Transcript: Dr. Michael Osterholm speaks with Michael Morell on "Intelligence Matters"

In this episode of "Intelligence Matters," host Michael Morell speaks with top infectious disease epidemiologist Dr. Michael Osterholm, who is also director of the Center for Infectious Disease at the University of Minnesota, about the world's past, present and future handling of the coronavirus pandemic. Osterholm and Morell discuss the essential, still unanswered, questions surrounding vaccine and antiviral production and their manufacturing and distribution to the cities and countries that need them most. Osterholm explains why this virus is unlike any predecessor, and why so many mysteries about its transmission remain. He also explains how China's early handling of the outbreak may or may not have affected the effectiveness of other countries' responses. "Intelligence Matters" has dedicated a series of episodes to understanding the fundamentals and national security implications of COVID-19.

Highlights:

- COMPARISONS: "When you think about in the last hundred years, this virus has done something that no other disease has done since 1918 and the major Swine Flu pandemic of 1819 and 1820. Some sixty five days ago, this virus, SARS-CoV-2, was not even in the top 100 causes of death in this country. Within short order, it became the number one cause of death in this country. No other diseases have done that. This is remarkable. And so, yes, at the outset, we have to understand this is a real problem."

- VIRUS BEHAVIOR: "[T]his virus acts under a very, what I would say, is essential law of physics, and that is viral gravity, just like physics, gravity. If you drop a book, you'll hit the floor. This virus is going to keep going. It's going to keep being transmitted by people until it basically runs out of people to infect and until there are so many people who have been previously infected that they're like rods in the virus transmission reaction. We slow that down and that's what herd immunity gives us. So we just have to count on this virus continuing to transmit."

- VACCINE CHALLENGES: "The other challenge we have, which we haven't really addressed yet at all, is critical. And that is how will this vaccine be manufactured and distributed? So let's just say we have a vaccine in the United States or we have one in China ore have one in Europe. If, in fact, the first parties to get these vaccines and get them made, how are they going to share the vaccine? Are they are they going to make it available to low and middle income countries? if China gets a vaccine first, will the U.S. have access to that? If we get a vaccine first, will we share with the Chinese and Europeans? I can guarantee you that we will not have nearly enough in the earliest years, not just days of this pandemic, just in terms of manufacturing, distribution...Now, I don't want to see us get to a point where we have a vaccine, we can make it, and as the vial comes off the machine, we have no idea how or where it's going to be used. And we're going to be in a debate with that for some time. That would be really a truly tragic situation."

- VACCINE TIMING: "I do think that the vaccine availability is not going to occur anywhere near where some of the very optimistic estimates have been of early next year. I think to get an effective vaccine, even with all the the possible shortcuts that we can take without challenging safety or to determine how well it works means that we're well into next year at the earliest before we have a vaccine. And of course, this pandemic may have played itself out largely before that could even happen."

- EARLY STEPS TO LIMIT TRANSMISSION: "We're not driving this tiger, we're riding it. And what I mean by that is, is that when you have a respiratory transmitted virus like this, it clearly is a situation where what humans can do to limit transmission short of a globally available vaccine is very limited."

Download, rate and subscribe here: iTunes, Spotify and Stitcher.

INTELLIGENCE MATTERS – DR. MICHAEL OSTERHOLM

MICHAEL MORELL:

Dr. Osterholm, welcome to Intelligence Matters. It is great to have you. I know you're extremely busy, so we appreciate you taking the time with us. I'd love to start with a paper that your institute published on April 30th titled, "The Future of the Kovik 19 Pandemic. Lessons Learned from Pandemic Influenza."

I'm going to ask you a couple of questions about that paper? Why did you choose to look for lessons in past influenza pandemics rather than in past coronavirus outbreaks?

DR. MICHAEL OSTERHOLM:

Well, first of all, thank you, Michael, it's great to be with you today. There are actually several reasons for why we did this. Number one, is let's just take coronaviruses in general and the family of coronaviruses, which, of course, the SARS-CoV-2 is one member.

It turns out that the two models that we have looked at in the past with coronaviruses are ones of a seasonal type of virus. Ones that typically cause a common cold or in one instance, it can cause some pneumonia. And those are, in fact, seasonal only and not one that at all mimics what we're seeing with the current coronavirus. The second model is the SARS and MERS version. This severe acute respiratory distress syndrome, which first emerged in China in the fall of 2002, made its way out of China by the Guangdong Province into Hong Kong in 2003 and this spread around the world. MERS, which emerged in 2012 on the Arabian Peninsula and again, has continued to be a problem in that area with humans.

In both instances, those diseases were very different. Number one, is while the SARS disappeared from – you might say temporarily at least, we hope – in terms of the disease problems because we recognize what the animal reservoir was, where the source of the virus in the markets of Guangdong province and those were eliminated. And then humans that turned out were really most infectious in day five, six or seven of their illness, not earlier. And so once we understood that, we can identify potentially infected individuals, isolate them and really bring transmission to zero, and that eventually resulted in the elimination of SARS as we know it.

MERS is a bit more complicated because that virus actually is in dromedaries or camels. There's about one point seven million camels on the Arabian Peninsula. No one is going to put down camels like that. And so the virus continues to pain humans on the Arabian Peninsula. But again, like SARS, one is not infectious really till the fifth or sixth day. And so by early identification of patients, we get them isolated and again, stop ongoing transmission.

With the virus we're dealing with now, the SARS-CoV-2, it appears to have taken on many of the properties of influenza. One is likely most infectious before onset of symptoms and maybe in the first day or two of illness. And that is very much like flu in that regard, in that you're not going to stop it the same way you would MERS or SARS, because it's got later transmission.

The way that it began transmission in Wuhan and Hubei province was very much like influenza with relatively high transmission of anyone infected, individuals to others. And so we immediately began to think of it like influenza.

Based on that concept or model, our group actually called it on January 20th and said that this was likely going to be a worldwide pandemic, that the transmission would be very much like influenza, and that by late February, early March, you'd see it around the world. And, of course, that's exactly how it unfolded.

But now we're at a point where the question is, will it be like previous influenza pandemics going forward as a coronavirus? And that's where the paper that we've published from our center was really all about. It was saying, if it's like an influenza pandemic, we would expect to see activity around the world potentially in this first wave, it would be sporadic, meaning it would occur in some locations, not others. And some of the locations that did occur could be serious, like we saw in New York and places like Italy, but that it wouldn't occur widely.

And unfortunately, so far, this virus has been acting like that. And so we surely can consider the possibility that it might then therefore over the summer actually begin to become much less of a problem like we would see with an influenza pandemic within this large wave that would occur five to six months or later after introduction. And that's what we worry about.

So we added to other models and said if it's not influenza, what might it look like? And we said, what if it's just a whole series of kind of smaller outbreaks that just keep occurring over and over again or that it is a virus that's just a slow burn. But the key underlying feature, all of these models or scenarios, is that we are currently in this country somewhere between five to 20 percent of the population are infected. Only in very few locations is it as high as 20 percent like New York. Most of the countries have five percent. For this virus to develop what we call herd immunity, where there's enough transmission in the population with people becoming infected and develop what, we hope, is long term immunity – we don't know that yet. It takes 60 to 70 percent of the population for that to happen with before the virus transmission will slow down. Now, we can get there also by vaccine, but I think none of us at this point are going to make that assumption, at least for the next 12 months, that we're going to have a vaccine.

MICHAEL MORELL:

So, Doctor, are the total number of deaths roughly the same in your three scenarios? And do you all have a sense of what that total is going to look like by the time we get to the end of this thing?

DR. MICHAEL OSTERHOLM:

Well, I think the first thing to do is just to add perspective for those who may doubt that this is a serious challenge.

When you think about in the last hundred years, this virus has done something that no other disease has done since 1918 and the major Swine Flu pandemic of 1819 and 1820. Some sixty five days ago, this virus, SARS-CoV-2, was not even in the top 100 causes of death in this country. Within short order, it became the number one cause of death in this country. No other diseases have done that. This is remarkable. And so, yes, at the outset, we have to understand this is a real problem.

In terms of how we get to that 60 or 70 percent, as I mentioned a moment ago, if we have a vaccine that can shortcut getting to that number and higher with a vaccine, then obviously we're going to reduce the number of cases or deaths. But if not, we have to anticipate that those 60 to 70 percent of people will include a lot of deaths.

Well, how many? Well, right now we're seeing increased number of deaths, particularly in what we call people with high risk co-morbidities, meaning underlying heart disease, kidney disease, certain blood cancers, certain lung cancers, and, of course, being overage. And then one that is more unique to the United States than it was, for example, in China, is obesity.

All of these play a role in what the actual mortality rate is or how many people die from this virus. You'll see lots of debates about, is it 1 percent or 0.1 percent, whatever. None of us know. I can only say that if you look at just a population of the United States and say, 330 million people, if let's say 50 percent get infected, which is lower than actual herd immunity, you're now talking about 165 million people. That's a lot of infections.

If you look at that population and just take what we have now for understanding of the clinical disease and these are data combined from China, from what we saw in Europe and what we see in the United States today is about 80 percent of those people will actually have very mild to hardly noticeable illness. If the remaining 20 percent of that 165 million, if you look at that, about 10 percent will seek medical care, but not need hospitalization. About 10 percent or half of that will need hospitalization. So now you're talking about 16.5 million people.

Of that 5 percent that will need not just hospitalization, but intensive care medicine, of that anywhere from 1.5 percent to 1 percent will die, or basically somewhere in the neighborhood of 800,000 to about 1.6 million people. That's where the number comes down by the time this thing is over with.

Now, hopefully with drug therapies that could become available before then, that could reduce the mortality rates. That would be great. Again, we can't count on that yet. And this gives you a sense of potential – We're seeing it when you look at what's happened. I mean, again, come back to that 5 to 20 percent with most of the country in the 5 percent. Think how much suffering, pain and death, as well as economic disruption has occurred with just 5 to 20 percent of the population impacted. And you can see that just even given the number of guests today, you know, well over 70,000 and marching north quickly, that at that 5 to 15 percent, that's not a hard stretch to imagine what it might be like if, in fact, you know 165 million people get infected.

MICHAEL MORELL:

So, Doctor, you have a 18 to 24 month timeline to get to herd immunity. And I'm wondering what that timeline assumes about shutdowns and social distancing. And I'm wondering if we end up doing more social distancing. Could that push that 18 to 24 month timeline out even further?

DR. MICHAEL OSTERHOLM

You know, Michael, we're really in this kind of, you might say, guard rail situation where on one side we're talking about locking down the country, much like was done in China with Wuhan and Hubei province. Which I think we all agree would be almost a death toll for society as we know it. It would be a major challenge. And I don't think sustainable for 18 months or more.

On the other side, you have if we do nothing, this virus will run rampant. It will basically threaten our health care system. We know that many, many deaths -- and in addition, not just among those with this virus infection, but people who have heart attacks, strokes, etc, who can't get medical care because our health care system is literally down.

In addition to that, the number of health care workers who will continue to be exposed and develop infection as a result of their work will only grow in leaps and bounds. So if you have those two extremes and we say, 'Well, you know what? Those are not going to work, either one.' We have what I think is this middle ground, what I consider threading the rope through the needle, where basically, 'How do we release society back into its everyday life by minimizing the number of people who might have severe disease, people who will go on to be more, much more likely to die?'

Unfortunately, about 40 percent of our population of adults have either heart disease, renal disease, have had one of these cancers or are obese. And that's a challenge. So we're trying to figure that out because, again, we can't live on either guardrail. And so the question is, what will happen if we put social or I like to call physical distancing in place, is that we have to figure out how do we integrate with people at the lowest risk of having infection back in society. Once they get infected, if they have durable immunity, meaning it's going to last for more than a couple of weeks, that's a great way to slow down transmission because they no longer can get infected if they're exposed, and they will no longer transmit to others.

And so we don't know how we'll get to that 60 or 70 percent in terms of can we change the outcome of deaths so we don't let people who, in that 60 or 70 percent get infected represent the population of at-risk people for severe disease. Or is that just going to be impossible? Will we regardless end up infecting many? And we just don't know.

I think the thing that if I had to leave your listeners with, one very important point, this virus acts under a very, what I would say, is essential law of physics, and that is viral gravity, just like physics, gravity. If you drop a book, you'll hit the floor. This virus is going to keep going. It's going to keep being transmitted by people until it basically runs out of people to infect and until there are so many people who have been previously infected that they're like rods in the virus transmission reaction. We slow that down and that's what herd immunity gives us. So we just have to count on this virus continuing to transmit.

MICHAEL MORELL:

One last question, Doctor, about the virus itself, and that's -- looking out even further, what happens to the virus and the disease on the other side of that 18 to 24 months? On the other side of the pandemic. We we hear that over time, the virus will evolve to be less virulent, less deadly. Is that true? If so, how does that happen? How long does it take? I guess what I'm asking is even after herd immunity drops the case load, you know, significantly. Are we looking at a future in which this virus is as deadly as the one today? And will it remain a mortal threat to those people with vulnerabilities, or is it going to evolve?

DR. MICHAEL OSTERHOLM

Well you are asking the multitrillion dollar question, and there are several issues there that we don't yet understand that are critical to giving you a final and correct answer. Number one, will the virus mutate or change and become less of a risk, meaning that it's a milder disease?

We don't know that. We don't have an experience like that would occur with a coronavirus. If it were flu, I can surely say yes that would happen. But that doesn't mean that it would go away, it becomes a seasonal flu virus and can still kill many thousands of people every year, even during the flu season. With the coronavirus, we're just in uncharted territory. We have to admit we don't know.

Second of all, can we make a vaccine against it? Will, in fact, what we can do actually cause individuals to develop immunity. And then how durable is that immunity? Does it last for a long time? Is it highly protective? We don't know that. We don't also know a third piece, which is. 'If I get infected with the virus, will I develop that same durable immunity that I might get from a vaccine? And if so, how long does it last? How protective is it?'

So we just have to be honest and say we don't know these answers yet. We have data in a limited way suggesting, number one, that there is at least short-term immunity. People get better. So your body must be fighting off the virus, and some successfully.

Number two is we've had several animal studies done where certain monkey species, which mimic what we see in humans in terms of infection and disease have been given the virus. They've recovered after having been ill and then they've been challenged again and they were protected. The same thing is true with two of the vaccines that are being evaluated right now. The monkeys were vaccinated and then subsequently they were challenged with the virus and they showed protection. So that's good news. But the long and short of it is we don't know how long that protection might last and what it means.

So to say what it's like on the other end, you have laid out a very important scenario that we all don't want to think about, but must think about it. And that is, 'What if we can't get long term protection? What if this virus doesn't change and become a more muted or a virus that doesn't causes severe disease?' And we just don't know what the answers are to those yet. But they're absolutely critical questions we have to have answered.

MICHAEL MORELL:

So, Doctor, maybe we can keep with the vaccine theme here. How do you think about a vaccine from the perspective of of actually getting to one? And then how long that would take? What's your sense?

DR. MICHARL OSTERHOLM

Well, there's actually a series of steps here that all are critical, and if all of them are not in place, we don't have a successful vaccine.

Number one is we have to figure out, with the more than 100 vaccine candidates we have today that represent different kinds of vaccines. Do any of them work? And what do I mean by work? Well, that's a challenge because we haven't really defined that yet. And what if we get a vaccine that only protects about 20 percent of the people? Is that one we're going to make and distribute worldwide?

Surely it's better than nothing. But is that an international enterprise that will roll? What if we get a vaccine that, of course, protects people 95 percent of the time, but we're not sure if it's long term immunity? We'll have to figure that out or we might be back that vaccinating people literally every year like we do for influenza.

The second piece, after if we get that, we still have to show that it's safe. And there are challenges with this kind of a virus vaccine, because we know that coronaviruses in general and specifically the SARS virus from 2003 actually can cause a condition when you're vaccinated for that virus and you get infected with the real virus, of what we call "antibody dependent enhancement."

This is a condition where you make a little bit of antibody as a result of the vaccine, and then you get infected, you may get this over-vigorous immune response enhancement kind of picture that can cause a shock-like condition and actually can be fatal. We saw that with the vaccine several years ago, a new one that had come out that caused children in the Philippines who were vaccinated to actually have very severe life-threatening infections, literally because of the vaccine. That vaccine obviously is not on the market anymore.

So we have to be certain that this vaccine is safe also. And how much safety will we demand of the vaccine is a question as to, well, what's the other side of the coin with the number of deaths that the disease itself will cause? So if we have a vaccine that one out of 100,000 people have a bad event with it, we surely may decide to go for it. This is still a much, much better option than X percent of people getting this infection and dying.

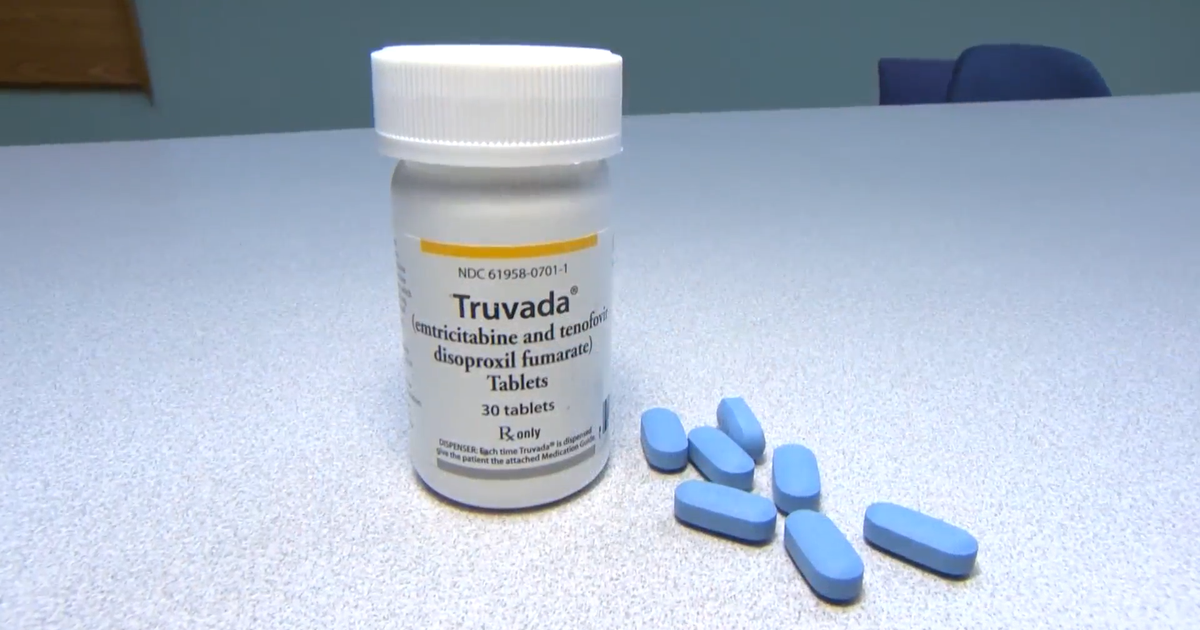

The other challenge we have, which we haven't really addressed yet at all, is critical. And that is how will this vaccine be manufactured and distributed? So let's just say we have a vaccine in the United States or we have one in China ore have one in Europe. If, in fact, the first parties to get these vaccines and get them made, how are they going to share the vaccine? Are they are they going to make it available to low and middle income countries? if China gets a vaccine first, will the U.S. have access to that?

If we get a vaccine first, will we share with the Chinese and Europeans? I can guarantee you that we will not have nearly enough in the earliest years, not just days of this pandemic, just in terms of manufacturing, distribution.

And so we need to come up with an international scheme that we all buy into that says this is how the vaccine that will made and distributed.

And then even within a country, we need to decide who gets it first. For example, in the United States, I could very strongly argue that the first group of people that should get this vaccine are health care workers. They're putting their life on the line every day, trying to provide the care to these patients and putting themselves at risk. Well, if we say health care workers are first in line, I can tell you there'll be a general outcry from many in the public saying, 'Wait a minute, they're taking care of their own first. That's not right.'

And so many medical, legal, ethical issues that are going to come up around this have to be addressed. Now, I don't want to see us get to a point where we have a vaccine, we can make it, and as the vial comes off the machine, we have no idea how or where it's going to be used. And we're going to be in a debate with that for some time. That would be really a truly tragic situation.

MICHAEL MORELL:

Just one more quick question on on a vaccine. Are there differences between vaccine development for influenzas and for coronaviruses that make the latter more or less challenging?

DR. MICHAEL OSTERHOLM:

Well, in fact, there are substantial differences between what we do currently for influenza vaccine and for coronavirus vaccine. Within the influenza vaccine area, we actually have really two large categories of vaccines. One is what we call egg-based production. We're actually growing the virus in chicken eggs and then harvesting that virus and then adding it to our vaccines.

The second one is where it's grown from the cell culture, meaning much like we do other traditional vaccines. And in some cases, there are things called adjuvants, chemicals to boost the response. There are different kinds of presentations. So that's the case there. We also have a number of different ways that we're looking at with regard to coronavirus. And one of the key ways that's being done right now is actually inserting genetic material into the hole, which is the vaccine.

And actually that genetic material then gets inside the human cells and it produces part of the virus in a way that that's what induces the immune response -- is to the actual particle production by your own cells in your body.

So that's one way, there's other ways that also being looked at that represent, you know, really the cutting edge of new modern vaccines. One day we hope the flu vaccine improves and gets to a similar place. So, yes, there are differences and the experimentation we're doing right now with the vaccines and the coronavirus are really very, very critical because they're not only going to teach us about what we can do with the coronavirus, but even modernizing all of our vaccine production one day down the road.

MICHAEL MORELL:

So, Doctor, thoughts on antiviral development?

DR. MICHAEL OSTERHOLM:

Right. If we can't get a vaccine. Of course, the next best thing is let's hopefully reduce the severity of disease and of course, deaths.

Now, one of the challenges we have with this virus infection that I mentioned earlier is that people are most infectious, literally in the days before they become ill, if they become ill at all, right up and through the earliest stages of illness. And that is what's driving the pandemic, that kind of transmission.

So we don't expect a drug to have any impact on that. So in other words, the cases will continue to occur. The point being, though, is among those who become ill, who is it that's going to more likely become seriously ill and then ultimately die? If we can find a drug that can be given to patients early on in their illness, that prevents them from becoming severely ill or dying, that would be still a major, major game changer.

And so that's what we're working on right now, are drugs like that. Now – the disease is very complicated. The more we learn about it, the more we realize how little we know about it. And there appears to be two totally different parts of this virus infection picture that have to be considered. One is the growth of the virus itself. And clearly, that's what we talk about, when we talk about antiviral drugs, we're trying to hold down that virus reproduction as if that's the primary reason why we're sick.

But we also have increasing data that it's also the immune response to the host. One of the key components is what we call acute respiratory distress syndrome, ARDS, which is an immune response that basically causes the shock-like picture in the individual. As well as we're seeing now, a type of inflammation, particularly inside of the blood vessels, which again, is an immune response that is actually causing blood clots to form and strokes to happen.

So the drug picture really is pursuing two totally different approaches. One is trying to deal with the virus itself, and one is trying to reduce the negative impact of the human immune response. What we'll have eventually, we don't know. And again, as I've shared with the vaccine itself, we also have to understand, when treatments do become available, if they do, how will they be distributed globally, how they can be distributed in the United States.

In the earliest days of the first drug that we've seen, come forward as a possible drug there've been great challenges in how it's been distributed. A lot of outcry from hospitals that they did not have access to the drug when others did. And so, again, we have the same challenges with drug manufacture and distribution we're going to have with a vaccine.

MICHAEL MORELL:

So, Doctor, kind of maybe this is an unfair question, but maybe the bottom line on vaccines and antivirals, should we be optimistic or pessimistic? What's your sense of the probability that we will get something in terms of a vaccine or an antiviral that will significantly shorten that 18 to 24 month time period that you're talking about?

DR. MICHAEL OSTERHOLM:

Well, first of all, it's not an unfair question; we're all asking the same question ourselves. So let me just say I hope we have both and soon, but we both also realize that's not a strategy.

And so I think that the likelihood of finding antivirals and immune suppressing drugs that will be helpful is real. I think we're going to find some of those. The question is, how much impact will they have? How many patients will actually have access to these drugs?

I can assure you that most of the world will not, because what's going to happen is going to occur largely in the next 12, 18 months, and just ramping up production of the drug and making it available worldwide would take far, much more time than that that we have. So I'm more optimistic on this side of the house. But again, I don't know how much impact it might have or not have.

As far as vaccines, the same is true. As I mentioned, we have data from at least early vaccine studies in subhuman primates, monkeys, that there may be some protection. What we don't have any clue on is how long that might last, how complete that protection might be, and just how safe the vaccines will be. So I think that's all possible.

I do think that the vaccine availability is not going to occur anywhere near where some of the very optimistic estimates have been of early next year. I think to get an effective vaccine, even with all the the possible shortcuts that we can take without challenging safety or to determine how well it works means that we're well into next year at the earliest before we have a vaccine. And of course, this pandemic may have played itself out largely before that could even happen.

MICHAEL MORELL:

Doctor, there's a there's a lot of politics, as you know, swirling around early missteps by the Chinese, by perhaps our own government. But if I'm reading your institute's paper correctly, that this has to go through a certain percentage of the population before it's over, then I'm wondering how serious at the end of the day, from a public health perspective, were the consequences of those early missteps? You know, if the Chinese, for example, had handled this perfectly, would we be in a fundamentally different place today than we are or not? How do you think about that?

DR. MICHAEL OSTERHOLM:

Well, you know, I've said over and over again, we're not driving this tiger, we're riding it. And what I mean by that is, is that when you have a respiratory transmitted virus like this, it clearly is a situation where what humans can do to limit transmission short of a globally available vaccine is very limited.

Now, the Chinese clearly suppressed information of what was happening in Wuhan in December of last year. And despite that, information got out. Our center began following this unfolding scenario in December, and we were able by, in the early part of January, to determine that this was not SARS or MERS, that it was acting much more like a flu virus transmission pattern – it was just generally available, public information.

On January 20th, I put out a statement that actually said that this was going to cause a pandemic globally and that transmission would occur around the world, but would not likely be detected until enough cases surfaced probably till the end of February, early March.

You know, we didn't need any classified information. We just had general source information to be able to determine that. So I don't think any other country can use as an excuse that we didn't have that information.

The Chinese really started to change course right around the first of the year and did provide much more information. Actually, on January 11th, they published the entire sequence of the virus so that any nation, any government, any private entity could begin working on a test for the virus. They could begin working on a vaccine.

In what I would call the fog of a serious outbreak or an epidemic, that was pretty fast to get that kind of information out. So I don't think that they hid any information that would have had a substantial impact on how we respond.

I think what we had was a warning at that point that we needed to gear up around the world and look at how well we were prepared to respond to a pandemic, how many N95 respirators we had, et cetera. I think, unfortunately, our government and others too squandered that time because they didn't go forward and really do the kind of preparedness work that I think most of us would do. I have a current article out in Foreign Affairs which actually goes into some detail and discusses that.

I think what did happen as I mentioned on January 20th, I came forward with a statement to this effect that it would cause a pandemic. In conversations with senior leaders at 3M, one of the largest N95 respirator manufacturers in the world, shared this information, said, you know, we really need to have all hands on deck for manufacturing these. And in fact, on the morning of January 21st, 3M went forward full bore, 24/7, full production and by more than almost six weeks beat the first request from the U.S. government for increased production.

So, you know, I think we'll go back in time and and consider who should have done what, when and where. But two points: One is this virus is going to largely do what it's going to do. And I don't believe we could ever have stopped it from transmission in our borders, even in a major way. And number two is that we did squander early time trying to get better prepared. And that's what we're hoping right now we don't continue to do in anticipating a potentially future bigger wave of this or just additional cases that will get us to that 60 to 70 percent infection level.

MICHAEL MORELL:

So, Doctor, that's actually a great transition to to another kind of thought here, which is in 2017, you wrote what I thought was a terrific book called "Deadliest Enemy: Our War Against Killer Germs," in which you outlined a strategy for addressing infectious disease threats, and what I'm wondering is, what could we have done in the years before this pandemic to have mitigated the risk of it happening and to have better prepared for it if that mitigation failed? And what should we be doing now to better mitigate and prepare for the next pandemic down the road?

DR. MICHAEL OSTERHOLM:

Well, first of all, let me say that this should never been a surprise. In fact, in 2005, I wrote pieces in Foreign Affairs and in the New England Journal of Medicine and other venues about why we weren't prepared for an influenza pandemic or a virus like an influenza that would cause this worldwide outbreak of a respiratory transmitted agent. And I must say, I wish we were back in 2005 because frankly, we were more prepared back then than we were today. And I'll point out why in a moment.

But I think the challenge we have is kind of the creative imagination to think that this can happen. You know, people such as myself have been really pretty much labeled as scaremongers, you know, as people who just, you know, 'You're scaring the hell out of us. Why?' And, you know, I've always subscribed to the idea that my job is not to scare people out of their wits but into their wits.

And I think people are now beginning to realize that in the book that you mentioned just now, in Chapter 19, there was an influenza pandemic scenario started in China in which I detailed what it would look like. And if you just take the word influenza out and corona virus in, it's exactly what's happened and unfolded, just as we said. And of course, we still have months to go.

So I think now people begin to realize that, you know, infectious diseases can do what even militaries can't do to the world, and that we now have to have a whole new respect, and understanding of what this means.

Could we have done more? Absolutely. In terms of the vaccine world, we would not have had a vaccine specifically for this virus. But how do we invest in, much like the Department of Defense does in weaponry, a whole series of different vaccine platforms through ways that we can look at this, including coronavirus? Remember, after SARS and MERS, we knew we had to be prepared for them and we still had not developed the vaccines. We've put so little resources into this that basically we could have been much, much further along in jumpstarting vaccine work.

The same thing is true with antivirals. We could have known much more, in a much more conclusive way what might work against a coronavirus. And I could lay out the other kinds of infectious agents we need to know about. So that's number one, there's no doubt about the fact that we have to prioritize how we prepare for infectious diseases.

The second thing is these are going to happen. I'm not suggesting we can stop them. But when an animal virus emerges into a human, we've got to pick it up quickly and we have to be prepared then to minimize its impact. And today, I mean, the strategic national stockpile, we have likely somewhere around 35 million in N95 respirators for the country when in fact the estimates are we'd need between 3.5 and 5 billion of them and they wouldn't materialize overnight. It wasn't like their supply chains or machines that can make them and we just didn't envision this. So we are now way behind the eight ball and protecting our basic health care workers -- that we could have done, and I could go through a list of other products like that, the testing reagents, etc.

But I think the other piece of it is, and a really very important one, is we didn't understand the vulnerability of our supply chains. For example, we've been studying for the last year and a half critical drug shortages in the United States, which are being accentuated, by the way, with this pandemic in a big way. And we brought together a world renowned group of doctors to understand what drugs are needed every day by people, what's on the crash cart, what's in the emergency room, what's in intensive care. And we came up with 156 drugs that if you don't have with an hour, people die or they're severely injured without having those drugs. One hundred percent of them are generic, 62 are already on short status, meaning that there weren't enough already in this country before the pandemic. And as generic drugs almost always remain offshore, most of them in China and India. And that vulnerability we have today not only is for the American public, but our own Department of Defense, all the critical drugs they need are coming from China.

Now, imagine if we outsource all our munitions production to China. People would say, well you can't do that. If the very basis of keeping our troops healthy or needing treatments are in the hands of these countries.

So I think that this pandemic is just accentuated all the supply chain challenges that have developed over the last ten to fifteen years and we haven't even thought about when we moved all of our manufacturing offshore and in particular to certain countries in the world. So I think that these are all things we can do in the future in a very different way. And I hope that we learn lessons from this pandemic that minimize the risk for pandemics in the future. And if they do occur, that will allow us to also limit the impact that they have.

MICHAEL MORELL:

So, Doctor, you've been terrific with your time. I just want to finish with one more question. So as I read about the virus, as a as a nonmedical person, I'm struck by how little we know. Even after four months and and more than four million confirmed cases worldwide, there is still so much that we don't know. And what I'm wondering is, as a medical expert, are you seeing about the level of knowledge that you would expect to see at this point or not? And how do you think about that question of how much we know and how much and how long it's going to take for us to know that?

DR. MICHAEL OSTERM

Well, we do have a lot yet to learn. One is just about the disease itself. As I mentioned earlier, we're learning a lot about the many facets of the disease picture. It's not just a simple, straightforward disease. We are learning more about the virus all the time. And, you know, What made it get to this point? It does what it does. We're learning about how it's changing as it transmits around the world.

I think the level of new knowledge and information is overwhelming right now. I've never seen a proliferation of scientific information so quickly. The international response for vaccine research and looking at how vaccines might work here, looking at drugs, again, is unprecedented. I think our country and our government has done a lot to fast fastforward that.

So I do think that almost all the things that we need, we are getting done in terms of information. The challenge is, again, we're on virus time, not human time. And what we need are answers yesterday, not tomorrow. We will get answers. But I think the challenge we have is understanding, for example, certain drugs are going to work. Why would they work based on what we know about the disease? Well, we are learning things about this disease literally within the last week that we didn't know a month ago.

So I think that it's just the fact that we're digesting lots and lots of information quickly. But I I'm impressed by the body of knowledge. And if anybody is trying to stay current in this field, it is a real challenge given the number of publications and the number of different studies that are coming forward every day.

MICHAEL MORELL:

Doctor, thank you. Thanks so much for joining us. I want to tell my listeners that they should look for your Foreign Affairs article out this week and they should also spend some time on your institute's website. I do several times a week and I find it incredibly useful. So, again, thank you for joining us. And it was great to have you.

DR. MICHAEL OSTERHOLM:

Thank you very much. It's my honor. Appreciate it.