Your Alexa And Fitbit Can Testify Against You In Court

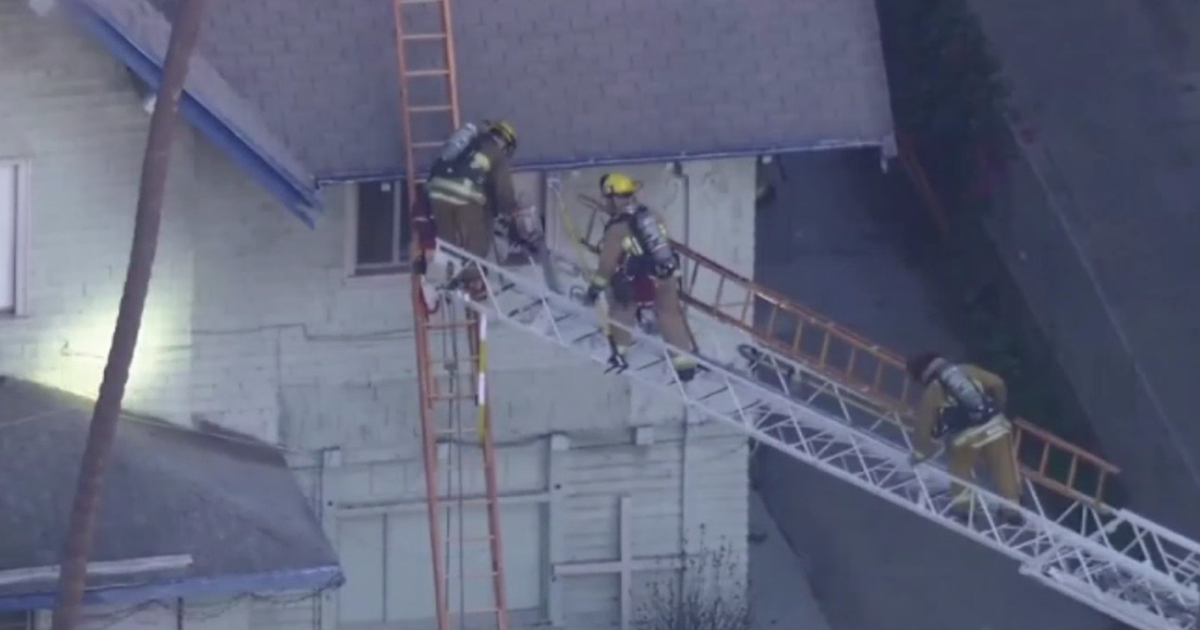

NEW YORK (CNET.COM) - Ross Compton had no idea his pacemaker would finger him for arson.

Compton — who also needs an external heart pump — told police he was asleep when his Middletown, Ohio, home caught fire in September 2016. As the flames licked the 2,000-square-foot house, he packed a suitcase with some clothes, stashed other items into a few bags, and grabbed his computer and a charger for his medical device. After that, he said he used his cane to break a window and toss out his bags before rushing from the burning house.

Investigators doubted Compton's story.

For starters, the fire had begun in multiple locations. There was the telltale smell of gasoline on the scene and on Compton's clothing and shoes. He also gave conflicting evidence. So, the police got a search warrant to look at data from Compton's pacemaker, including his heart rhythm and heart rate, according to a report in the local Journal-News.

The data contradicted Compton's version of events, said a cardiologist who reviewed it:

"[I]t is highly improbable Mr. Compton would have been able to collect, pack and remove the number of items from the house, exit his bedroom window and carry numerous large and heavy items to the front of his residence during the short period of time he has indicated due to his medical conditions."

Compton was arrested and charged with arson and insurance fraud. The pacemaker's data was "one of the key pieces of evidence that allowed us to charge him," Lt. Jimmy Cunningham told a local television station.

His attorney last year argued the use of that data violated his client's Fourth Amendment right to privacy, which protects against unreasonable search and seizure. A judge disagreed, saying information about someone's heart rate "is just not that big a deal."

Compton's case is still awaiting trial.

Welcome to the new digital age, when the devices that surround us can become star witnesses in our prosecution. Data from fitness trackers has called BS on multiple suspects' alibis. And police included recordings from the always-listening Amazon Alexa digital assistant in an investigation of at least one murder case.

Such instances raise important issues that legal and privacy experts — and the courts themselves — are only beginning to wrestle with. Not least: How the use of such data jibes with the Fifth Amendment, which protects against self-incrimination, and the HIPAA federal medical privacy act, which lays out how medical data can be disclosed to law enforcement.

"The law and public policy still need to grow to address the tension between individual privacy, the convenience of technology, and governmental invasion and access to private information," says Stephanie Lacambra, an attorney with digital rights group Electronic Frontier Foundation.

"Just where and how to draw the line over what kinds of information should be protected is one that courts and jurists continue to grapple with."

Our data, ourselves

Richard Dabate was found bleeding, his arm and leg lashed to a kitchen chair with zip ties. It was two days before Christmas in 2015, and a trail of blood led to the basement of Dabate's home just outside Hartford, Connecticut.

Dabate told police a masked intruder had killed his wife, Connie, and tortured him. With no witnesses and no suspects, police turned to a smorgasbord of digital devices for clues, from the house's smart home security system to phone records, Facebook posts and a digital key fob.

But Connie Dabate's Fitbit was perhaps the best witness of all.

Its data showed she'd walked 1,217 feet after getting home from exercise class — far more than the 125 feet in Richard's scenario, when he told police she'd run straight to the basement from the garage. The Fitbit also revealed Connie had wandered around the house until nearly 10 a.m., yet Richard had said she was killed about an hour earlier.

Dabate is free on $1 million bail while he awaits trial.

Prosecutors in Australia last week called data from Myrna Nilsson's Apple Watch"a foundational piece of evidence" in charging her daughter-in-law Caroline Nilsson with Myrna's murder.

Police were first called to Myrna Nilsson's in September 2016 after Caroline Nilsson came out of the house "gagged and distressed," according to reports from the Australian Broadcasting Commission. Caroline told police that Myrna was followed home by two men, and that the three of them argued outside the home. She did not hear the fatal attack because she was in the kitchen with the door closed and she was tied up by the attackers shortly after, saying she came out of the house as soon as they'd left.

But prosecutor Carmen Matteo said evidence from the victim's Apple Watch showed Myrna Nilsson being ambushed and attacked as she walked into her home just after 6:30 p.m. -- more than three hours before Caroline had emerged from the home.

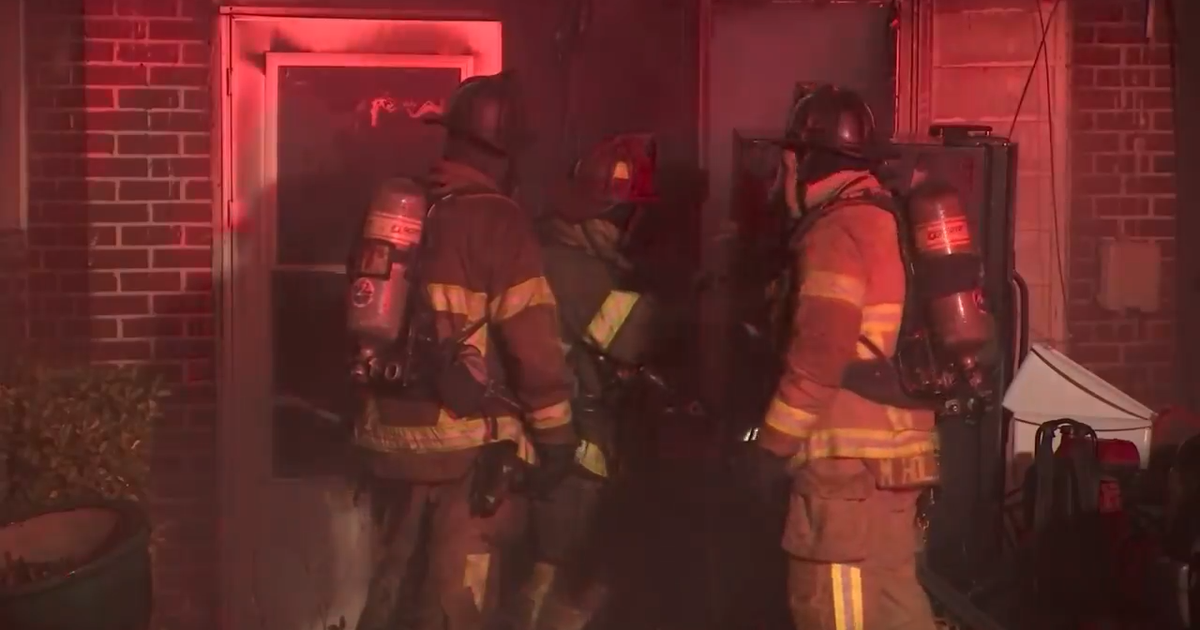

And Bentonville, Arkansas, police suspected James Bates in the death of his friend Victor Collins, found floating in Bates' hot tub in November 2015. Broken glass lay scattered on the patio. Blood drops were splattered near the tub. Investigators turned to a variety of internet-connected devices for evidence.

Data from Bates' smart utility meter showed that someone had used 140 gallons of water between 1 and 3 a.m. To investigators, that indicated the patio had been hosed down before they arrived. Records from Bates' mobile phone suggested he'd made phone calls after he said he'd gone to bed.

But police also wanted to hear audio from Bates' always-listening Echo, which streams audio to the cloud, including a fraction of a second before hearing someone say "Alexa." Amazon initially objected to the request for data, citing the First Amendment, but handed it over when Bates said he had nothing to hide.

In November, a judge dismissed the murder charge after prosecutors said evidence supported more than one reasonable explanation.

Constitutional debate

Can evidence from our digital spies stand up in court?

Brian Jackson, who focuses on technology and criminal justice for the RAND Corp., thinks the Fifth Amendment might offer a defense, especially for cases like Compton's.

"When does access to that data begin to look less like police searching through someone's belongings and more like forcing someone to testify against themselves — something the Constitution provides specific protection against?" he says.

But constitutional scholars say even that may not be enough to get such evidence thrown out.

In Fisher v. United States, for example, the Supreme Court held the Fifth Amendment only "protects against 'compelled self-incrimination, not [the disclosure of] private information,'" according to analysis of the court's 1976 ruling published by Juris Magazine. In other words, "the fact that the data contains incriminating evidence is irrelevant," the Duquesne law school publication wrote last year.

"I cannot imagine a defense attorney seriously believing they could succeed in suppressing this information if it's obtained with a warrant," says Carrie Leonetti, an associate professor of constitutional law at the University of Oregon.

"Do I think that this information should have more protection? Sure, but I'm a card-carrying member of the Tin Foil Hat Society."

In other words, Big Brother may be on your wrist, in your room — or inside your heart.