Burden On Prosecutors To Prove Sanity In Holmes Case

DENVER (AP) - If James Holmes pleads not guilty by reason of insanity, prosecutors wanting to prove that he methodically carried out a deadly Colorado movie theater shooting have a difficult task before them: They must prove he is sane.

Unlike other states where the defense needs to prove insanity, prosecutors in Colorado are the ones who have to show that a defendant is sane — all without the ability of having their own experts examine Holmes.

"It's burden of proof on steroids," said Marcellus McRae, a former federal prosecutor now in private trial attorney in Los Angeles. "It's totally subjective. It's not like proving somebody pulled the trigger. That's objective."

Whether he pleads guilty by reason of insanity, the case against Holmes promises to focus on his mental health.

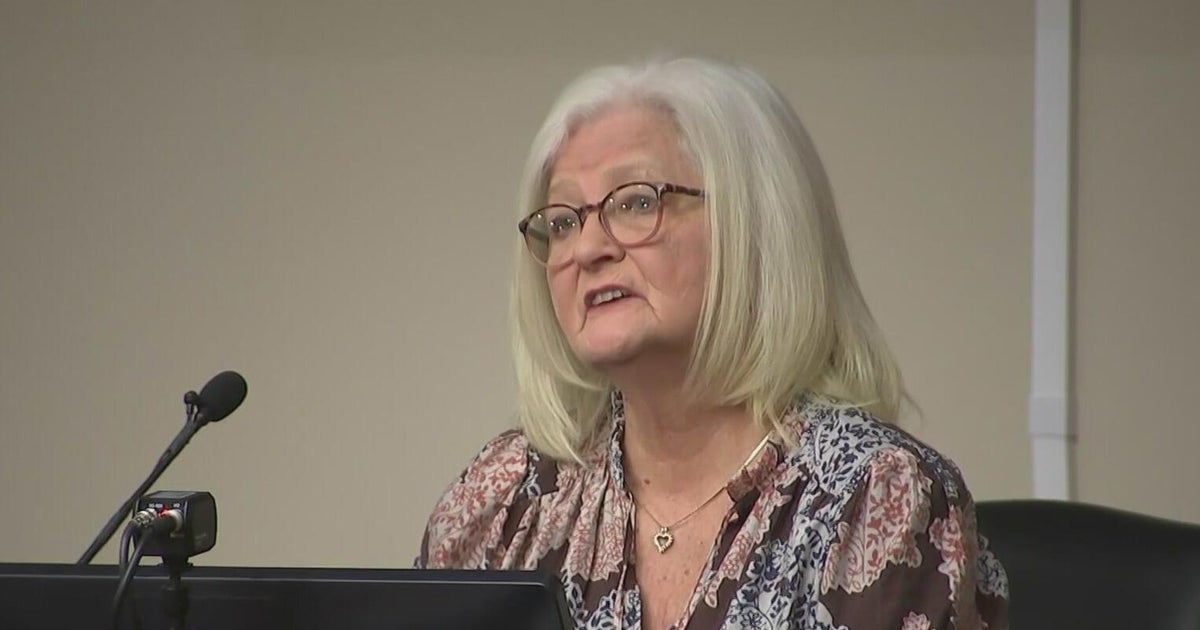

A court hearing Thursday will examine his relationship with University of Colorado psychiatrist Lynne Fenton, to whom he mailed a package containing a notebook that reportedly contains violent descriptions of an attack.

His attorneys say Holmes is mentally ill and that he sought help from Fenton at the school, where he was a Ph.D. student, until shortly before the July 20 shooting that killed 12 people and wounded 58 others. Prosecutors allege that Holmes may have been angry at the failure of a once promising academic career.

Insanity is unlike the mental competency argument used for Jared Loughner, who ultimately pleaded guilty in federal court to the 2011 Arizona shooting that killed six people and wounded 13 others, including then-Rep. Gabrielle Giffords.

Mental competency involves whether a defendant is aware of what's happening in court and can assist his or her attorneys with a defense. In Loughner's case, he received treatment, became competent and entered his plea.

In an insanity defense, a defendant is deemed not guilty because he didn't know right from wrong and is therefore "absolved" of the crime, Jefferson County District Attorney Scott Storey said, who recently lost an insanity case.

If Holmes is found sane and goes to trial and is convicted, his attorneys can try to stave off a possible death penalty by arguing he is mentally ill. Prosecutors have yet to decide whether to seek the death penalty.

Authorities have said that Holmes meticulously stockpiled ammunition and other gear and booby-trapped his apartment to kill, suggesting that he knew what he was doing.

With the burden on prosecutors, those details don't matter, prosecutors say.

Insanity cases depend on a court ordered evaluation by state psychiatrists and up to two additional state evaluations requested by defense attorneys or prosecutors and approved by a judge.

In about 40 states and in federal court, the burden of proof is on the defense, which must prove that a client is insane.

Two recent cases illustrate their difficult task.

In October, Bruco Strong Eagle Eastwood was acquitted by reason of insanity of attempted first-degree murder in the wounding of two children outside a Colorado school, a case that garnered national headlines after a math teacher tackled him and stopped the shooting. Eastwood is spending time in a mental hospital.

His case will be reviewed every six months until he's deemed sane and released.

Storey, the prosecutor, said the average stay in a state hospital for homicide is 7.5 years.

Storey had Dr. Steven Pitt, known for his work on the Columbine shooting, examine Eastwood's mental health records and interview witnesses — but by law, Pitt could not interview Eastwood.

At trial, Pitt testified he could not say Eastwood was sane at the time of the shooting because he could not see him.

Two court-appointed state doctors did find Eastwood, previously diagnosed with schizophrenia, insane, even though Eastwood had visited the school hours before the shooting, waited for a school resource officer to leave and acknowledged in questioning after his arrest that he knew what he did was wrong.

Asked what he was thinking during the shooting, Eastwood told investigators: "Accuracy."

Storey attributed Eastwood's acquittal to Pitt's inability to examine Eastwood. "I think it's a flaw in the statute that needs to be corrected," he said.

In Boulder County, District Attorney Stan Garnett is appealing a judge's decision not to allow a prosecution expert to examine Stephanie Rochester, who suffocated her 6-month-old son in 2010 because she said she feared he had autism.

A state psychiatrist determined that Rochester had a major depressive disorder, and the judge declared her not guilty by reason of insanity in January.

"You need to make sure that both sides have equal access to the same information, which in a sanity case is the opportunity to examine the defendant," said Garnett, who cited evidence that Rochester tried to suffocate her baby over several hours, returning to the dinner table with her husband after an unsuccessful attempt.

In his appeal, Garnett isn't seeking a retrial of Rochester but an opinion to clarify the law for judges in future cases.

"Because the defendant is the sole source of evidence in this situation, courts have noted a defendant's opportunity to manipulate the information the prosecution receives," Garnett argued in his appeal.

Defense attorneys say the system is fine because a defendant gives up certain rights when pleading insanity, including the right to remain silent. Once a defendant enters his plea, the court orders an independent evaluation by a state doctor, from whom findings of insanity in criminal cases are rare, said Scott Robinson, a Denver criminal attorney.

"It's not an 'our doctor, your doctor' thing," Robinson said. "There is a certain built-in advantage for the defense, but only if the opinion from the state evaluation is insanity."

"What they're saying is, 'When we don't like what the independent state-hired psychiatrist finds, we want to be able to get our own hired guns and find somebody to say that he is not insane,'" said Denver criminal defense attorney Dan Recht, a former public defender and past president of the Colorado Criminal Defense Bar. "The constitution says, 'Sorry, you don't get that in this case or any other case.'"

In federal court, a defendant has to prove by clear and convincing evidence that he is insane.

John Hinckley Jr.'s acquittal by reason of insanity in his 1981 assassination attempt on President Ronald Reagan prompted the federal government and dozens of states to change their laws to shift the burden of proof of insanity to defendants.

The uphill battle for prosecutors is compounded by the incomprehensible nature of the crime.

"What do you think the popular mindset is about somebody coming into a theater and killing a bunch of people? That he's crazy," McRae, the former federal prosecutor said. "If they (prosecutors) didn't have to prove insanity this wouldn't be much of a trial at all."

By P. SOLOMON BANDA, Associated Press

(© Copyright 2012 The Associated Press. All Rights Reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.)