Denver mayor's proposal for pallet homes is similar to the one Aurora put in place recently

Denver leaders are considering 11 different sites for micro communities in each of the Mile High City's 11 districts in a plan that's similar to Aurora's. Denver plans to buy 200 pallet shelters. The sites will be vetted in the coming weeks to help meet Mayor Mike Johnston's goal of getting 1,000 people off the streets by Christmas.

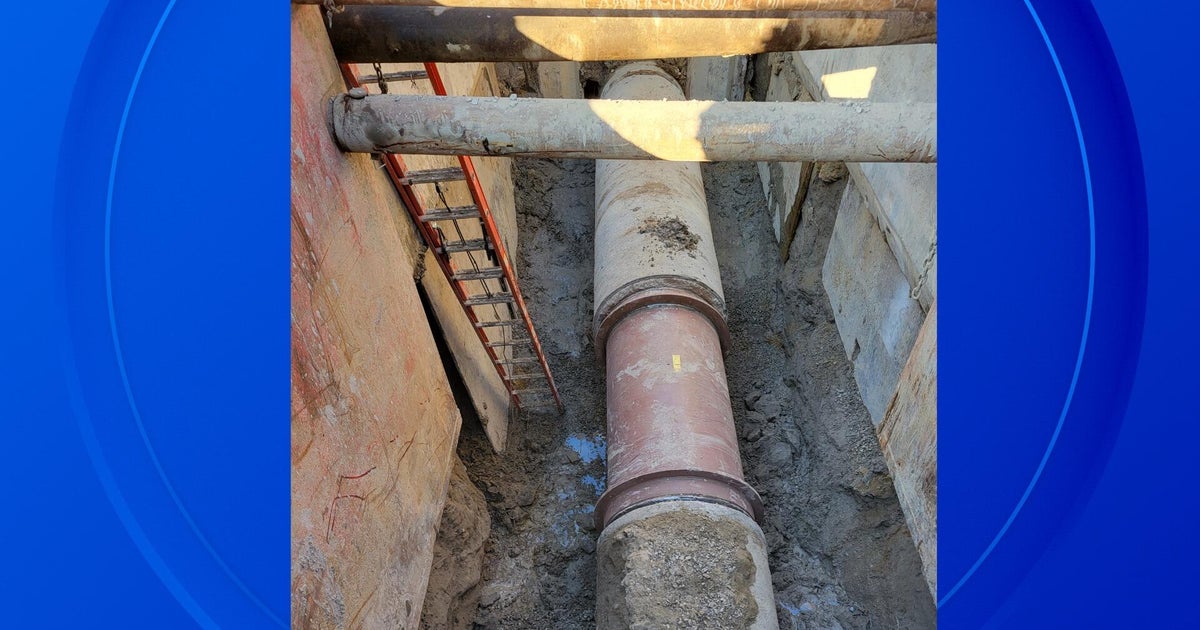

Aurora has been using pallet shelter villages for a year and a half to assist the homeless. There are rows of them -- about 40 total -- outside the Salvation Army's warehouse in an industrial area near East 33rd Avenue and Peoria Avenue. It's a small community on the hard pavement of the parking lot.

"People here are decent. The staff is just -- you can't say nothing bad about them, they're just wonderful people," said CJ Gogerty, who was cleaning up when a CBS Colorado news crew visited on Thursday.

Gogerty first ended up homeless in 2020 after losing his job among medical problems. He still wears a mask due to a weak immune system.

"I'm a native and this is where I'm at," he shared.

He spent the early part of his life growing up in Boulder County and working to support himself until things turned.

"Housing in Colorado is too expensive. Pretty much living in Colorado is too expensive," he said.

Johnston announced his plans for 11 pallet home communities on Thursday. He says they are a first step off the streets.

For the past 6 months, Gogerty has been living in the community of Aurora's pallet homes. Each is 10 x 10, equipped with power, air conditioning and heat. Group bathrooms are down the way with outdoor sinks. There is a shower trailer. The Salvation Army keeps staff on site 24 hours a day.

"The only requirement that we have is that folks meet our community expectations or community agreements," explained the program manager of the Salvation Army's Safe Outdoor Spaces, Callie Craig. "It's a basic set of rules. We do consider ourselves a low barrier shelter."

Sobriety is not a requirement but drugs and alcohol are not allowed on site. People meet weekly with a caseworker. Many stay for one month, a program put in place after Aurora initiated a camping ban. Others stay for six months.

"Often times we see this as a starting point because it is very accessible for most," said Craig.

"We are trying to show them community and we are trying to show them that they don't have to go back to the streets."

Craig says they have learned some things since starting the pallet village where a tent community was allowed a year and a half ago. They need to ensure staff are not burning out as well.

"We see what works for our staff , for our guests and what doesn't work."

The existence of wraparound services is important.

"We are working on more community partners as we go. We refer people out to other organizations for things like mental health and things like sobriety access resources."

But more mental health help is always in demand.

"It's often a matrix of traumas and things that have happened in a person's life that have led them to this point. Nobody is out here by choice. And I firmly believe that," said Craig.

Sarah Alvarado, who is called Luna by just about everyone around, arrived only three weeks ago. There is already a housing voucher waiting for her. She is getting a job with the Salvation Army and hopeful. But outside her tiny pallet home is still a pile of belongings that don't fit. She is still worried that she might need them if she ends up back on the streets.

"It's not an easy thing every day still living out here wondering if we're going to be put back out there," said Alvarado.

"I feel more safe here than I have in three years," said Alvarado referring to the three years she spent without a home.

But she knows there is not enough of this kind of transitional housing and is concerned for the friends she left behind on the streets.

"They're waiting, too. They need their chance too. It's not just us."