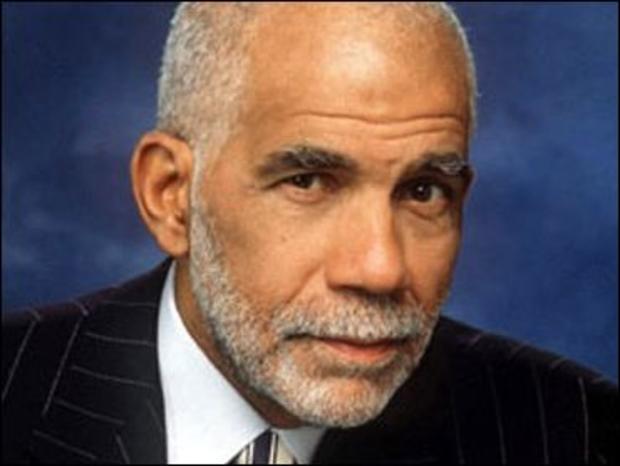

Ed Bradley

Ed Bradley, one of journalism's brightest stars whose name was synonymous with the CBS News magazine 60 Minutes on which he reported for the past 25 years, died Thursday, November 9, 2006, in Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York City. He was 65 and died of complications from chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Bradley lived in New York, but also had homes in Woody Creek, Colorado, and East Hampton, New York.

Bradley spent nearly his entire 39-year career with CBS News, where he rose to the pinnacle of journalistic achievement, at first on the CBS Evening News and on CBS News documentaries and then on 60 Minutes, where he compiled an extraordinary body of work that featured a keen talent for the interview and an intense curiosity shown in his investigative work. He was an elegant gentleman who was also known for his impeccable clothing and style, which included a small earring in his left ear that he wore since the late 1980s, and a short, distinctive beard.

Bradley was among the first black journalists to make a name for himself on national television when his battlefield reporting from the Vietnam War — in which he was wounded in 1973 — pushed him onto the national stage. He never forgot his roots, and spent many hours of his scarce free time talking to young minority journalists. A few years ago, he provided a significant amount of money to seed an annual $10,000 award given each year in his name by the Radio and Television News Directors' Association to a promising minority journalist.

His career gradually built with reporting stints on Capitol Hill, then as White House reporter and then as the principle reporter for the renowned documentary series "CBS Reports." Bradley became one of the most recognized journalists in America soon after joining 60 Minutes. He was listed high on the list of "most trusted TV news personalities" in a 1995 poll published by TV Guide. In the same poll, he was rated second — right behind Walter Cronkite — in competence.

Don Hewitt, 60 Minutes founder and former executive producer, says he first noticed Bradley in a 1979 "CBS Reports" documentary about Southeast Asian refugees, "The Boat People," in which Bradley was filmed helping weak survivors struggling in the surf. Hewitt then picked him to join Mike Wallace and Morley Safer in 1981 on the mega-hit news magazine that finished second in the ratings in Bradley's first season and then topped the list the next with 34.2 million viewers.

Bradley's true talent was his ability to do any story and look natural doing it, whether clowning around with Robin Williams, probing company executives in an investigation or conducting sensitive interviews with bereaved people. The range of Bradley's immense talent was demonstrated almost immediately on 60 Minutes with two Emmy-Award winning interviews in his first few seasons. In the first, an insightful profile of Lena Horne, the fragile singer became so comfortable with the young Bradley, she unconsciously grabbed his hand as they walked.

A few months later, his combative interview with murderer/author Jack Henry Abbott was palpably intense, one in which Bradley recalled being nervous as Abbott fingered a pen that Bradley thought the killer might have stabbed him with. A more recent Emmy-winning jailhouse interview evoked the Abbott episode: Bradley's gripping interview of condemned Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh in March 2000, the only one for television McVeigh gave. It was marked by powerful questions and answers, intense stares and at times, telling silence.

Bradley built on his work with more award-winning stories for 60 Minutes for a total of 20 Emmys and recognition from all of journalism's most prestigious awards. He won a George Foster Peabody Award for "Big Man, Big Voice" (November 1997), the uplifting story of a German singer who became successful despite significant birth defects. In 1995, he won his 11th Emmy Award for a 60 Minutes segment on the cruel effects of nuclear testing in the town of Semipalatinsk, Kazakhstan, a report that also won him an Alfred I. duPont-Columbia University Award in 1994. Also in 1994, he was honored with an Overseas Press Club Award for two 60 Minutes reports that took viewers inside sensitive military installations in Russia and the United States. In 1985, he received an Emmy Award for "Schizophrenia," a 60 Minutes report on that misunderstood brain disorder. He received an Alfred I. duPont-Columbia University Silver Baton and a 1991 Emmy Award for his 60 Minutes report "Made in China," a look at Chinese forced-labor camps, and another Emmy for "Caitlin's Story" (November 1992), an examination of the controversy between the parents of a deaf child and a deaf association.

Some of the more prominent investigative work carried out by Bradley included one of his last reports, an investigation of the Duke University lacrosse rape case, in which he broke new ground with the first interviews with the accused in a story that made headlines just last month; a report on the recalled painkiller, Vioxx, in November of 2004; an expose on the inclination of Ford Explorers with Firestone tires to roll over in crashes in 2000; a 2004 segment that reported the reopening of the 50-year-old racial murder case of Emmett Till; and a look at anti-gay feeling in the military that played a role the beating death of Pfc. Barry Winchell at Ft. Campbell, Kentucky, broadcast in 2003.

He also reported hour-long specials, among them a 1997 report "Town Under Siege" about a small town battling toxic waste that was named one of the Ten Best Television Programs of 1997 by Time magazine.

Prior to joining 60 Minutes, Bradley was a principal correspondent for "CBS Reports" (1978-81), after serving as CBS News' White House correspondent (1976-78). He was also anchor of the "CBS Sunday Night News" (November 1976-May 1981) and of the CBS News magazine "Street Stories" (January 1992-August 1993).

Bradley was responsible for some of "CBS Reports'" finest hours, including: "Enter the Jury Room" (April 1997), an Alfred I. duPont-Columbia University Award winner that revealed the jury deliberation process for the first time in front of network cameras; for "In the Killing Fields of America" (January 1995), a documentary about violence in America, for which he was co-anchor and reporter, that won the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Awards' grand prize and television first prize; "The Boat People" (January 1979), which won duPont, Emmy and Overseas Press Club Awards; "The Boston Goes to China" (April 1979), a report on the historic visit to China by the Boston Symphony Orchestra, which won Emmy, Peabody and Ohio State Awards, and "Blacks in America: With All Deliberate Speed?" (July 1979), which won Emmy and duPont Awards.

Edward Rudolph Bradley, Jr. was born on June 22, 1941 in Philadelphia and attended local schools. He graduated from Cheyney State college in 1964 with a degree in teaching and taught sixth grade for three years in Philadelphia. He got a taste of his future when he moonlighted at WDAS radio, doing the odd job for little or no money. "I knew that God put me on this earth to be on the radio," he said years later. He covered basketball games, spun records and read the news for the station until one day in the middle 1960s when he heard about the riots in Philadelphia on the radio. He offered to cover the story for WDAS and wound up reporting the event in phone call interviews with community leaders. When he returned to the station, they sent him out with a recorder. Bradley never looked back and reporting became his passion.

He soon landed a job at WCBS radio in New York, where he asserted himself and argued with his editor that he would not only cover black issues, he would cover all stories. After a few years, he quit his job and moved to Paris on a romantic whim soon dashed when he ran out of money. Bradley went back to his second love, reporting, and was freelancing for CBS News when they offered him a job covering the war in 1972. In Cambodia, he was hit by shrapnel in the arm and in his back in 1973 and was soon transferred to the Washington bureau to cover Capitol Hill. It was boring work to Bradley and he couldn't wait to get back to the war. He then volunteered to cover the fall of Vietnam and Cambodia and was one of the last reporters to leave both war zones when they fell to the Communists in 1975.

Upon returning to the states, he covered the Carter presidential campaign and became White House correspondent in the Carter White House before beginning his work on "CBS Reports."

Among Bradley's passions was his lifelong love of and dedication to jazz sealed, when he worked at a Philadelphia radio station. He was a board member of Jazz at Lincoln Center and was instrumental in helping create the new facility there for that genre of music. He was also the voice of "Jazz from Lincoln Center," a program carried on National Public Radio in which Bradley narrated concerts dedicated to specific jazz greats. Aficionados could also hear his familiar voice on public radio station WBGO, where Bradley voiced the Newark, New Jersey station's identification, "The greatest jazz station in this country. WBGO Newark."

Jazz music was at the center of many things Bradley did - it was always playing in his office and it was the theme of what he considered his best work. The interview with Lena Horne was what Bradley would answer when asked what his best interview was. Of the interview in which Horne poured out her soul to Bradley, he said, "When I get to the pearly gates and St. Peter asks what have I done to gain entry, I'll say, 'Have you seen my Lena Horne interview?'"

Bradley is survived by his wife, Patricia Blanchet and Reba E. Gaston, his aunt, of Dayton, Ohio.