North Bay Tribe That Runs Casino Could Kick Out Dozens Of Members

GEYSERVILLE (KPIX 5) -- A Bay Area Indian tribe that runs a well-known casino could take some potentially drastic action. More than 70 members could get kicked out.

The tribe runs River Rock Casino. The tribe's chairman has acknowledged in published reports that revenues are down more than 30 percent since Graton Casino opened nearby.

One family KPIX 5 talked to said the ousters are not a coincidence.

Stan and his brother Gregg Cordova are former chairmen and raised their families along the same road that now leads up to River Rock Casino.

Though elders were opposed, Stan said he supported the decision for the Dry Creek Rancheria Band of Pomo Indians to bring in a casino back in 2002. "Maybe it would be good for our family," he said.

And at first it was. The tribe gave the Cordova's money to relocate. Like every member, they got monthly per capita casino checks.

But as cash started rolling in, Stan said the love of money came in. So did a new chairman, and then, the letters.

Stan's letter said he "did not qualify for membership" because he previously had been a member of his mother's tribe, another branch of the Pomos.

Two years later, Stan's daughter Carmen received a letter saying she had a "break in lineage." "It feels like a piece of you is getting ripped out," she said.

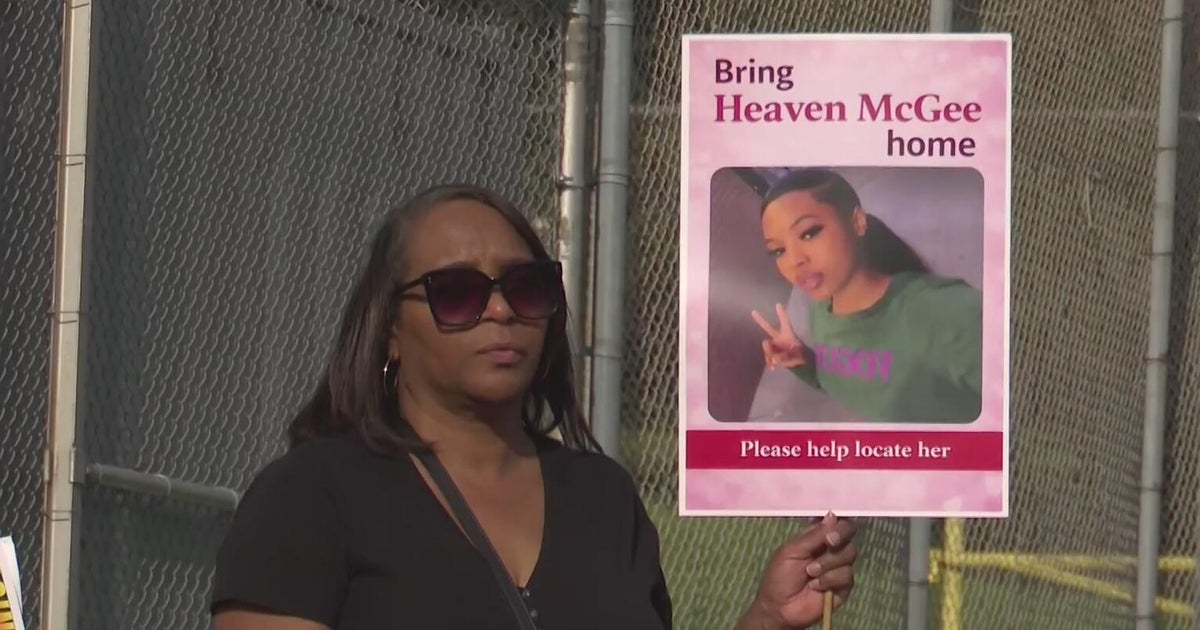

Carmen and her father got kicked out. Now her brother, her cousins and all their children received letters. The entire Cordova family could get wiped off the tribal rolls.

"They have no reason to go after our children! For what? It's just money and greed, that's all," said Cody Cordova.

The Cordova's are getting kicked out of their own tribe through a process called disenrollment.

KPIX 5 asked Dry Creek's board of directors why. They said it's confidential, and they can't talk about it. The family is among more than 70 that will appear before the tribal council later this week, at the Dry Creek Rancheria headquarters in Santa Rosa.

Laura Wass with the American Indian Movement says disenrollments are happening across California, thinning the tribe so fewer families can get a bigger piece of the jackpot.

"The reasons are not justified, none of them. They are blood people sharing the exact same history," she said.

A history that saw outsiders nearly wipe the Pomos off the planet. Now Wass is concerned insiders will finish the job.

"The extermination period in California got rid of over 90 percent of the Indians. This is coming doggone close," she said.

Keep in mind, it is the tribes themselves that came up with disenrollment as a way to deal with frauds who might claim false heritage. But the folks we talked to in this story insist they have been documented members of the tribe ever since records were first kept.

And the families don't have any recourse, because the tribes are considered sovereign nations and the Bureau of Indian Affairs does not intervene in tribal politics. Wass is calling for a congressional hearing, to force Washington to do something about it.