Emergency planners in Colorado county discuss procedures for school evacuations in major fires

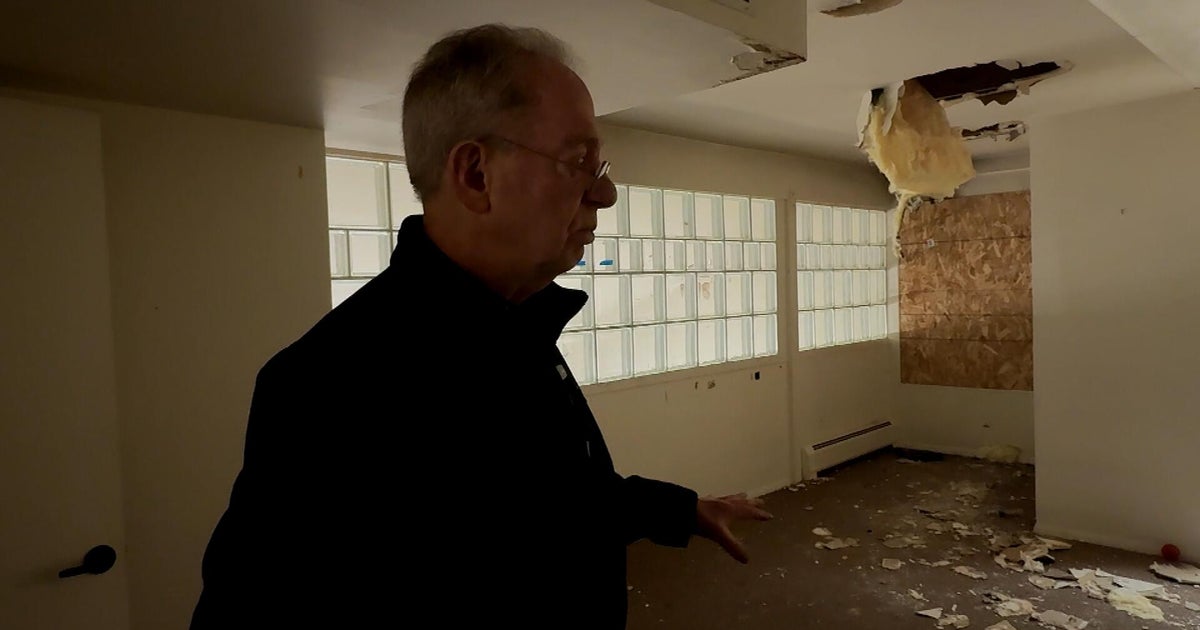

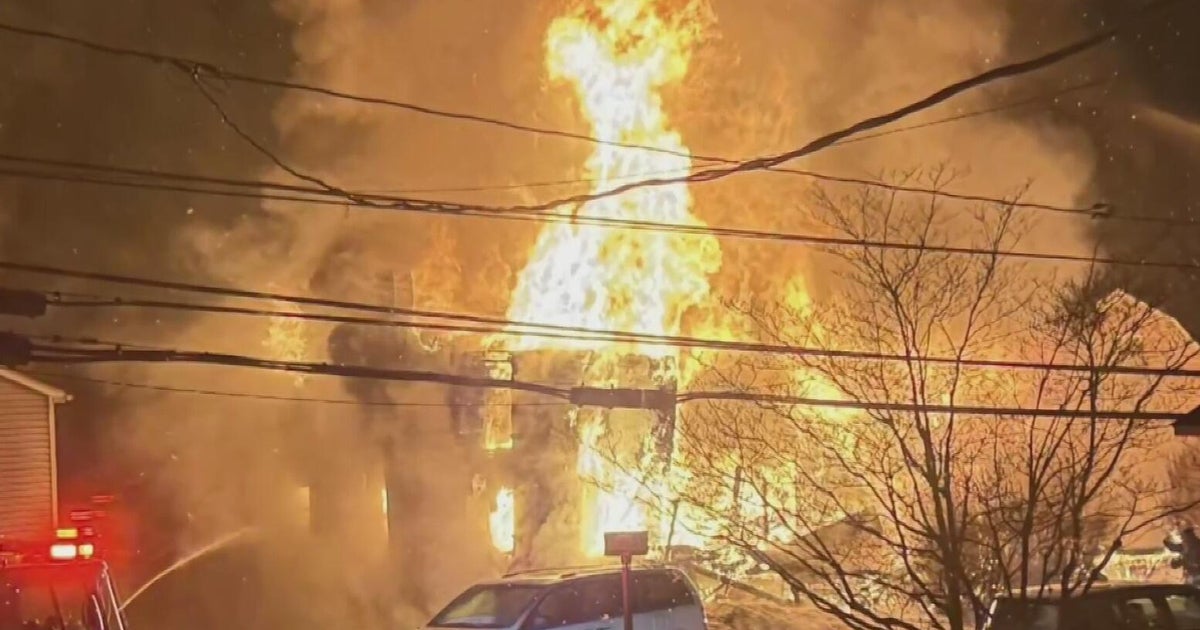

In the two and a half years since the Marshall Fire destroyed over 1,000 homes in Boulder County, there have been reviews and thoughts about what could have been done better. And there are some who have thought what if things had been worse?

A big question: What if schools had been in session? The wildfire that hit on Dec. 30, 2021 blew wind-whipped flames across vast portions of Superior and Louisville as well as Marshall and portions of unincorporated southern Boulder County.

"The Marshall Fire was a massive event, and it really gave us an opportunity to look at where our weaknesses were, look at where we had opportunities to make significant changes in our safety posture," said Brendan Sullivan, director of Safety, Security and Emergency Management with the Boulder Valley School District.

The school district got very lucky. Not only were children home on winter break, but no schools were hit.

"All the children were home at the time of the fire. But the thought that everyone had immediately after the fire was what if that happened when schools were in?" said Tawnya Somauroo, a parent of two children heading into first grade this year.

Somauroo has been part of the Marshall Fire Together organization that has advocated for fire victims after her family's home burned. She and her husband and children are now back in their rebuilt home in Louisville and thinking about some of the what-ifs after suffering through the trauma of the fire.

"Parents had this experience when we were in our car with our terrified children, trying to get out of here. Stuck in traffic, seeing smoke and flames. It was terrifying," Somauroo said.

District officials in Boulder County have been meeting with law enforcement and fire officials to plan how to handle fires. On Monday night, they went to the Board of Trustees in Superior to share planning information. But the district is not alone in the need of preparing for mass school evacuations.

"Developing early warning systems for us. Making sure red flag days that we have extra awareness. That we take extra inventory of our schools," cited Sullivan, ticking off a list of things to consider.

Buses that would be needed are likely offsite from schools, and drivers might not be available. School leaders, Sullivan noted, need to be thinking about those issues, especially on high risk days.

"See who's available. How many buses do we have? How long would it take to get them?" Sullivan said. "All of those different considerations if we need to act quickly, We're not trying to develop a game plan at the time. We're just ready to roll."

Bus drivers and buses could be going to schools against the flow of evacuating traffic. That makes for traffic nightmares if local law enforcement isn't ready to let them through.

Parents will need a degree of trust to think that school districts are capable of taking care of their children at times of evacuation. It's all part of a complicated formula for dealing with emergencies that are hard to envision.

"I think you make the best plans that you can, and you have to communicate them to parents because, if parents don't know what to expect, they're going to panic, and they're all going to try to drive towards the school," Somauroo said.