Historic Berkeley rezoning vote delayed amid fiery debate

The room was packed Tuesday as attendees anxiously awaited the sole item on the special Berkeley City Council agenda: a large rezoning proposal to allow denser housing throughout the city.

But that excitement was cut short when planning staff revealed that they missed a critical state requirement for the proposed changes, pushing a final vote to the fall at the earliest. Under California Senate Bill 18, cities must provide ample notice to the appropriate indigenous tribes as well as the opportunity for consultation on changes to the general plan -- such as those proposed under the rezoning item before the Berkeley City Council.

Planning and Development Department director Jordan Klein estimated that between staff time and consultants, the cost of the rezoning item is already approaching $750,000.

"We really regret any delay that might be caused as a result," Klein said.

Instead, the council voted unanimously on a set of guidelines for planning staff to work into a revised ordinance -- revisions that could take months to complete, pending the required tribal consultation and a forthcoming evacuation study for high fire risk areas of the Berkeley hills.

The small apartment-style housing goes by many names -- such as "gentle density" and "missing middle" -- but several speakers in the council chambers also described it as a gentrifying force that would endanger the fire-prone neighborhoods of the Berkeley hills.

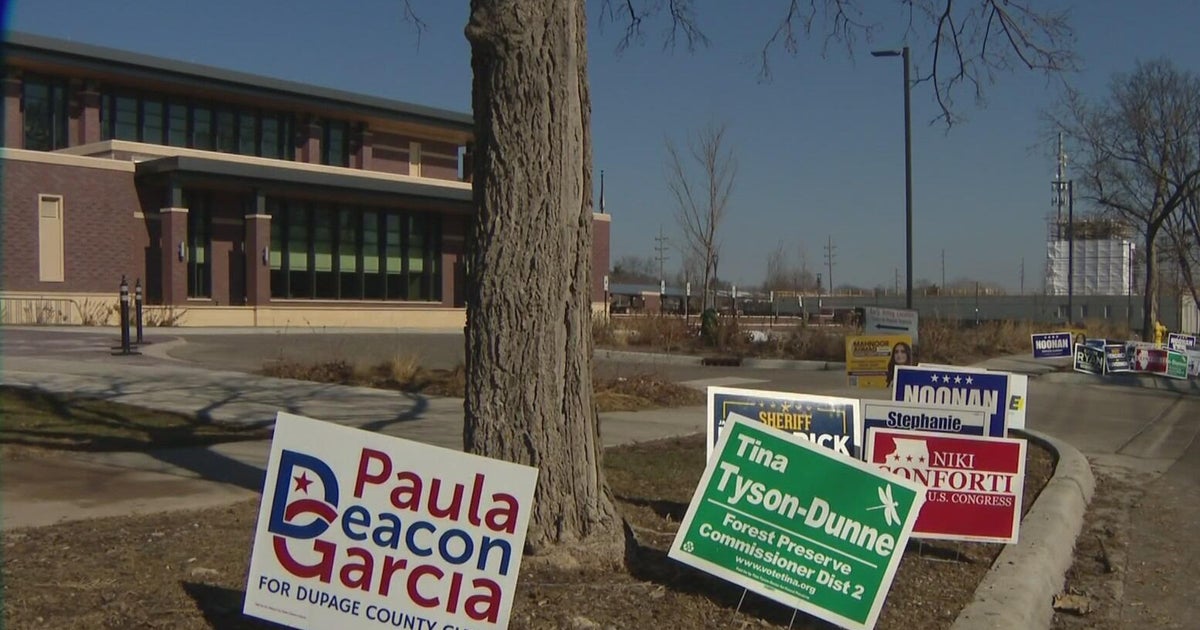

Under the proposed ordinance from planning staff, several low-density zoning districts would be rezoned to encourage multi-unit housing -- including in the Berkeley hills -- in the hopes of easing the housing crisis.

"This is one of the most ambitious rezoning efforts of any city in the United States, and I think it's appropriate that it starts here in Berkeley," Berkeley Mayor Jesse Arreguin said.

Several council members and public commenters expressed hope that the proposed changes would make progress toward undoing Berkeley's legacy as the first city to enforce single-family zoning. In 1916, the Elmwood neighborhood adopted exclusionary zoning rules to prevent a Black-owned dance hall from moving in.

Councilmember Mark Humbert, whose district included the Elmwood neighborhood, said the zoning category was "formed in a crucible of racism."

"As council member for District 8, I feel I have a historic obligation to fix this," Humbert said.

Humbert also recognized the efforts of former councilmember Lori Droste who previously represented District 8. During her tenure on the council, Droste introduced legislation calling for an end to single-family zoning throughout the city.

While that measure passed unanimously in December 2022, it may still be several more months before the council can take substantive action and pass the middle housing ordinance.

"This is Berkeley's best chance to create homes for middle and moderate-income people like teachers, firefighters, seniors, and kids who grew up here," Droste wrote in a post on X.

In addition to Droste, state Sen. Nancy Skinner and Assemblymember Buffy Wicks also sent letters urging the City Council to pass the ordinance.

But changes to zoning in the hills were a sticking point for many public commenters, as well as Vice Mayor Susan Wengraf and Councilmember Sophie Hahn, who is also running for mayor this year.

Both represent portions of the Berkeley hills and raised concerns that additional density would make it harder for residents to evacuate in the case of a wildfire.

However, a representative of the California Housing Defense Fund -- an organization that takes legal action against cities for failing to comply with housing laws -- argued that increased density in the hills would mitigate the risks of wildfire spread because new developments would fall under fire-resistant codes, unlike many of the Berkeley hills homes that were built decades ago.

The Berkeley Fire Department is currently conducting an evacuation study on the impact of additional density, and the council agreed Tuesday to hold off on any action in the hillside zone until its completion.

What eventually passed unanimously was a motion from Arreguin and Councilmember Rashi Kesarwani that introduced maximum density standards and some tweaks to the planning staff recommendation.

The motion provides direction for planning staff when they come back with a revised ordinance in a few months.

Despite no final vote taking place Tuesday, dozens of speakers in person and on Zoom spoke out in support and opposition to the proposed changes.

Public commenters were largely divided on the middle housing issue along age and homeownership: older Berkeley homeowners tended to oppose the measure, while younger renters tended to support it.

"We have land acknowledgments, we have BLM signs, but we're not sure if we're actually going to turn any of that into policy," said one commenter, who was speaking in support of the housing proposal.

"Are they going to put apartment buildings on our front lawn?" asked Renata Polt. She and her husband have lived in the same home in the Berkeley hills for more than 50 years.

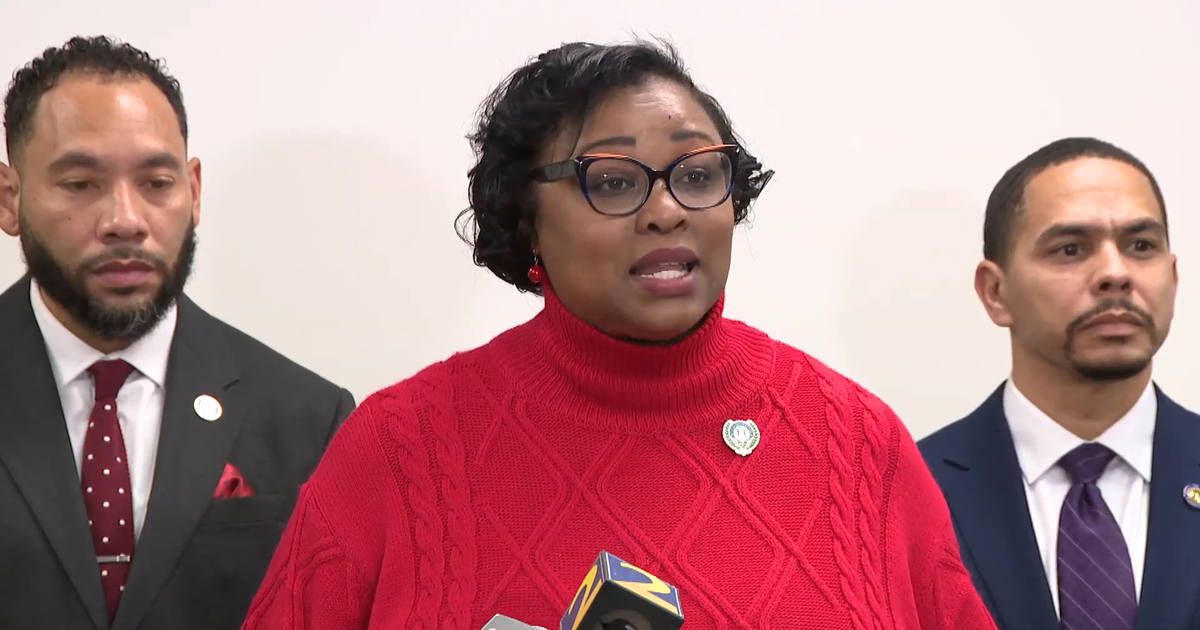

"This is a necessary function to open the doors of opportunity for young people, young families city workers, and everyone in between. That's the missing middle," said city council member Ben Bartlett, who supports the change. He says allowing higher density housing across the city will open up neighborhoods once only available for the wealthy and simply add more housing supply.

"All these young people and young families coming up have nowhere to live. Our city workers have nowhere to live near the city," said Bartlett.

"This is really about the chance to give everyone an opportunity to live in the highest resourced areas that we have," said Jordan Grimes of the Greenbelt Alliance.

"It provides a road map for other communities to build off of, to start to knock down these walls of exclusion that we have built up over decades," he continued.

Some local homeowners, however, remain skeptical.

"Everybody gets to buy a $100,000 house in this neighborhood? Obviously that's not going to happen," Polt said.

Residents have also expressed concern about fire risk. The city council is working with the fire department and city staff to do an evacuation study, and could exclude some of the highest risk areas from additional density.