What Hope can do: Holocaust survivor remembers dark days at Dachau nearly 80 years after liberation

"What Hope Can Do," the video attached above, is a documentary streaming exclusively on CBS Sacramento. This final installment in a three-part series produced by CBS13 tells the incredible life story of local Holocaust survivor, Nick Hope.

CALISTOGA, FAIRFIELD — Nick Hope, soon to turn 100, looks back on his long life and chooses not to focus on the atrocities he endured at the hands of evil men.

"Somebody suffers their whole life. I don't. I don't," he said.

Hope is the name he gave himself after surviving World War II and relocating to Northern California. He was born Nikolai Choprenko in 1924 in Ukraine.

Still, there are nights his dreams take him back to horrendous, starving years in Germany at Dachau concentration camp.

"I say, 'No, no, no. Everything is over. Everything is over,'" Hope said.

Both in name and in life, he chose a future of promise over pain.

Before the war

"I was born in a little town, Petrowka," Hope said.

Fond memories from Hope's childhood on his family farm were real, but short-lived; soon, everything changed.

"We were rich. Rich. But it was not long," Hope said.

He was just a child when Joseph Stalin, communist dictator of the Soviet Union, came to power.

"My father's house, they said 'You are rich, you capitalist. You exploit other people.' They confiscate it. Lands. House," Hope said.

Everything Hope and his family had ever known was stolen under Stalin.

"It was a revolution by force. Everything was by force, you know," he said. "What he did, he cut all food, clothes, work, houses – cut off completely. It was 1932, 1933. I was about 9 years old."

Stalin forced brutal famine on the Ukrainian people. The period of suffering and starvation is called the Holodomor.

It claimed millions of Ukrainian lives, including two of Hope's brothers.

Hope remembers all he ate from this point in his childhood into his teenage years was potatoes, sauerkraut, pickles and, on occasion, bread. There was simply never enough to eat and only one set of clothing for each family member.

He was forced to learn Russian and barely survived these formative years.

"This was terrible, terrible. But, we get through," Hope said. "Father worked in the coal mine. They gave us food for the work."

Still, he hoped for a better life.

Click here to watch the first story in CBS13's three-part series on Nick Hope's life.

A premature celebration

War was spreading quickly in Europe and across the world in 1941. The Axis powers and Nazi Germany eyed the Soviet Union and Japan bombed Pearl Harbor later in December, signifying the United States' entrance into WWII.

Hope said, that year, when Hitler invaded his home in Ukraine, people actually celebrated and cheered.

They thought the Germans were freeing them of Stalin and the famine that had plagued them for nearly a decade.

"Oh, this is good, the Germans come and they will help us to create new, everything new. They made a mistake," Hope said.

He was now just 17 and under Nazi rule.

Soon after, Hope said all the Germans living in his town were loaded up and sent back to Germany. This included, to his dismay, a young German girl he had fallen for named Hilda.

"I said goodbye the last night I was there. The next morning, she was gone. Oh, brother. I was upset," Hope said.

Things, of course, did not get better. Hope said Nazi soldiers were on the hunt to find young men to send off to work in Germany.

One day, while waiting in a food line with his friends, they were stopped by Nazis without their proper identification papers.

"They put us in the jail. What can we do now? Next day, next morning, they say, 'Oh, you know, maybe you go to Germany to work. It will be a good life. Make lots of money.' Lying. I would say, 'No. No.'"

Hope said, while imprisoned, the SS guards spun a story that he tried to escape. His punishment was being forced on a train with about 50 other Ukrainian men to work at a German factory. None went willingly.

"So homesick, I thought I'd die"

Hope never got a chance to say goodbye to his family or his friends before he was forced from his home forever.

"'Uh oh,' I said, 'We are in Germany now.' Now we see new life, new start, new future," said Hope.

For the next year, he found himself a slave in Munich at a factory where all labor was forced.

"A military factory where they processed dynamite. Very dangerous," he said. "I'm so homesick, I thought I'd die. I'm 17 years old. My parents don't know where I am, what happened to me. I'm separate from home, friends, family."

They slept twelve people to one barrack and were treated as prisoners. Their bedding was made of paper.

"They promised to pay 20 marks, but this was ridiculous that they pay money. We are prisoners. We can't get out," Hope said.

"It's their way of giving him a job in Germany when in reality, it was slave labor," Hope's son, George, added.

Hope said that with just one set of clothing and no underwear given to them, he hatched up a plan.

"This material, what they didn't use, would go to the trash all the time. I say, 'Listen, we don't have underwear. I can make it out of this thing in the trash there.' I pick it out the trash," said Hope.

Hope stashed the material under his bed, waiting for the right time to make use of it. He was sent to the Gestapo when it was found under his bed in a raid.

"I tried to explain it is garbage. 'Listen,' I said, 'Listen, 11 months no underwear. I want to make out of this.' I can't explain. He just was so mad," Hope said.

For something so simple as taking trash to make underwear — he was sent off to the closest concentration camp.

Destination: Dachau

Hope remembers the open air of the truck bed he was sitting in with six other boys and men as they were driven 20 minutes to Dachau in February, 1943. He did not know exactly what was ahead, but knew it could not be good.

The iron gates to the camp read "Arbeit macht frei" in German, which translates to "Work sets you free."

"We get from the car, step over the threshold and somebody says, 'Okay, that's it.' 'What do you mean that's it?' They sign a cross and say, 'You'll never get out alive. You'll go through the chimney. The smoke coming out only,'" said Hope.

Dachau was the first and longest-running concentration camp established by Hitler's Nazi regime. It served as a model for the concentration camps that followed and was even a training center for SS guards.

Scholars believe that from 1933 through 1945, more than 200,000 people were imprisoned at Dachau, with at least 40,000 people dying, according to the Holocaust Encyclopedia.

"I just have in my mind, I'm going to die here or something, absolutely," Hope said.

Death was everywhere: unavoidable and imminent.

"I remember the smell, like barbeque from bodies, dead bodies. Terrible," Hope said.

He witnessed the unimaginable happening to prisoners daily, recalling the memory of one lost soul on the bottom of a cart of bodies.

"He says, 'Friend, please help me. Help me...' I could do nothing. Alive. Alive, he goes the direction of the crematorium. Terrible. Everything is upside down in my mind," he said.

Hope witnessed senseless killings, a gas chamber that was always running, evil experiments on prisoners and true starvation.

"Always in my mind was bread, bread, bread, bread," he said. "But thanks to my grandfather, he teaches me a lot of things, but patience, any condition, patience."

On to Allach

After three months at Dachau's main camp, Hope was moved to a Dachau substation called Allach for forced labor.

"They put me first on a conveyor, I would put two parts of a cylinder and put together with a special instrument," he said.

Hope was working at a BMW motor factory. The popular company admits today its former, dark connections to the Nazi party at the time.

About half of BMW's workforce during WWII was made up of concentration camp prisoners like Hope.

His two years at Dachau Allach might have saved his life, but they were not any less cruel.

"I hate this place, we suffer so much, you know?" Hope said.

"I won't strike"

Simple mistakes at Dachau Allach warranted brutal beatings by SS guards, lashes to the back. Hope remembers all too well an occasion when he was accused of sabotaging his work at the factory.

"They called, 'Number 44249, step out.' That's my number," he said. "I said, 'Oh my, it's finished.' They bring me to the table, belly down. One guy holds this hand, one guy holds my head and my feet."

Hope says he remembers how the SS guards wished to make a show of every beating. They would force the other prisoners to watch, and at times, worse.

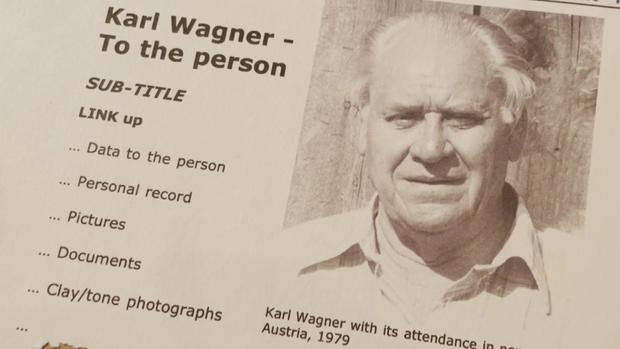

As Hope's number was called out, the Nazis ordered a fellow Soviet prisoner to give Hope his lashings. The prisoner's name was Karl Wagner. He refused to do it.

"He says, 'I can't beat him. I can't beat him,'" Hope remembers. "He suffered for this, for me. Big sacrifice."

Wagner went on to write a book about the encounter, called "Ich Schlage Nicht" in German, meaning, "I do not strike."

Hope was still beaten that day, but not by his fellow Soviet friend. Wagner knew what it would cost him — and took a stand anyway.

"When they finished, I feel like somebody put boiling water on my back. I lost my mind, " Hope said. "There's only bones, no meat there. The next day, I have to go to work."

They slaved on, day in and day out — but soon, the end was near.

Closing in on the camp

April of 1945, American forces were inching closer and closer to Dachau.

Hope said he remembers one day United States bombers dropped leaflets at the Allach camp with a warning: that they were going to bomb the factory that week and civilians should leave.

He witnessed American planes the next morning flying low over them, one of the planes even crashed and exploded, killing the pilot.

"Then a bomb about 20 feet away from me exploded. Covered me with dust and rocks and everything. I say, 'Okay, I'm finished.' But no, I'm still alive," Hope said with a laugh.

The Nazis, in a panic to keep as many prisoners as possible out of Allied hands, forced thousands of people out of the camp on a death march.

Hope was one of them.

"Two days we walk in the rain. It was dangerous, we'd walk and fall down and that's it. You're finished. They'd kill you right away. I hear boom, boom, boom," said Hope, gesturing gunshots.

When all hell broke loose and the Nazis unleashed all their firepower on the lines of prisoners, Hope and a friend took off into nearby woods as the shots rang out, a constant death knell.

"We are free"

What they saw next over the hill as they ran would be life-changing and history-altering.

"Oh, brother. The American tanks come," Hope said. "There's a highway and it's full of tanks, maybe 100 of them. We come out and cry, 'We are free. We are free.' Dancing. Crying. You can't explain it. People just trying for their freedom. They're free, but not all of them," said Hope, choked up with emotion.

So many died on the march — a tragic fate, just before WWII would end in 1945. Thousands, of course, died first in the camp before it all came to its rightful demise.

Hope would soon find refuge in those woods he ran to for cover. American soldiers ordered German farmers there to take in the prisoners.

"He said, 'Hey listen, here's about 100 prisoners give them food, sleep, wash," he said.

At this point, it all sank in.

"We are free. Free forever. Free from this terrible, terrible thing that's behind us," Hope said.

After surviving all of this, Hope almost died simply from eating.

"I go so far, now this is how I should go? No, no, no, no," Hope said while remembering his disbelief in the cruelty of it.

Hope weighed only 75 pounds when Dachau was liberated by American forces. All the food he had eaten in those days after sent his body into shock.

He says when he felt he was truly dying, his mother came to him in a dream.

"My mother says son, 'If you have a problem in your stomach, eat dried pears.' Oh brother I heard that, and it disappeared," he said.

The farmer taking care of him and other prisoners, in the chaos of it all, somehow found a bag of pears.

"He says, 'Here, don't die,'" said Hope.

"How did he find them?" his son George asked with a laugh.

Starting over

Hope would survive thanks to the United States army and a little help from some perfectly timed pears. However, it was an uphill climb from there.

After the war's end, Hope would spend four years at a hospital in Munich recovering. In a beautiful twist of fate, it is where he met his wife Nadia, a fellow Holocaust survivor.

"I tell her, 'This is going to be my wife,' " Hope said. "To the other guys, 'Don't touch her! This is going to be my wife,' " Hope said with a smile.

Hope found his person and a place to start over.

He and Nadia would move to Calisotga from Germany in the 1960s and had three children — Victor, Jenny and George.

Hope would go on to become a renowned builder in the Napa Valley community.

However — before that, moving on after the Holocaust did not come easily.

Years of trauma manifested in anger, overeating and binge drinking.

Hope says only when he found faith, he found hope: Nick Hope; what, and who, he had lost.

"There really came time that I started a new life. New everything. New future. I accept the Lord as my personal savior. I go to the church, was baptized," Hope said.

Finding forgiveness

His faith, in a defining moment, was put to the test while still in Germany after the war.

Years after Dachau, Hope ran into an old Nazi SS commander in public — a man who beat him constantly.

"I heard his voice. My heart almost stopped beating. But the spirit of God says, 'Take it easy. Everything is passed. It is different now,' " Hope said.

Hope said that he followed the now-former Nazi to his home, knocked on the door and found closure.

"I say, 'I come here to forgive you... give me a handshake. I forgive you, everything that you've done to me,' " Hope remembered.

Forgiveness did not come easily — but blotted out the remaining stain of hatred left in Hope's heart.

"That is God's will, that we love each other, not hate each other. This whole terrible, terrible tragedy in the world never, never, never happen again," Hope said.

The other side of the war

Fairfield veteran Dan Dougherty was 18 and an Army solider when United States forces began closing in on Dachau concentration camp in late April 1945.

CBS13 first profiled Dougherty's story on Memorial Day in 2023.

Dougherty served in the C Company of the 157 Infantry Regiment in the 45th Division.

His rifle company had no idea what they were walking into as they approached Dachau that day of liberation.

"We had come upon this long train of box cars. We get up to it and make the horrifying discovery that the cars contained just totally emaciated human corpses. Turns out there were 39 boxcars with 2,310 bodies," said Dougherty.

The soldiers did not even know what a concentration camp was. They could not have imagined the horrors of what the Nazis had been up to.

"Later that morning, we came to a tall picket fence about seven feet high. This turned out to be the perimeter of the camp Dachau Allach. All the sudden, the prisoners realized we were the U.S. Army and the celebration began. We gave them all of our rations, cigarettes, our candy," said Dougherty.

Dougherty remembers he could not sleep that night. His mind was racing with what he had seen and what he still could not understand about the camp.

His platoon was housed for the evening in what had been the home of a former SS commander at Dachau. They left before dawn the following morning to resume the attack on Munich.

"It's caused me to do an awful lot of thinking after the war. How is it possible the most educated, religious, churched society in Europe could produce and sustain the Third Reich? That's a very, very difficult question and it's still being asked. People are still trying to figure out how something like that could happen," said Dougherty.

A reunion: the liberator and the liberated

Dougherty and Hope have both been invited to attend multiple, annual ceremonies held at Dachau concentration camp that celebrate survivors and heroes who helped liberate the camp.

Hope is attending this year with his family as he has in years past. Dougherty has also attended several times over the years.

However, it wasn't until the 2020 coronavirus pandemic forced the annual ceremonies online that Dougherty and Hope connected for the first time.

"Well, I came to Northern California in 1953, Nick came in 1961, I think? So we've lived within an hour of each other, but it wasn't until 2020 that we ever knew each other existed," said Dougherty.

The online celebration made the men of Calistoga and Fairfield realize they were practically in each other's backyards, 75 years after Dachau.

"I had no idea anybody like that lived around here. It's been a big surprise to find out there's a longtime Dachau prisoner living in Calistoga," said Dougherty. "Just an hour away. It was very nice to meet him for the first time."

Dougherty and Hope met for the first time shortly after. They reunited a second time when CBS13 got them together to be interviewed for this story.

The two men, face-to-face, shared their stories of Dachau.

"My number, 44249, I just become zero man. A prisoner of war. You are nothing there, zero," said Hope to Dougherty. "Brave American soldiers, when they come, I...," Hope paused, overcome by emotion.

The two men missed each other than day at Dachau as Hope had been forced on the death march by SS guards.

"We were at the satellite camp where he had been for two years. We were there maybe 3 hours and then we leave. But during that window, he is gone," said Dougherty.

Hope told Dougherty how he remembers the fateful moment he and the other prisoners knew they were free.

"There comes American tanks. One after another, hundreds of them. We say, 'hooray.' I can't explain. Everybody dancing, some praying, some crying, we are free. We are free. Thank you. Thank you," said Hope through tears to Dougherty.

Dougherty turns 99 this year and Hope turns 100.

Their story serves as an important reminder that there are few people still alive today who can give firsthand accounts of this chapter of history -- and there is little time left to share them.

Earlier this year, the Hope family began rallying the community and raising money to support Nick's trip back to Dachau.

They say they are keeping the fundraiser going, wishing now to raise money to support Hope publishing a book on his life story.