PG&E Rejected Shut-Off Valves Before San Bruno Blast

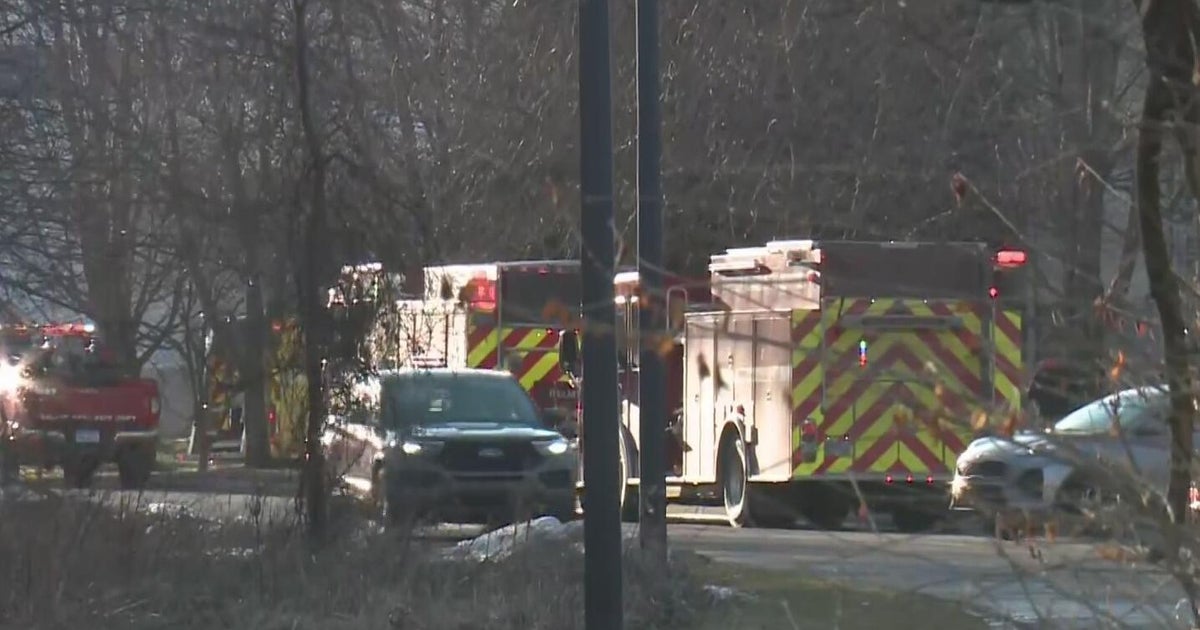

WASHINGTON, D.C. (CBS / AP) -- Pacific Gas and Electric Company officials acknowledged Tuesday that they rejected installing valves that could have automatically shut off or remotely controlled the flow of gas in event of an accident such as September's San Bruno pipeline explosion that killed eight people.

>>Photo Gallery: San Bruno Explosion

Company employees were questioned at a National Transportation Safety Board hearing about a company 2006 memo that said installing the valves would have "little or no effect on increasing human safety or protecting properties."

Gas engineer Chih-hung Lee, author of the memo, said he considered only industry studies, not government studies, in reaching his conclusions. Industry studies, he said, found that most of the damage in gas pipeline accidents occurs in the first 30 seconds after the accident.

However, when the pipeline ruptured on Sept. 9 underneath a San Bruno subdivision, gas continued to feed a pillar of fire for an hour and a half before workers could manually shut off the flow. Eight people were killed, many more injured and dozens of homes destroyed.

KCBS' Holly Quan Reports:

Investigators pointed to a 1999 U.S. Department of Transportation study that warned that there is a significant safety risk as long as gas was being supplied to the rupture site and operators lacked the ability to quickly close manual valves.

"Any fire would have greater intensity and would have greater potential for damaging surrounding infrastructure if it is constantly replenished with gas," the government study said. "The degree of disruption in heavily populated and commercial areas would be in direct proportion to the duration of the fire."

Coroner's reports indicate at least five of the people killed in San Bruno were trying to flee when they died.

Keith Slibasager, PG&E's manager of gas system operations, estimated it took control room employees about 15 minutes following the explosion to figure out what had happened. He estimated it would have taken about another 15 minutes to shut off the gas using automatic or remotely controlled valves, effectively putting out the San Bruno fire about an hour earlier.

About 12 minutes after the San Bruno explosion, PG&E's dispatch center sent an off-duty employee to investigate the reported explosion, but he wasn't qualified to operate the manual valves needed to shut off gas feeding a huge fire that consumed homes, the safety board's lead pipeline investigator, Ravi Chhatre, said.

It took 30 minutes after the rupture for the company to dispatch a crew capable of isolating the pipeline and 90 minutes for them to crank the valves shut, stopping all gas was stopped, he said.

PG&E officials acknowledged that after Lee's memo they made no effort to further explore the valves. They said that since the disaster, the company has begun a pilot project to install a dozen of the valves this year and study their effectiveness.

But Slibasager said there are potential safety drawbacks to the valves. When closed, they could cause widespread gas outages in the region that would put out pilot lights in homes and other buildings, he said. That poses the risk that when gas is turned back on, it could build up in buildings in which pilot lights are not relit right away, he said.

Lee's memo was at odds with an early report by another PG&E employee. The employee, Bob Becken, was assigned in 1996 to study the effectiveness of remote-control valves suggested that more needed to be installed in the system.

Becken rejected the other type — automatic control valves — as unreliable.

But Becken wrote in a memo released Tuesday by the NTSB that he had "no concerns" about installing remote-control valves. "There are existing places within PG&E's gas transmission system where we should consider installing them in the future," he wrote.

The safety board has been recommending the devices to industry and regulators for decades for gas distribution lines, which are larger than the transmission line that ruptured in San Bruno.

The utility has said it installed approximately 60 remote-control valves over the past several decades across its 6,700 miles of transmission lines. That's about one for every 111 miles of pipeline on average.

Tuesday's hearing also focused on PG&E's erroneous listing of the San Bruno pipeline as a "seamless" line, considered stronger than pipelines that have been welded together. It was discovered after the accident that welded pipe was used in San Bruno and that the welds were inferior.

In documents released Tuesday, PG&E said its personnel improperly relied on records from the utility's accounting department to determine the type of pipeline, rather than engineering documents that showed the correct type.

Pipeline safety expert Richard Kuprewicz pointed out that he had seen older infrastructure with better records in tact than what's been revealed about PG&E's Peninsula system. Kuprewicz is a pipeline safety consultant based in Washington State who has been following the investigations into the blast and was monitoring Tuesday's hearing for KCBS radio.

Listen to Kuprewicz comments:

(© 2011 CBS Broadcasting Inc. All Rights Reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed. The Associated Press contributed to this report.)