From Texas Private School Student To al-Qaida Agent

(AP) - Moeed Abdul Salam didn't descend into radical Islam for lack of other options. He grew up in a well-off Texas household, attended a pricey boarding school and graduated from one of the state's most respected universities.

But the most unlikely thing about his recruitment was his family: Two generations had spent years promoting interfaith harmony and combating Muslim stereotypes in their hometown and even on national television.

Salam rejected his relatives' moderate faith and comfortable life, choosing instead a path that led him to work for al-Qaida. His odyssey ended late last year in a middle-of-the-night explosion in Pakistan. The 37-year-old father of four was dead after paramilitary troops stormed his apartment.

Officers said Salam committed suicide with a grenade. An Islamic media group said the troops killed him.

Salam's Nov. 19 death went largely unnoticed in the U.S. and rated only limited attention in Pakistan. But the circumstances threatened to overshadow the work of an American family devoted to religious understanding. And his mysterious evolution presented a reminder of the attraction Pakistan still holds for Islamic militants, especially well-educated Westerners whose Internet and language skills make them useful converts for jihad.

"There are things that we don't want to happen but we have to accept, things that we don't want to know but we have to learn, and a loved one we can't live without but have to let go," Salam's mother, Hasna Shaheen Salam, wrote last month on her Facebook page.

The violence didn't stop after Salam died. Weeks after his death, fellow militants killed three soldiers with a roadside bomb to avenge the raid.

It is not clear to what extent Salam's family knew of his radicalism, but on his Facebook page the month before he died, he posted an image of Anwar al-Awalki, the American al-Qaida leader who was killed in a U.S. drone strike in Yemen, beside a burning American flag. He had also recently linked to a document praising al-Awalki's martyrdom and to a message urging Muslims to rejoice "in this time when you see the mujahideen all over the world victorious."

After his death, the Global Islamic Media Forum, a propaganda group for al-Qaida and its allies, hailed Salam as a martyr, explaining in an online posting that he had overseen a unit that produced propaganda in Urdu and other South Asian languages.

A senior U.S. counterterrorism official said Salam's role had expanded over the years beyond propaganda to being an operative. The official spoke on condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the information.

The family, originally from Pakistan, immigrated to the U.S. decades ago. Salam's father was a pilot for a Saudi airline, and the family eventually settled in the Dallas suburb of Plano. Their cream-colored brick home, assessed at nearly $400,000, stands on a corner lot in a quiet, upper-class neighborhood.

The family obtained American citizenship in 1986. Salam attended Suffield Academy in Connecticut, a private high school where tuition and board currently run $46,500. He graduated in 1992.

A classmate, Wadiya Wynn, of Laurel, Md., recalled that Salam played varsity golf, sang in an a cappella group and in the chamber choir, and that he hung out with a small group of "hippie-ish" friends. She thought he was a mediocre student, but noted that just being admitted to Suffield was highly competitive.

Salam went on to study history at the University of Texas at Austin and graduated in 1996. His Facebook profile indicated he moved to Saudi Arabia by 2003 and began working as a translator, writer and editor for websites about Islam.

"Anyone can pick up a gun, but there aren't as many people who can code html and understand the use of proxies," said Evan Kohlmann, a senior partner a Flashpoint Global Partners, which tracks radical Muslim propaganda.

Salam, who had apparently been active in militant circles for as long as nine years, arrived three years ago in Karachi, Pakistan's largest city, and became an important link between al-Qaida, the Taliban and other extremists groups, according to an al-Qaida operative in Karachi who spoke on condition of anonymity because he is wanted by authorities.

Salam traveled to the tribal areas close to the Afghan border three or four times for meetings with senior al-Qaida and Taliban leaders, the operative said. He would handle money and logistics in the city and deliver instructions from other members of the network.

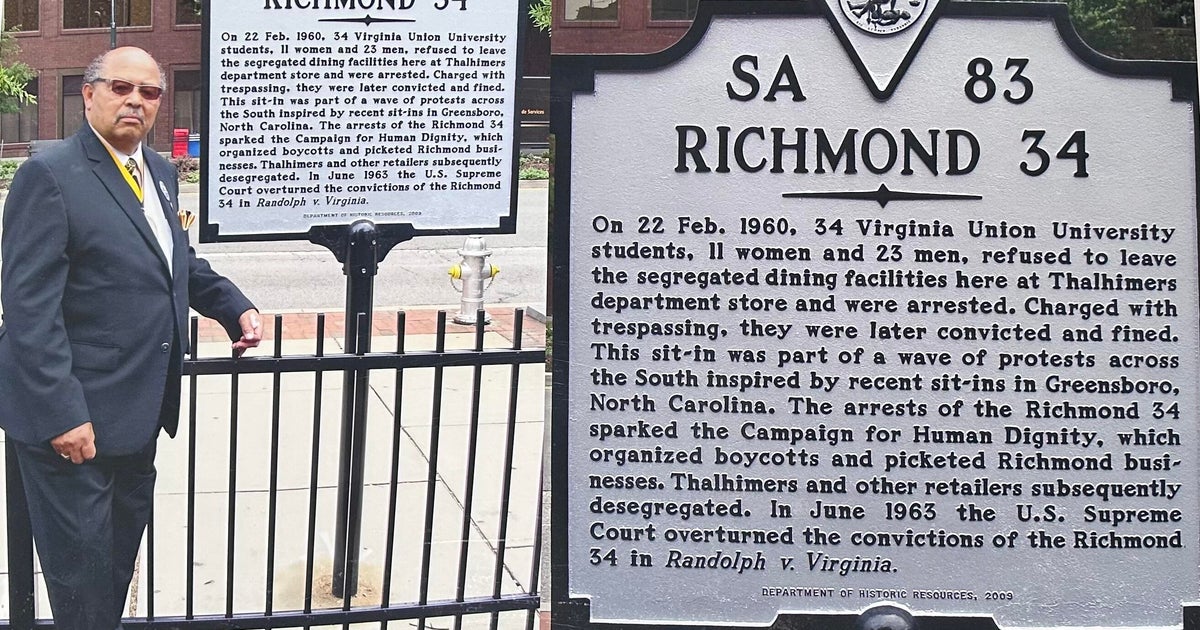

Back in the United States, Salam's mother is a prominent resident of Plano, where she is co-chairwoman of a city advisory group called the Plano Multicultural Outreach Roundtable, as well as a former president of the Texas Muslim Women's Foundation.

The founder of the latter group, Hind Jarrah, said Shaheen and her husband are too upset to speak with anyone.

"She's a committed American citizen. She's a hard worker," Jarrah said, calling her "one of the nicest, most committed, most open-minded" women she had ever met.

Salam's brother, Monem Salam, has traveled the country speaking about Islam, seeking to correct misconceptions following the 9/11 attacks. He works for Saturna Capital, where he manages funds that invest according to Islamic principles -- for example, in companies that do not profit from alcohol or pork. He recently moved from the company's Bellingham, Wash., headquarters to head its office in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

After the 2001 attacks, he and his wife made a public-television documentary about his efforts as a Muslim man to obtain a pilot's license. They also wrote a column for The Bellingham Herald newspaper that answered readers' questions about Islam.

Both Salam's parents and his brother declined numerous interview requests from The Associated Press.

Since the 2001 terrorist attacks, dozens of U.S. citizens have been accused of participating in terrorism activities, including several prominent al-Qaida propagandists, such as al-Awalaki and Samir Khan, who was killed alongside him. Perhaps best known is Adam Gadahn, an al-Qaida spokesman believed to be in Pakistan.

Of 46 cases of "homegrown terrorism" in the U.S. since 2001, 16 have a connection to Pakistan, according to a recent RAND Corporation study. Salam's background as college-educated and from a prosperous family isn't unusual among them.

Salam divorced his wife in October, but was contesting custody of their three sons and one daughter. The children were staying with him in the third-floor apartment when a squad of paramilitary troops known as Rangers arrived around 3:30 a.m.

Officers said they pushed through the flimsy door, and Salam killed himself with a grenade when he realized he was surrounded.

The Islamic media group and the al-Qaida contact in Karachi disputed that account, saying Salam was killed by the troops.

Through the windows, blood splatter and shrapnel marks were visible on the wall close to the dining table. There were boxes of unpacked luggage, a treadmill and two large stereo speakers. Residents said Moeed had only been living there for five days.

Neighbor Syed Mohammad Farooq was woken by an explosion. Minutes later, one of the troops asked him to go inside the apartment and see what had happened, he said.

"He was lying on the floor with blood pooling around him. One of his arms had been blown off. I couldn't look for long. He was moaning and seemed to be reciting verses from the Koran," he said. "I could hear the children crying, but I couldn't see them."

Hours later, Salam's wife and father-in-law, a lawyer in the city, came to collect the children from the apartment in Gulistane Jauhar, a middle-class area of Karachi, Farooq said. On the night he died, Salam led evening prayers at the small mosque on the ground floor of the apartment building.

"His Koranic recitation was very good," said Karim Baloch, who prayed behind him that night. "It was like that of an Arab."

(© Copyright 2012 The Associated Press. All Rights Reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.)