Hidden in Plain Sight: How kinkofa is preserving Dallas' Black history

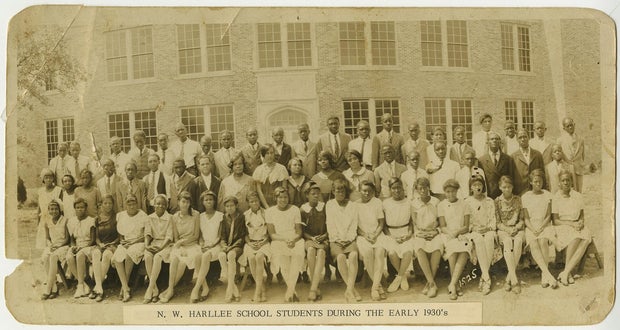

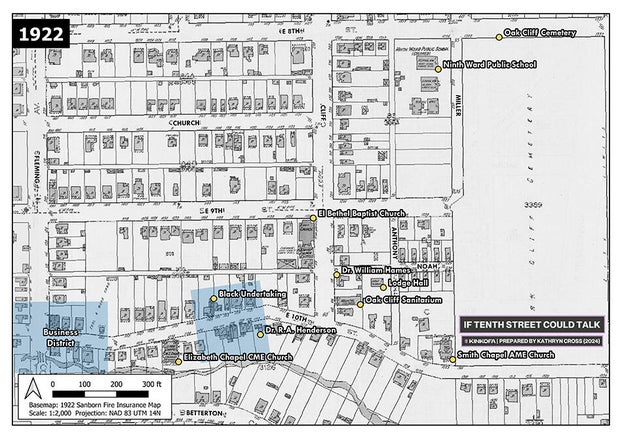

Nestled in the heart of Oak Cliff, just south of downtown Dallas, the Tenth Street Historic District is one of the only remaining intact Freedmen's Towns in the country.

Founded during the post-Civil War era by formerly enslaved people seeking refuge from racial violence in the South, the community grew into a self-sustaining neighborhood.

A Freedmen's Town is considered intact when it retains its original architecture, such as homes and buildings, along with key institutions like a church, school and cemetery.

"Tenth Street is pretty unique," said Meshia Rudd-Ridge, co-founder of kinkofa, a digital platform dedicated to preserving Black family histories. "It's both a Dallas landmark district, and it's on the National Register of Historic Places."

One significant part of this history is the Oak Cliff Cemetery. Dating back to the 1830s, the cemetery is considered the oldest public cemetery in Dallas County. It holds the history of some of the earliest Black landowners and civic leaders.

"It has historically been a segregated cemetery," Meshia said. "There's this line of demarcation where there's these big elaborate headstones at the front. As you're going towards the back, it's like, 'Wait, is this land to bury more people or are there people here?' The white side of the cemetery, there's plots and they're labeled and outlined. Then the Black part of it just said 'African American section.'"

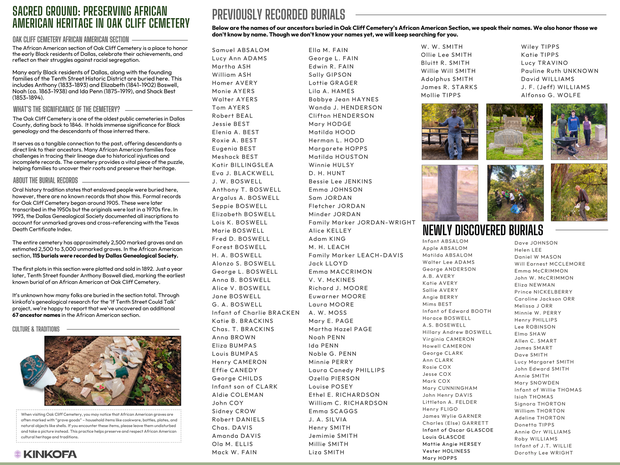

This is where kinkofa plays a key role. Using historical records, such as public cemetery and land records, personal family archives, and oral histories, the organization focuses on identifying unmarked graves in the cemetery's African American section.

"So far we have 100 plus and growing," Meshia said. "There are 116 that were documented on the cemetery records, and we found 103 that are not so far. We're still definitely not through all of the records yet for the African American section."

The Process

Meshia and her fellow co-founder, Jourdan Brunson, who is a genealogist, describe themselves as many things: memory workers, creative technologists, and family and community historians.

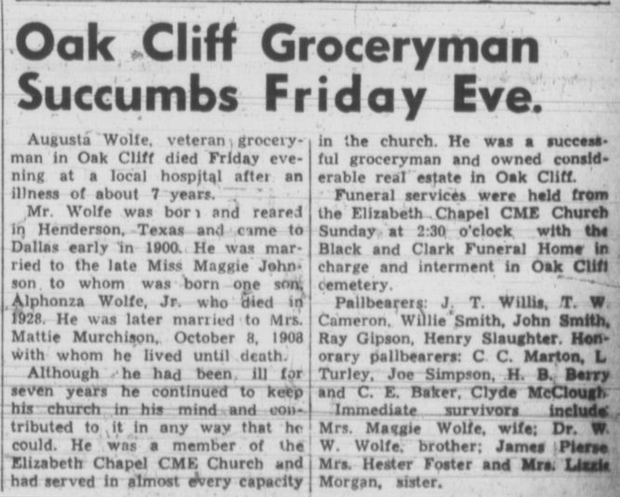

"We may start with a story or a name that we get from somewhere," Jourdan said. "From there, I might want to find that person's name in records like the Census or birth, marriage, and death records, to learn more about their family and where they lived."

One place they often find a name or story is in the newspaper. The duo cites both The Dallas Express and The Dallas Morning News as crucial sources for stitching together a clearer picture of life in the community 100 years ago, comparing announcements in the papers to social media posts.

"You can see who was hosting a party that week, or what was happening at church, who was sick, who had a funeral, who was born," Meshia said.

Another vital source for kinkofa is oral histories, which they say is how Black communities often document their stories.

"Oral history is just the way a lot of Black folks get started," Jourdan said. "Sometimes we're family historians or community historians without even realizing it. And sometimes it might be all we have, just telling and keeping those stories alive."

The Cemetery

Between the 1940s and early 1950s, the cemetery fell into a state of disrepair, which may explain why there are so many unmarked graves on the grounds.

"Some folks, they might've had headstones at one point," Meshia said. "Some of them might be buried under the earth, and we don't even know."

At the cemetery, we met with archaeologist and Remembering Black Dallas volunteer Dr. Katie Cross, who is helping organize cemetery cleanups, mapping the cemetery, and coordinating with other archaeologists to do ground-penetrating radar (GPR) surveys.

"Ground-penetrating radar looks for anomalies under the surface," Dr. Cross said. "It's a noninvasive technique used to look for unmarked graves. Because of the way you dig a grave, where you take out the soil and then you put it back, it comes up looking differently than the dirt around it."

In addition to GPR, Dr. Cross said the team will also use drones and mapping techniques. This combination will help build a better picture of the layout of the African American section, allowing for the best guess at where unmarked graves might be located.

"Even if we don't know who those people are," Dr. Cross said. "We at least know where people are. Even though we may not be able to match some of the death records Meshia and Jourdan have found with an unmarked grave, we can still commemorate those people in some way."

One part of kinkofa's project is the potential creation of a wall of names along the back side of the cemetery at 10th Street and Clarendon Street. This wall would offer a space to honor and see the names of ancestors, even if specific headstones cannot be pinpointed.

The Challenges

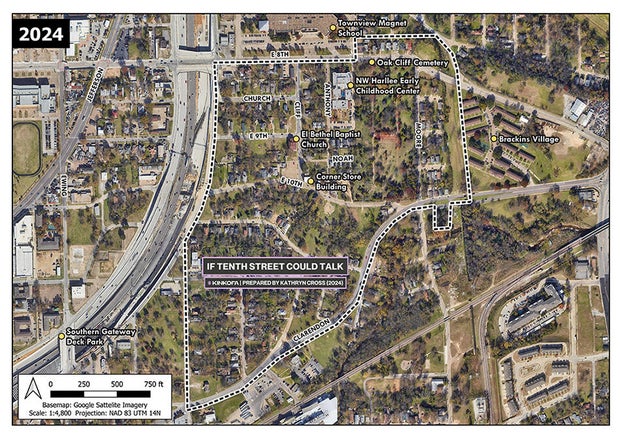

One of the biggest hurdles for the cemetery project is the cleanup. The cemetery, and the community as a whole, have suffered from neglect, illegal dumping, and encroaching urban development. Most significantly, I-35, built in 1959, cut the west side of the neighborhood, resulting in the demolition of more than 100 homes and businesses. The stark contrast is demonstrated in kinkofa's first project in 2024, "If Tenth Street Could Talk."

In 2023, Dallas began construction on Halperin Park between Ewing and Marsalis, which is aimed at reconnecting the community that was severed by the highway. Phase one is slated to open in early 2026.

"It's been made clear this area is a thoroughfare," Meshia said. "Now anybody is just coming through here and they're like, 'This place looks like a dump, I'll throw my trash everywhere.' But I want people to know this place isn't a dump. I'm almost completely disheveled when I pull up and there's a lot of trash here. Seeing headstones broken and toppled over, trees and branches everywhere—I have mixed emotions."

The challenge is not just cleaning up the space, but reclaiming the memories and legacy of those whose lives were displaced and forgotten.

"There's a lack of record keeping," Meshia said. "A lot of people were forced out of their homes over time. The construction of the highway and other racial inequities pushed people away from their homes, so they lost things."

The cemetery's neglect represents the community's fight to preserve its identity amidst ongoing systemic forces.

"From when Tenth Street was founded through when the highway was built, it was the city neglected," Dr. Cross said. "They refused to see the significance of these places and I feel like that still carries over today. It leads to this forgetting by our city, not by the people who know about it, but by the broader public."

Preservation & Education

With no library or museum in the community, Meshia referred to Tenth Street as a "real-life museum," emphasizing how the neighborhood itself is a living testament to the area's rich history and the critical importance of educating people about its legacy.

"A lot of folks don't know they're descendants from here or why this place is important," Jourdan said. "Without education, communities like Tenth Street no longer exist, so it's important to preserve the history of Tenth Street and Tenth Street as it is today."

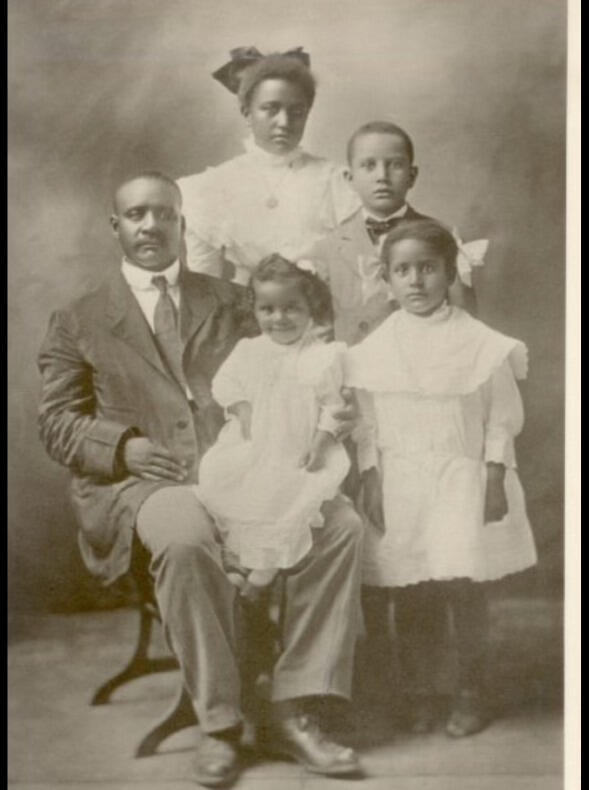

Standing next to Anthony Boswell's family plot, Meshia shared how he is known as the founder of Tenth Street-after purchasing the first lots of what would eventually form the heart of this vibrant community. He was joined by his brother Hillary Boswell and Noah Penn, two other notable figures in the area's early development. This is only the beginning of many untold stories that reside within the cemetery grounds.

"There's an interest in discovering Black history," Jourdan said. "And Tenth Street is a hub of Black history for Dallas and for the world."

One way to explore and learn more about Dallas' Black history is through kinkofa's newly launched Black History Map. Utilizing AI technology and the data they've gathered, the interactive map allows users to uncover stories about Black history across the country while also offering a platform to contribute their own personal histories.

How to Get Involved

The story of Tenth Street is one of resilience, reclamation, and the ongoing fight to preserve a community's history in the face of systemic erasure. As kinkofa continues its work to document, preserve, and honor the memories of those laid to rest in Oak Cliff Cemetery, they want to emphasize that this work requires help from everyone.

"It's going to take all of us for our history to be preserved," Meshia said. "This is everybody's history, it's not just Black people's history. We're not going to exist in the future if we're not working together."

Educating yourself is one way that kinkofa said you can start getting involved. They also suggest listening to the community about their vision for Tenth Street. Donations are also accepted—whether that's time, money, or skills. To learn more about how to get involved, preservation efforts, and Black history, visit kinkofa or Remembering Black Dallas.