Crisis of missing, murdered Indigenous women rooted in historical wrongs

Unseen: A California crisis of missing, murdered Indigenous women - Part 3

Tonight, we shed more light on the Unseen - the missing and murdered Indigenous women in California and some factors that make them more vulnerable, by turning the page to one of the most heinous chapters in the state's history and how the consequences continue to be felt.

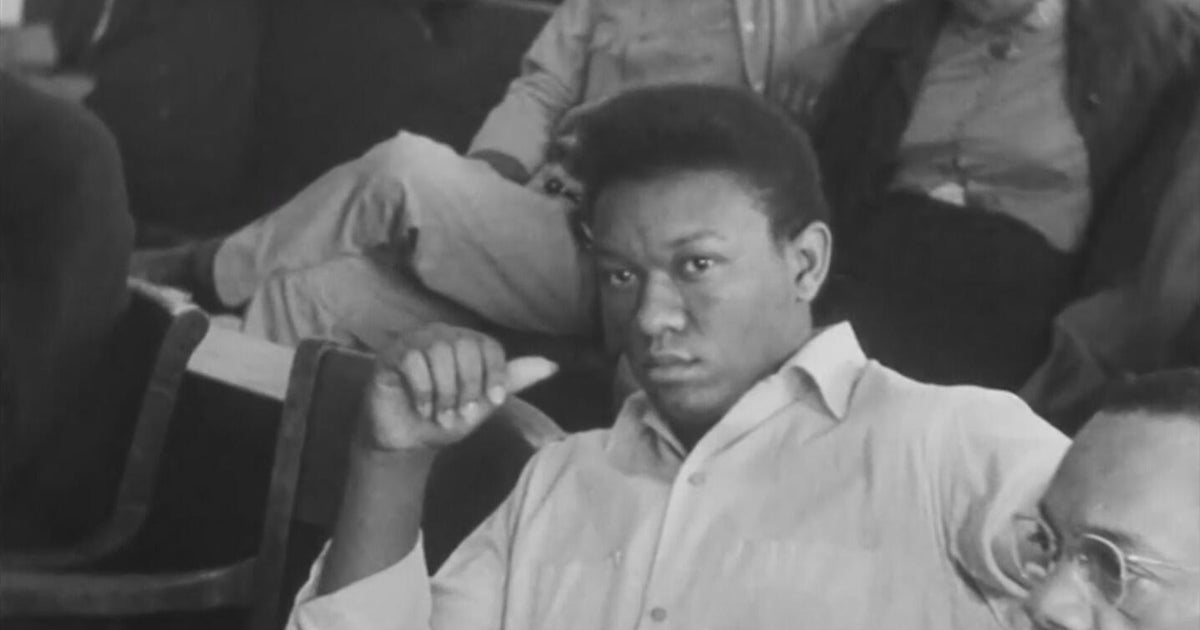

Redwood canoes are once again gliding on the Klamath River. For Yurok Tribe Councilmember Phillip Williams, it's a way to connect to his ancestors.

"You're actually getting a glimpse of our way of life before colonization," said Williams. "It's important that we don't lose this culture."

For thousands of years, these hand-carved dugout canoes traveled the river. The Yuroks revived the tradition, but it's not just the canoes that nearly went extinct.

During the gold rush, government officials funded a campaign to slaughter California's Indians. In just 20 years, 80% of the population was wiped out. Some say this contempt for native life continues to this day. This disregard is now reflected in the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women.

"It's hard to accept the fact that there was a society that wanted you gone," said Williams.

Web Extra: Canoe conversation with Yurok Tribe Councilmember Phillip Williams

For Councilmember Philip Williams, it's personal. His daughter Tara went missing and was later found dead near her crashed truck. There was speculation of foul play. Williams fears he will never really know what happened to his daughter.

"We've been losing people all the time," said Williams. "Unsolved mysteries up here, all the time."

As for the historical wrongs, they include more than the massacres. There was a systematic attempt to erase traditional values, behaviors and beliefs, by forcing Indian children into boarding schools.

"Forget your culture, forget your life," said Williams. "And become assimilated, become a white person."

A recent federal report reveals that from 1819 thru the 1970s, the U.S. operated more than 400 Indian boarding schools. Twelve were in California. Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their families and communities. Children who resisted assimilating were often punished with whippings, solitary confinement, or starvation.

So what do these wrongs have to do with the missing and murdered women?

Yurok Tribe Chief Justice Abby Abinanti believes the traumatized children - some who were legally enslaved - passed their pain, suffering, and coping mechanisms onto the next generations.

"They came home having not been parented, and with a lot of bad habits, because they were beaten or whatever," said Abinanti.

Those habits include substance abuse and domestic violence that can lead to mental illness. The challenge is how to break the destructive cycle; many believe that effort includes reconnecting to traditional values and beliefs.

Yurok Chief Operating Officer Taralyn Ipiña showed us how she gathers acorns, a traditional food used by more than 75% of Native Californians.

"Do you feel that when you gather acorns you're in some way connecting to your grandmother?"

"Oh absolutely I do," said Ipiña.

Ipiña's grandmother was murdered. Recognizing the trauma is helping her break the cycle for future generations.

"We're talking about it talking to my kids about it," said Ipiña. "They didn't know because I didn't talk about it. So painful."

For Williams, reclaiming the Yurok heritage is one step to healing. But, he knows it won't take away the pain from those still waiting for resolution.

"My daughter was found. I can't imagine what it would have felt like if she wasn't found," said Williams. "I have closure. I buried my daughter and they don't have that."