the opportunity to go to these different jails and prisons and visit every week. So I was able to see where everyone was from. There's some great people in there. They did wrong but they got themselves in a bad situation where it was who they were hanging with or how they were brought up or some fleeting bad decision that changed their lives forever. There's some very intelligent people and very good people there and they're kind of doing their time."

Reid describes the scene with analysis. Trying to develop a read on the other inmates, the way he does with football players, which probably shouldn't be all that surprising. A friend of mine who is an undercover FBI agent says he can't turn it off, either. That he can tell whether the waiter is making up a story on why his wife's order came out wrong.

Andy Reid is talking about those Thursday nights … and coaching.

"You see these guys go through three phases," he remarks, stopping briefly to make sure we know this is strictly his observation. He infers that to mean untrained, which should really mean "not professionally trained." Because he's now a veteran of the system, by proxy, and when you know the insider lexicon of any subset, from prisoners to Parkinson's patients and facebookers to footballers, you know what you're talking about.

"I guess you try to break things down and learn it with your kids so you get a beat on it," Reid says. "But there's the phase that it's everybody else's fault, whether it's a judge doing me wrong or whatever excuse there is. Then they get to the realization that, `You know what? I screwed up. It's my fault. I messed up.' And then I think the third phase is the one that determines – or at least helps determine – a little bit of a future. You need a few breaks in that third phase, people helping you out. That third phase is, `Listen, I goofed up, and if they let me out, I will never, ever come back here.'"

I can see him there on a Thursday keenly watching the others, the way he does practice sometimes from the big perch in the sky, the crane that hovers about the field and offers a much different perspective.

"You can kind of sense the guys that have that frame of mind," he says. "They figured that out and then they take that next step when they come out. That's another transition. They're revved up and they know when their release date is and they're ready to attack the world and then they get let out into the world, you know, back into society here, and then they go, `Oh, no, this is a little scary.' This is deer in the headlights type deal, bright eyed, and uh, now what? `Who wants me? Is anybody going to give me a chance? I'm a convict.'

"That happens and you hope besides mom and dad that somebody reaches out and gives them an opportunity. Then you see the person gradually come back to their self. The insecurities start becoming confidence. Slowly."

Slowly.

Every day, as the father, you're a day watchman and a night watchman. Watching for old habits. Bad habits.

"It's kind of a long process and you just hope there's no stumbling block in between," he says. "That very easily could happen and it does happen quite often so you hope that they can get to the third phase. You hope that they really keep their mind on themselves. You help remind them to keep their mind on themselves. Every stage takes time and a lot of factors go into it. Being in jail is not an easy thing. Being in jail and kind of having a celebrity parent, I know that wasn't easy for them."

The whole ordeal played out so very public, the family's business strewn on the frontyard and in that affluent neighborhood with the sprawling stone homes protected by giant wrought-iron gates in suburban Philadelphia. Some twisted reality show, running repeatedly on the morning news and the evening news and the nightly news. These were boys of privilege running amok in the community, with guns, mind you, hardly sympathetic addicts without much of a chance from birth because of environs.

You can imagine what the villagers without empathy said. They sat in judgment of the parents because that's what happens when children of public people of privilege go wild and because it was two boys, not one, disproving in their minds the bad apple theory, and because this is a pro football town and so it's common knowledge Andy Reid's work week. They know full well that he slept in his office two, three nights a week during the season and that the rigors of NFL coaching can make turn even the best family men into absentee landlords.

You don't think Andy Reid himself wrestled with that notion? That he was besieged by guilt? That while the boys worked through their problems, Andy and Tammy endured sleepless nights wondering if those villagers were right? That they didn't retrace their every step? What could they have done differently? How did it turn out like this?

Along the way, like every other earnest parent with problem children, they felt like they were making the right choices, back to when they were a young couple just starting out and Andy was an assistant at San Francisco State and they lived in a small apartment and they mapped out a plan over an ice cream cone by the Wharf.

They thought they were blessed because she could stay home with the kids and the job offered great perks to secure the kids' future. And there was an offseason and the hours did shrink then to somewhat normalcy. They were able to spend real quality time together then, and maybe do these memorable family vacations. And besides, he had to work, right? What's the difference between the man who works two jobs so the kids can have a fulltime mother and the man who works one with the hours of two?

"You want to experience life," Reid says. "You want to experience all the good things there are to experience. Unfortunately in every family there's going to be some bumps in the road. Whatever it might be, it might not be addiction, it might be something else. I don't think you can sit there and stifle the growth because you're worried about all that stuff you have to still experience life and realize that there are still going to be some challenges. It's not the yellow brick road. There are going to be bumps and hurdles in the road and you got to work through it. One of the main things is you got to work through it together."

"My wife and I talked when this whole thing was going on," he continues. "You say that ten years down the road if those boys are okay and the family is doing well, that's all that matters. Somehow if this helped in some way, more power to it. When you have an addiction, you're never out of the woods but it's good to see that they're doing good and working to right their wrong. What looks like something that might tear your family apart can actually bring it closer together if everyone is willing to put things out on the table and not hide their emotions."

Andy Reid wouldn't say that the whole ordeal made him a changed man. That's a little dramatic, however drama-filled the whole ordeal.

"I think it altered my outlook when it came to Michael Vick," he says. "I think being a coach helped me with the situation and I also think this situation helped me be a coach. I say that because I'm dealing with all kinds of people here, and listen, when you got 80 guys, they all have families and they have situations they have to deal with. I've seen a few. I'm dealing with people so I see that part of it and I see some of the struggles that some of the players go through.

"I think the actual exposure that I faced and went through for this problem helped me to be more sensitive to their situations. It surely helped me with Michael. Just knowing the phases that he went through, knowing what to look for, and then in return making sure that he stays on top of his game.

"He seemed like he had the weight of the world on his shoulders when he got here. It's hard. You're saying all the right things. But it's an insecure ride the whole way when you get out of jail. He's a different guy today when you talk to him than he was back then. And as long as he keeps his nose clean, he will continue to progress and be better for it down the road."

Andy Reid is talking about Michael Vick. But if you listen closely, he's talking about the boys again.

For now, he can take a breath.

And he is grateful.