"Mass killers practice at home": How domestic violence and mass shootings are linked

Before 20 children died in a shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School, and before 19 students died at Robb Elementary School, the shooters turned their guns on family members. The man who shot his five children, wife and mother-in-law in Enoch, Utah, in January had previously been investigated for allegedly choking his daughter. Just Friday, prosecutors said an Ohio man killed his three sons with a rifle and shot his wife as his daughter ran to get help.

As rates of gun violence increase in the United States, experts have identified a disturbing, decades-long trend: There's a clear intersection between mass shootings and domestic violence toward family members.

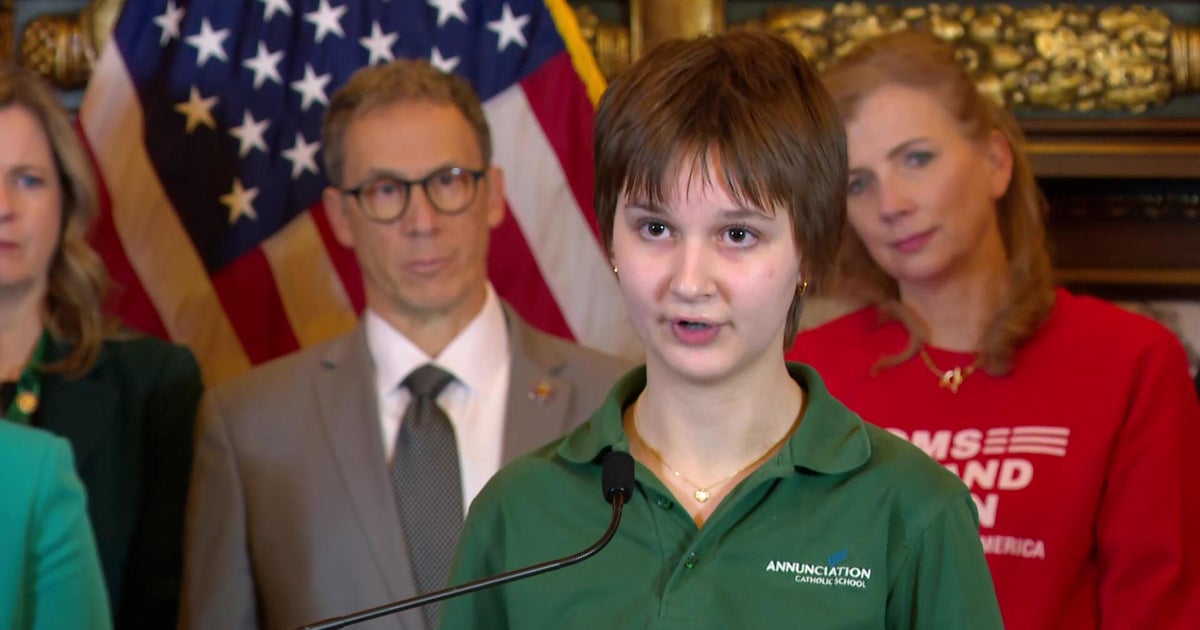

More than half of mass shootings — those involving four or more victims — are "actually shootings of intimate partners and families," said April Zeoli, Ph.D., an associate professor and the policy core director for the Institute for Firearm Injury Prevention at the University of Michigan. Zeoli studies the intersection of domestic violence, gun violence and policies aimed at curtailing both.

Even in cases where family members and partners are not killed, the perpetrators of mass shootings often have a history of domestic violence, she said.

"Taken together, around 68% of mass shooters either killed their family and intimate partners, or they have a history of domestic violence," Zeoli said, citing a study that looked at the links between domestic violence and fatal mass shootings between 2014 and 2019. Mass killings committed by a family member far outnumber public mass killings, according to a dataset compiled by USA Today, the Associated Press and Northwestern University. Such incidents are seven times more likely to take place in a home or other shelter — and one has occurred, on average, every 3.5 weeks for the past two decades.

"If we ask what mass killers have in common, we note that they are almost all men, and that they have a history of controlling and abusing their wives and girlfriends — and sometimes other family members — before 'graduating' to mass killings," said Lisa Fontes, Ph.D., a psychologist and senior lecturer at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and the author of a book about overcoming controlling relationships, in an email to CBS News.

The connection between domestic violence and mass killings

In many cases, guns start as a way to control, coerce or threaten victims, experts told CBS News.

Firearms "are an ever-present tool of terror," Zeoli said. "We know that they're used to intimidate. They're used to coerce. They're used to threaten people ... and even when the gun isn't being actively used or threatened, it is there and the victim knows it can be used or threatened, and so that leads to increased stress and increased terror over and above what is present in a relationship with domestic violence that doesn't involve guns."

Zeoli said that when a male domestic abuser has access to a firearm, his female partner's chances of being killed "increase by fivefold." Research has not looked at the risks male partners face when a female domestic abuser has a firearm, she said.

A key problem is the easy availability of firearms, researchers said. In 2020, there were an estimated 433.9 million guns in the American civilian population, according to the National Shooting Sports Foundation, which draws on multiple sources to publish firearm production reports. That's about a hundred million more guns than people.

Some states have begun working to protect victims of domestic violence and the public with extreme risk protection orders, also known as red flag laws, which can temporarily prohibit a person from owning or possessing firearms. A 2022 study worked on by Zeoli and Shannon Frattaroli, Ph.D., an associate professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and a member of the school's Center for Gun Violence Solutions, with other researchers, found that when people threatening a mass shooting named a potential victim, that victim was "very often a partner," Frattaroli said, or family members. The only targets threatened more often than intimate partners were K-12 schools and businesses.

While that study only looked at threats of violence, real-world situations have shown similar connections. In addition to the shootings at Sandy Hook, Robb Elementary, and in Enoch, Utah, a man who killed nine co-workers at a rail yard in California in 2021 had an alleged history of domestic violence, as did the gunman who killed 50 at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando in 2016. The man who killed 26 at a church in Sutherland Springs, Texas, the following year, had been court-martialed for assaulting his wife and stepson.

"If we look beyond domestic violence, which is usually considered violence against an intimate partner, we can see that an even larger number of mass killers practice at home — committing violence against family members before they strike out in public," Fontes said.

How does domestic violence escalate to a mass killing?

A violent relationship is most likely to turn fatal when women are in the process of separating from an abusive partner, said Walter Dekeseredy, Ph.D., a professor of sociology at the University of West Virginia and the director of the school's Research Center on Violence.

During that time, Dekeseredy said, there is a "sixfold increase in the risk of a woman being killed."

In the case in Enoch, Utah, wife Tausha Haight had filed for divorce from her husband just weeks before the family was killed.

"What echoes if you talk to any police officer, homicide detective, what echoes through the homicide data are the words 'If I can't have you, no one can,' and so the murder is like a murder of the separation itself," Dekeseredy said. "These guys, they just can't handle the women leaving."

The fear of violence is a key part of why people may stay in abusive relationships, said Kirk Burkhalter, a professor of law at New York Law School and the director of the 21st Century Policing Project. Before his legal career, Burkhalter was an NYPD officer for over two decades, retiring as a detective. He agreed with Dekeseredy's assertion that the moment of leaving is the most dangerous part of an abusive relationship, and can lead to the violence that a victim has been threatened with becoming real.

"One reason why many people stay in abusive relationships … is the fear of violence," Burkhalter said. "The nature of abuse is such that it's not done because the abuser is trying to push the person out of the home. In many cases, or most cases, it's done because the abuser wants to exercise a continued level of control and power over the victim. And you can't do so if the victim leaves."

In domestic abuse cases, Fontes said, the perpetrators of violence have often "become increasingly threatening and controlling" in the time before their partner contacts law enforcement. However, an abuser "may discover that there are few to no consequences for his behavior, depending on the jurisdiction and how seriously they take domestic abuse," leading to an escalation.

"He may cross the line on protective orders. He may refuse to make court-ordered child support payments. His anger and sense of entitlement grow and are not contained," Fontes said.

Zeoli and Frattoroli both said that it isn't a surprise to researchers that a person who harms intimate partners or family members would then escalate to hurting strangers.

"There is something to be said for being willing to use violence against the people you love and also being willing to use violence against strangers," Zeoli said.

Do red flag laws help?

At the federal level, domestic violence is the only type of crime specifically referenced in federal firearm restrictions, Zeoli said. People under a current domestic violence restraining order and those convicted of a misdemeanor domestic violence charge cannot purchase or possess firearms, she said, and some states have enacted their own versions of these laws. The impact of this legislation has been "statistically significant," Frattaroli said, especially in states where people with a domestic violence protection order cannot purchase or possess firearms.

In states with red flag laws or extreme risk protection orders, firearms can be confiscated in some cases. Fontes said that these laws, when they are enacted and enforced, have "made a huge difference."

"What this research suggests is that people are turning to the courts turning to extreme risk protection orders to use this tool to temporarily remove guns from people who are behaving in a way that suggests that they might be planning to commit a mass shooting event," Frattaroli said. States with rules that say someone with a domestic violence protection order against them cannot purchase or possess guns have reduced the number of murders of partners, she said.

While these efforts are working, they aren't necessarily foolproof: Red flag laws aren't always enforced properly, and a restraining order may not always be obeyed.

In Colorado Springs, a shooter killed five and injured dozens at Club Q, a popular LGTBQ+ nightclub. Previously, the shooter had made a bomb threat in El Paso County, Colorado, and according to arrest records from that incident, threatened to stockpile guns and expressed a desire to be "the next mass shooter." The defendant also threatened to kill their grandparents if they interfered in that, CBS News previously reported.

The county and sheriff's office had previously announced its opposition to the state's red flag laws, which had been enacted in 2019, CBS affiliate KKTV reported. Victims have filed notices they intend to sue the sheriff's office, alleging the violence "could have been avoided" if the sheriff's office had enforced the state's red flag law, according to KKTV.

While when a perpetrator of domestic violence is not supposed to have or be able to purchase guns, there are loopholes that can allow them to gain access. Even when red flag laws or protection orders are properly used, the person's guns are returned to them after the orders expire.

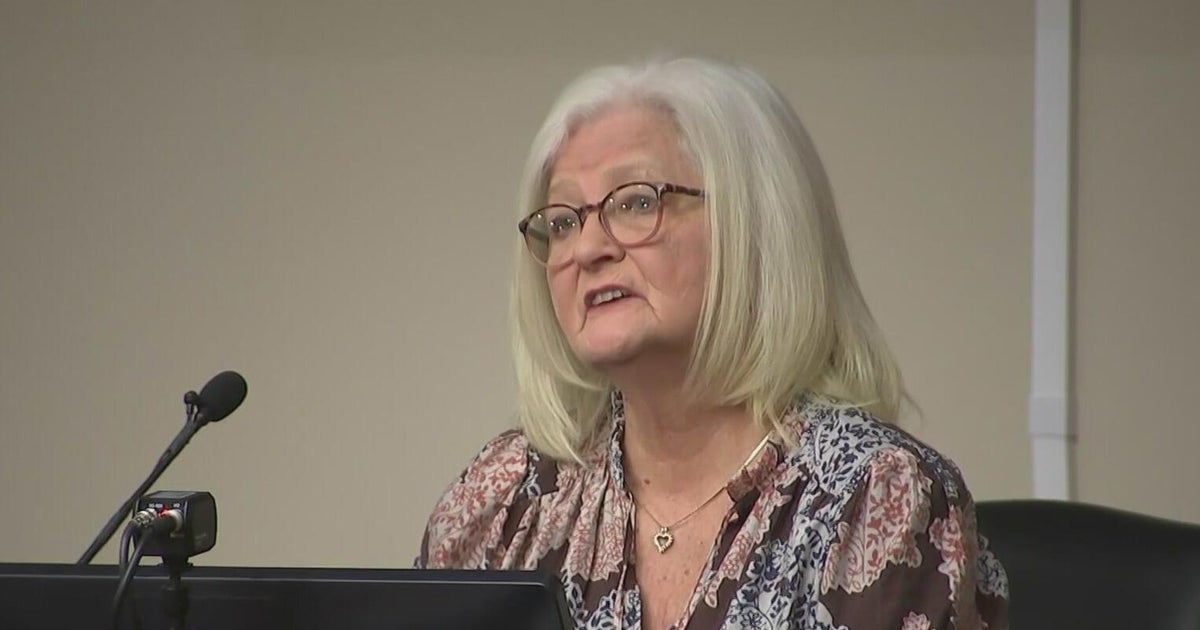

"I cannot even begin to describe to you the terror that many women live in when they have successfully separated from their abuser, and the police return guns to their abuser," Fontes said.

To really break the cycle between gun violence and domestic violence, Zeoli said the United States needs to look at longer-term answers, not just legislative solutions. That means working to prevent domestic violence in the first place, she said, and restricting access to guns nationwide.

"Firearm violence is preventable. We have research that suggests that there are these laws that work to prevent intimate partner homicide. There are other laws that work to prevent gun violence," she said. "This is not a situation where we can't make a difference, where we have to live with gun violence. We absolutely don't."