Lyft Set To Become Latest Tech Company To Nearly Eliminate Shareholder Power

SAN FRANCISCO (CBS SF) -- Members of the public who buy shares of Lyft after the company's initial public offering on Friday will find they have little or no voting power. The company's co-founders are retaining nearly a majority of shareholder votes by issuing themselves supershares.

According to recent filings with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, Lyft will issue two classes of stock. The filing reads, "Each share of Class A common stock is entitled to one vote. Each share of Class B common stock is entitled to 20 votes and is convertible at any time into one share of Class B common stock."

The public can only purchase the Class A stock.

After the IPO, all of the Class B stock will be owned by Logan Green, Lyft co-founder, Chief Executive Officer and John Zimmer, Lyft co-founder and President.

Investors are warned in the filing, "...upon the closing of this offering, our Co-Founders will together hold all of the issued and outstanding shares of our Class B common stock and therefore, individually or together, will be able to significantly influence matters submitted to our stockholders for approval, including the election of directors, amendments of our organizational documents and any merger, consolidation, sale of all or substantially all of our assets or other major corporate transactions."

Specifically, after the IPO, Green will have 29.3 percent of the total shareholder voting power and Zimmer will have 19.45 percent of the total voting power, for a combined total 48.75 percent.

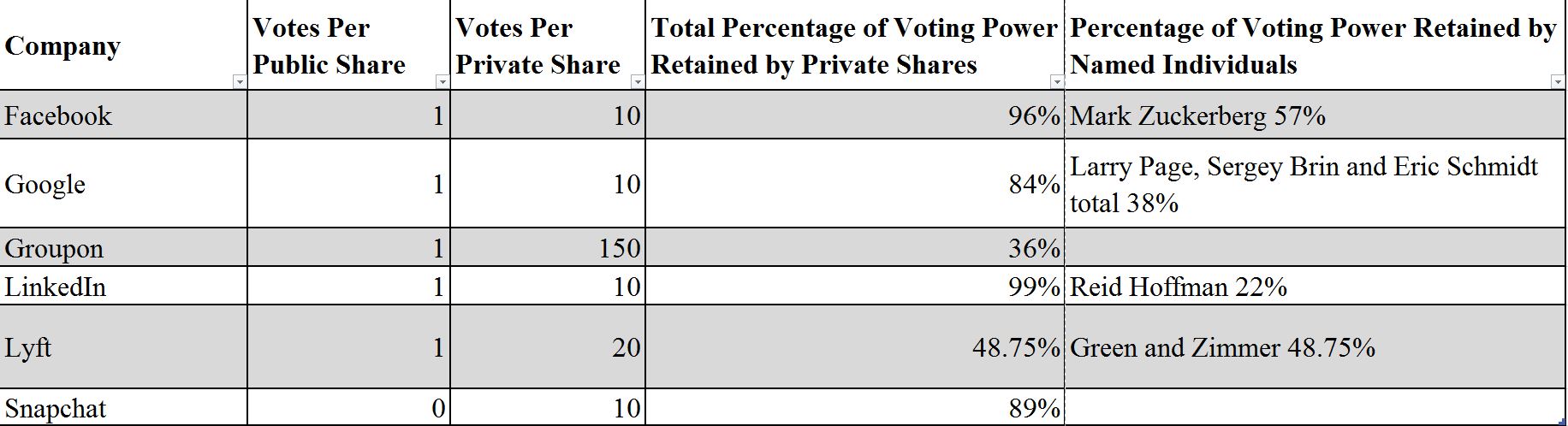

Lyft is far from the only company using this tactic. Starting with Google in 2004, a number of tech companies have gone public and retained control over company decisions by issuing two tiers of stock. Here are the immediate post-IPO statistics of just a few:

"They want to make sure that, while they take Wall Street's money they don't have to take Wall Street's advice all the time." The thinking is, "Wall Street may know spreadsheets, but they don't know semiconductors."

Still, tech is one area where companies seem most inclined to go public without losing control, says Jeremy C. Owens, the San Francsico Bureau Chief and Tech Editor for Marketwatch.

It's not just tech companies who use this method; Levi's Strauss recently went public with two classes of stock, Class A for sale with a single vote per share and Class B retained by insiders with 10 votes per share. Following the IPO, Class B shareholders retained 99 percent of voting power.

Still, companies that insist on keeping control may forgo access to some big investors.

When Snap (parent company of Snapchat) went public in March 2017, selling shares without any votes at all, Owens says it was a wake-up call.

"That was when everybody realized where this was heading...that if Snap could get away with it, then a lot of other tech companies would want to try as well," said Owens.

In July 2017, some stock indexes like FTSE Russell and S&P Dow Jones announced they would no longer include most newly public companies with different classes of voting shares.

A recent SEC filing by Lyft lays out all the investors for which they are not eligible, "Under the announced policies, our dual class capital structure would make us ineligible for inclusion in certain indices, and as a result, mutual funds, exchange-traded funds and other investment vehicles that attempt to passively track those indices will not be investing in our stock."

Still, companies continue to use the dual-class structure; IPO filings by Pinterest show it plans a dual class structure.

"Each share of Class A common stock will be entitled to one vote. Each share of Class B common stock will be entitled to 20 votes..." read one filing.

There can be a benefit to this sort of system, says Owens. Investors may be happy to let the experts run the show without shareholder interference. For example, "when people bought Facebook, they were buying Mark Zuckerberg," said Owens.

That investment in one or a handful of people can also have a downside. Owens says if Uber had gone public while Travis Kalanick was still CEO, the sale of shares may have been structured to keep Kalanick in charge.

"If those founders mess up, in the way that Mark Zuckerberg has at times, in the way the Travis Kalanick did at Uber and if they don't want to leave, there's very little recourse because they have control," said Owens.

In this "live by the founder, die by the founder" situation, Owens says people buying shares should understand what they're doing: investing in people, not companies. In the case of Lyft, shareholders aren't really investing in a ridesharing company, they're investing in Green and Zimmer.

"You are paying for those founders to run that company; you're not buying into the company itself," said Owens. "You're buying those founders."