Indian boarding school trauma recalled by Denver elder as state launches study

The State of Colorado is launching an investigation into the history of Indian boarding schools.

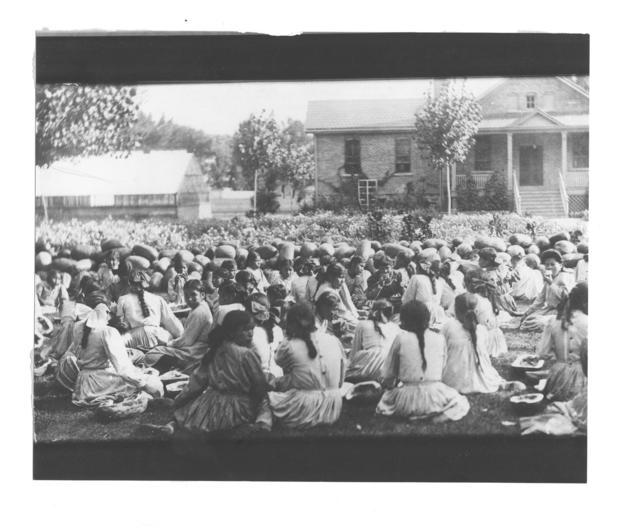

For more than 100 years many Native American children were separated from their families and forced to attend government or church-operated boarding schools.

History Colorado will lead the study, focusing on the federal Indian boarding school in Hesperus, Colorado. It will also identify potential burial sites for students who died while attending school there. The Native American Boarding School Research Program Act, HB22-1327, was signed into law by Governor Jared Polis on May 24, 2022.

Metro Denver is home to descendants of some 200 tribes, many of whom came here following the Urban Relocation program of the 1950s and 1960s. Current students at the American Indian Academy of Denver (AIAD) are among those whose families were affected by the boarding school and relocation practices.

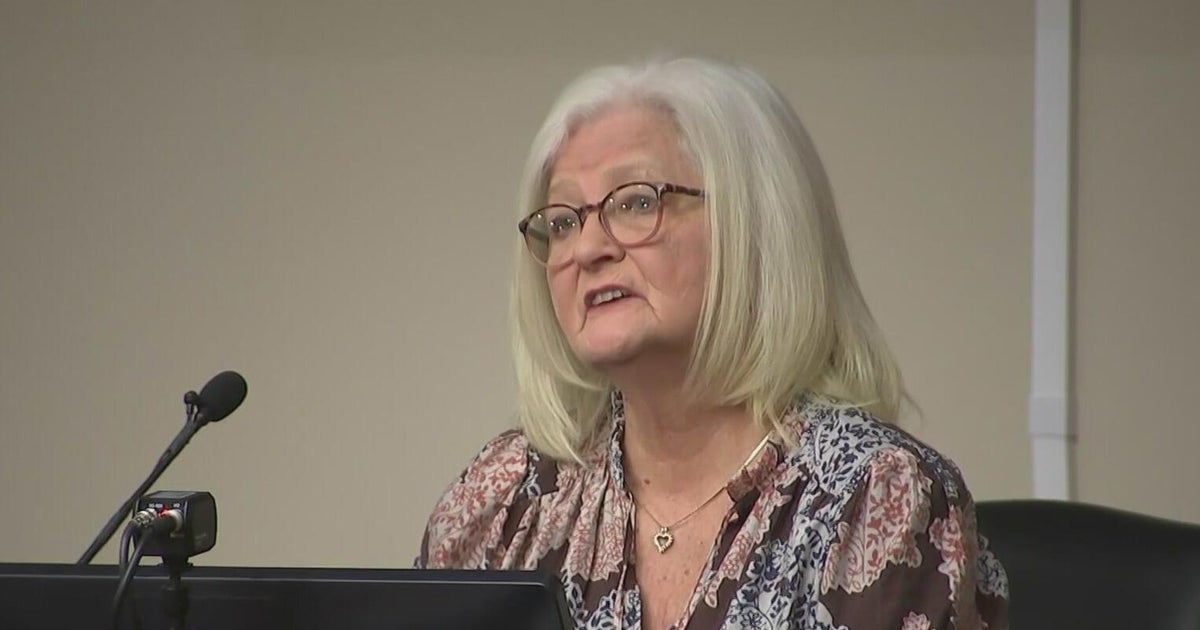

Terri Bissonette is Founder and Head of School at AIAD, and said, "The education systems in the United States were literally set up to destroy us, it was an explicit intent. To kill the Indian and save the man."

Bissonette's mother Silvia Chingwa has lived in Denver since the 1960s. In 1946 at the age of six she was separated from her Odawa family in Michigan, taken to the Holy Childhood boarding school in that state - an effort driven by the federal government.

"All I know is I was terrified," Chingwa said. "There was this person standing there with a black outfit and not very friendly. All of our native stuff that they took from us at the beginning of the school year, they threw it and they burnt it up."

Chingwa was studious and said she tried to be a good Catholic Indian kid. But her aspirations were dampened by what her boarding school teachers told her, recalling, "'You're just a dirty little Indian kid, why would you want to go to college? Who's going to accept you?'"

Chingwa went on to obtain multiple degrees and today is an elder volunteer at AIAD, where her daughter Terri is the founding principal. Educators at AIAD believe reclaiming history is essential to preparing students for the future.

They say Colorado's effort to uncover the boarding schools' mission to strip native people of their culture is long overdue. Bissonette said, "To eradicate our languages, to eradicate our belief systems to make us be someone that we were not."

Chingwa's younger brother Vernon died of diphtheria while at the boarding school. She said, "The nun leaned over and said, 'oh by the way your brother died last night.'"

Bisonnette added, "In addition to their own trauma that they're experiencing she also had to take on that responsibility that she was supposed to be watching out for Vernon and she couldn't. And so those types of things when it's not resolved, it just perpetuates and we see it in our communities."

The intent of the study is to develop recommendations to support healing in tribal communities.

"It's been quietly swept under the rug and so it's really important, it's really important for this history to be told and to be understood," Bissonette said, "And it's ironic that education is now the thing that's gonna save us."

History Colorado will provide an update on its study this Thursday September 8th to the Colorado Commission on Indian Affairs, the Southern Ute Indian Tribe and the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe. The agenda and Zoom information can be found here .