Experimental Therapy Gives Children With Genetic Disorders A New Chance At Life

by Juliette Goodrich and Molly McCrea

SAN FRANCISCO (KPIX 5) -- Imagine giving birth to what appears to be a healthy baby, only to discover your newborn has a devastating disease and will have to fight every day to stay alive.

While these children and their families would have faced grim prospects in the past, today an experimental gene therapy is giving them a new chance in life.

The landmark clinical trial for the therapy recently happened at UCSF Benioff Children's Hospital at Mission Bay in San Francisco. Inside, doctors performed six daring, complex brain surgeries on six children -- ranging in age from 5 to 9 -- with life-changing results.

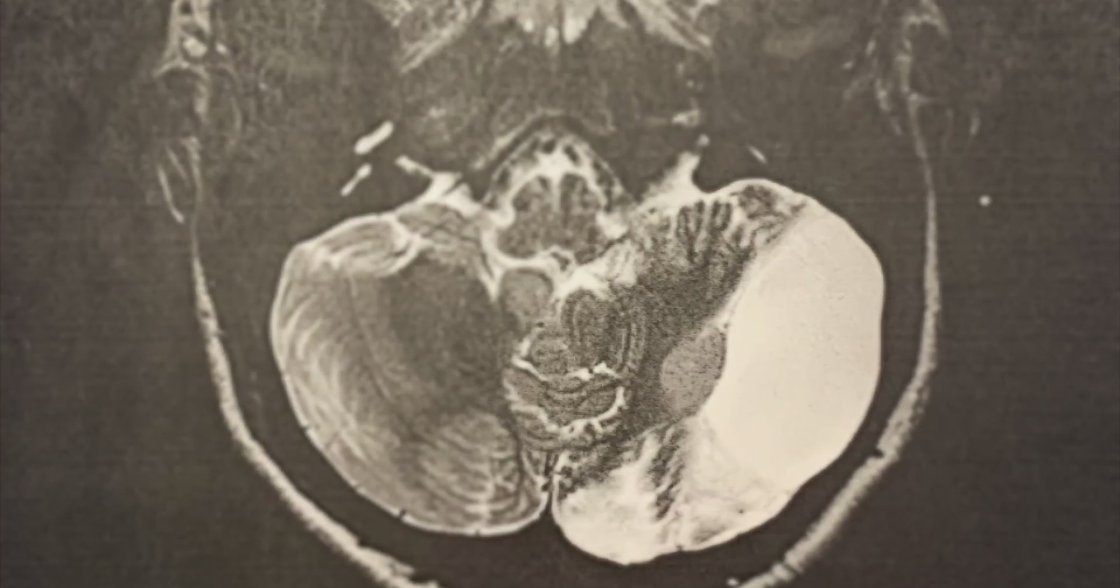

The trial unfolded inside a specially designed hybrid operating room that combines an innovative surgical theater with an MRI. The neurosurgeons allowed KPIX 5 to go into the hybrid room to see the remarkable technology first hand.

In the specialized room, a team of doctors conducted the trial as a small number of parents took a giant leap of faith.

"We are really lucky to have this. And we have to take the chance," explained Ashlee Lo, the mother of 6-year-old Alex.

Three of the six families spoke to KPIX 5. They all expressed their deep desire to help their kids.

"I was wondering, you know, is it something they can do for my daughter?" said Kaili Qu, remembering what she thought when she first heard of the therapy for her 9-year-old daughter Sellina.

"To be able to provide for her what she wants or what she needs," remarked Albert Lou as he held his 7-year-old daughter Audrey's hand.

In each family, there is a child who was born with a defective gene that causes an extremely rare disorder.

The inherited problem is so rare, only about 100 cases have been documented in the scientific literature. Roughly 25 cases have been identified in Asia, but experts explain it impact all races and ethnicities.

The disorder is called AADC deficiency. "AADC" stands for "aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase."

In children who have inherited the defective gene that leads to AADC deficiency, they are unable to make an enzyme that creates critical neurotransmitters.

These neurotransmitters include dopamine, norepinephrine, epinephrine, and serotonin. These neurotransmitters are important for motion and cognition. The disability leaves the children locked in their bodies. Severe cases can lead to premature death within the first 7 years of life. These children suffer from severe developmental delays.

"They cannot walk, they cannot talk, they cannot feed themselves and as a result, they require lifelong care," explained Dr. Nalin Gupta. Dr. Gupta is chief of pediatric neurosurgery at UCSF Benioff Children's Hospital and involved in the trial.

The children have no muscle tone. The children have no ability to control any of their body parts. They can't lift up their heads, or sit up on their own.

"If you pick him up, it feels like you're picking up a pile of Jell-O. He kind of falls between your arms," explained Alex's father James Lo.

Catching a cold can kill them. They are unable to cough up any mucus. The winter months are perilous.

"She was checked into the hospital nearly every single month," said Carrie She who is Audrey's mom.

They suffer painful involuntary movements that can last for hours. The condition is known as an "oculogyric crisis." This event is characterized by the eyes deviating extremely upward, laterally or downward where they remained fixed and causes pain. It is extremely frightening for family members.

"It's heartbreaking to see these children being affected by this disease.' remarked Dr. Krystof Bankiewicz. Dr. Bankiewicz is a neurologist who holds many titles at UCSF as well as numerous patents that focus on powerful new approaches to treating brain diseases.

He explained because these children can't make important neurotransmitters, they barely sleep. That means the parents are severely sleep deprived as well

"20 minutes to 2 hours that's all," said Ashlee Lo, describing the longest her son Alex sleeps at night.

Sellina's mom Kaili explained how her daughter was always yawning and looked perpetually exhausted. "She mostly sleeps in the early morning, like 3 AM, but then the slightest sound wakes here up. Her sleep is very light," remarked Kaili.

Because AADC deficiency is so rare, there is limited clinical expertise and virtually no industry incentive to develop any treatments. But now, there's an experimental therapy.

"We just feel like we are very fortunate," said Alex's dad James.

These parents are all internet savvy, and found out about the trial online. They gleaned valuable information from the AADC Research Trust which is based in the United Kingdom. The trust is a charity organization that is dedicated to helping these children and their families. The trust has identified 130 children in 26 different countries who have been correctly diagnosed with AADC deficiency.

KPIX 5 discovered how these parents had been tracking the progress of the Bankiewicz lab for years. The lab team had already deployed an innovative approach to deliver a gene therapy to Parkinson's patient with long-lasting results. They understood how Dr. Bankiewicz and his team would soon attempt the similar approach with children suffering from this ultra-rare disease.

Once the FDA gave UCSF permission to proceed with the clinical trial, these families monitored, and jumped on board.

"They're really pioneering this," remarked Dr. Bankiewicz.

Dr. Bankiewicz developed a way to replace the defective gene in these children by delivering millions of healthy copies deep into the child's brain.

These good genes are tucked inside a disabled virus.

"So sort of like a Trojan Horse," remarked Dr. Bankiewicz.

The virus slips into the brain cells and is then able to deliver the good genes.

"We have to be very clever to do it in a way that doesn't damage other cells," explained Dr. Gupta.

In the trial, the neurosurgeon needed to first drill a small hole into each child's skull.

Using a sophisticated MRI, and special software, Dr. Gupta watched as he navigated a fine hollow needle thru the small hole to the exact right spot in the brain. Then thru the hollow needle, the gene therapy was delivered.

"Then we actually infuse a solution that contains the virus and the corrected gene," said Dr. Gupta.

As to the benefit? KPIX 5 saw all the children after their surgeries, and the results were astounding.

All the children can now sit up on their own, and lift their heads. Their painful attacks have disappeared. And they all sleep better.

"It was a great surprise," exclaimed Alex's dad James.

Alex now interacts with his family. In fact, for the first time, there is sibling rivalry. He notices when his little sister Claire gets attention from mother and will express displeasure. The brother and sister are now learning more about each other. His mother is thrilled.

"We're really blessed and so fortunate," said Alex's mom Ashlee.

It is now clear that Sellina understands both Mandarin and English. For the first time, she can go to school.

KPIX 5 asked Sellina if she liked going to classes and she responded in the affirmative.

Sellina was the first out to get out of her wheelchair, and try to walk. The neuroscientists were astounded and pleased.

Audrey is also determined to get places. She most recently tried out a walker. She is swimming, kicking thru the water, and holding her head up.

Audrey is also practicing how to eat and swallow. Prior to the gene therapy, these children were all fed through a gastronomy tube, where a tube is inserted through the abdomen and nutrition enters the stomach directly.

"It's just amazing that we're living in this era: technology and science! We're very grateful and thankful," exclaimed Audrey's father Albert Lou.

The scientists are grateful for the families, and the families are grateful their children now have a new chance at life.

"A new start ... a new start," said Audrey's mom Carrie Shi.

"Yes, yes, it's a new life," remarked Sellina's mom Kaili.

"He's really, really happy," said Alex's mom Ashlee.

"What I'm hoping for is that we get other leaps in the future," said Audrey's dad Albert Lou.

UCSF is now continuing the trial with other children, with the blessings of the FDA.

The treatment has the potential to set the standard to treat other neurological diseases caused by a single gene defect.

Links:

UCSF Benioff Children's Hospital

AADC Deficiency Clinical Trial at UCSF