California Lawmakers Creating Policy To Target Child Prostitution

Part two in a three-part series on Alameda County's fight against child prostitution

OAKLAND (BCN) - For state Assemblyman Sandre Swanson, ending the selling of young girls for sex on the streets of Alameda County is personal.

The Democratic lawmaker was born and raised in West and North Oakland and rented his first apartment in East Oakland.

He said he has witnessed prostitution in the city for years.

"We can't just continue to drive by and see young people on the corner," he said. "We have to embark upon a rescue mission."

Swanson, D-Alameda, has therefore made it a legislative priority to combat human trafficking in general and commercial sexual exploitation of children—an especially odious and increasingly prevalent form of trafficking—in particular.

California lacks a unified response to human trafficking, but Swanson is one of several Bay Area officials making inroads in protecting exploited children and prosecuting their attackers.

Series Part 1: Officers Struggle To Keep Pace With Prostitution

Series Part 3: County Grapples With Best Way To Rescue Teens

AB 499, introduced by Swanson and signed into law in 2008, established a pilot program in Alameda County that directed minors arrested for prostitution away from criminal prosecution and into recovery programs.

AB 17, also by Swanson, was passed in 2009 and built upon the state's 2005 Trafficking Victims Protection Act by increasing fines against anyone convicted of pimping minors.

But despite these and other successes, those fighting trafficking in California still face lax state sentencing laws, ambiguous legal language and the challenge of taking on nuisance businesses that foster prostitution.

A bill sponsored by Swanson would automatically classify the pimping of minors as a form of trafficking under state law, as it is classified under federal law. The bill stalled last year before finally making it through the Assembly in late June. It goes before the state Senate appropriations committee this month.

Legal And Legislative Victories

Alameda County first began recognizing commercial sexual exploitation of children as a serious problem in the early 2000s, according to Barbara Loza-Muriera, a facilitator with the county's Interagency Children's Policy Council and program specialist with its Sexually Exploited Minors Network.

The juvenile court's presiding judge at the time, Brenda Harbin-Forte, was part of the children's policy council executive committee and was the first to raise the issue with the group, Loza-Muriera said.

She said Harbin-Forte was noticing that when she looked more closely at many young girls who came before her facing shoplifting or drug charges, she found that they were prostitutes.

Sure enough, Loza-Muriera said, law enforcement and social workers were also dealing with the problem, even though it hadn't been identified as a prevalent issue up to that point.

"Juvenile justice people put things in categories, but this permeated everything," Loza-Muriera said. "Truancy, stealing. It was a forest-and-the-trees kind of thing."

The county quickly established a task force for dealing with commercial sexual exploitation of children and never looked back, she said. The group spent almost a year homing in on what they perceived as the two most pressing issues: the crime itself and the need to focus on sexual exploitation directly instead of peripherally.

County officials identify about 200 new sexually exploited children annually and case manage another 120 from previous years, Loza-Muriera said.

Anti-trafficking laws are derived from the U.S. Constitution's 13th Amendment, which states that "neither slavery nor involuntary servitude" shall exist in the U.S. except as punishment for a crime.

Prosecutors, however, didn't have any federal statutes or sentencing laws to attack human trafficking—defined by the United Nations as "the acquisition of people by improper means such as force, fraud or deception, with the aim of exploiting them"—until Congress passed the federal Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000.

State lawmakers followed suit in 2005 when they added trafficking, the state's first new crime category since 1999, to California's penal code.

But human trafficking is a broad classification, and most trafficking involves immigrants and forced labor, according to the U.S. Department of Justice. Domestic sex trafficking, particularly of minors, is not as widely acknowledged or understood, activists say.

Sharmin Bock, a deputy district attorney from Alameda County who is now running for district attorney in San Francisco, prosecuted the state's first human trafficking case and has been working with Swanson to change the language of California's penal code to reflect the reality of commercial sexual exploitation of minors.

She said the problem has reached epidemic proportions in Alameda County as the law slowly changes to take into account the emotional manipulation and psychological terror that pimps use to control the girls, many of whom start as young as 12 or 13.

"Children don't identify as victims because they're still under the coercive effect of their traffickers," she said.

Prosecuting the pimps therefore requires convincing the girls to cooperate with police and showing jurors that the girls are victims, even if their trauma is not visible on the surface.

Police and prosecutors describe two types of pimps: "guerilla pimps," who physically force girls to sell their bodies, and "Romeo pimps," who foster emotional ties to the girls and act as though they're in romantic relationships.

The Romeo pimps, who are much more common, start out slowly, gaining the girls' trust before asking them to turn just a few tricks to help pay the rent or finance a trip together, according to Loza-Muriera. They expose the girls to violence and implicitly threaten them before finally making overt demands.

The girls, most of whom come from broken homes or unstable upbringings, believe they're in legitimate relationships. They say they're in love with the pimps even though they're terrified of them.

"Despite what has occurred, one of the greatest challenges is ensuring the child is on the train when the train pulls into the courtroom," Bock said.

As it currently reads, California's penal code requires that "force, fraud or coercion" be demonstrated to prove that an individual has been a victim of trafficking.

But Bock and Swanson want to amend the language to conform with federal law, which says any commercial sexual exploitation of a minor is automatically classified as human trafficking.

"It would ensure California children receive the same protections under state law as federal law," Bock said.

Swanson introduced AB 2319 in 2010 to amend the Penal Code, but it stalled in the appropriations committee because of budget concerns.

Adding trafficking charges to convictions leads to more prison time, which costs the state more money, Swanson spokeswoman Amy Alley explained.

Most of the 2010 bills that would have cost money were held indefinitely, so Swanson reintroduced the bill as AB 90 earlier this year, Alley said. It passed the state Assembly on June 27. The bill goes before the Senate appropriations committee on Aug. 15.

"It's a very good bill, and we will not stop this campaign," Swanson said. "I'm prepared to introduce it next year if that becomes necessary, but we cannot stop. We have to show zero tolerance."

Statewide Shortcomings

Another common criticism of the California Trafficking Victims Protection Act is its sentencing guidelines, said Kathleen Kim, a professor at Loyola of Los Angeles Law School. Kim started one of the Bay Area's first legal aid programs for victims of human trafficking, the Human Trafficking Project, in 2002.

She also helped write the trafficking victims protection act and served on a state task force established under the legislation.

Maximum punishments for traffickers on a federal level are in the 20-year range, but state law allows a maximum of five years in prison for trafficking an adult and eight years in prison for trafficking a minor. Politics drove that decision, Kim said.

"For the state legislation there was a lot of advocacy involved," she said. "We wanted to be able to pass the anti-trafficking act with the least resistance and most support across all sectors."

Higher penalties would have resulted in pushback from the California Public Defenders Association, she said.

Police and district attorneys therefore work hard to pile on the charges and build a case that can garner a lengthier prison term, said Sgt. Holly Joshi, a spokeswoman for the Oakland Police Department who spent three years with the vice and child exploitation unit.

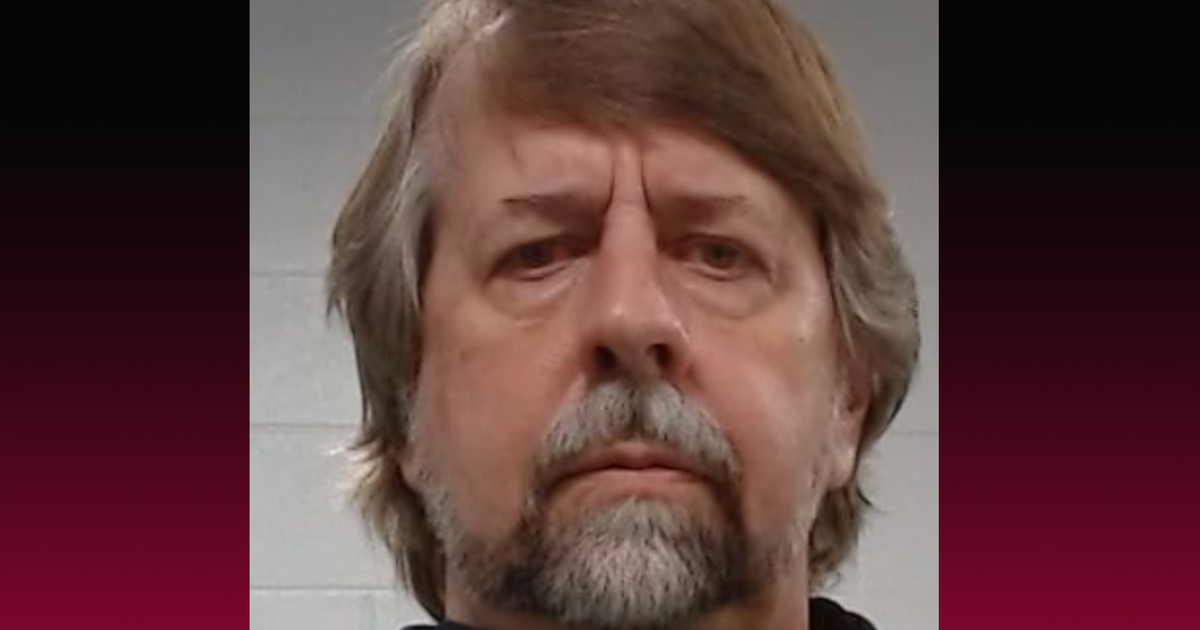

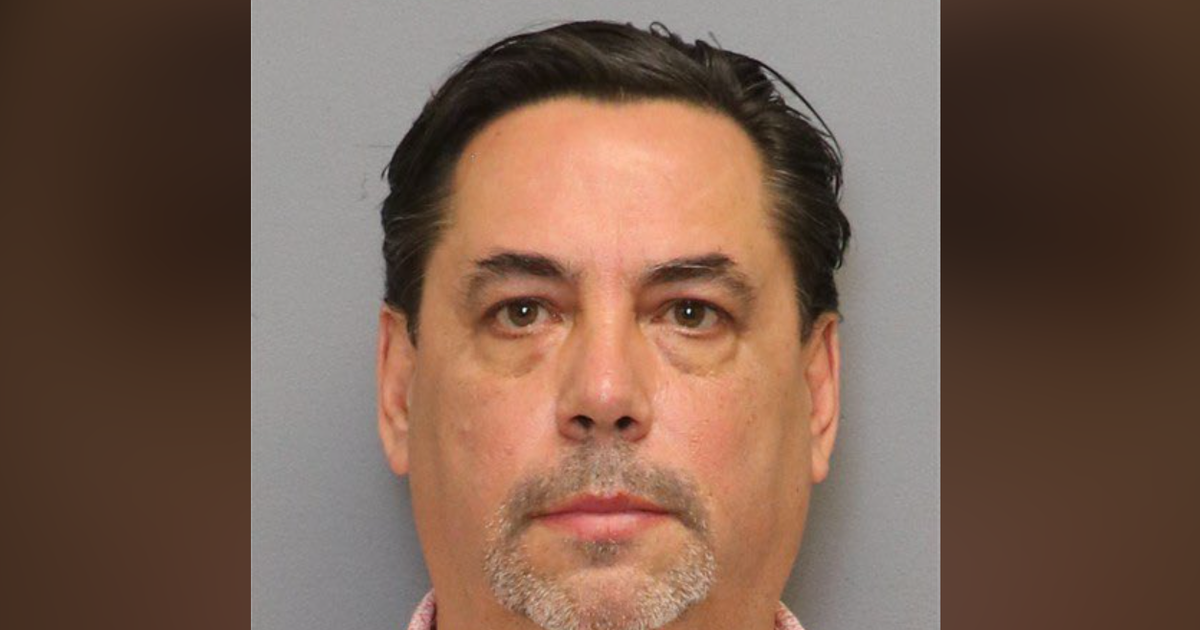

A drab hallway in the Police Department's headquarters on Seventh Street leads to a cluster of cubicles that comprise the four-person vice and child exploitation unit. One of the outside walls is adorned with a "wall of shame" featuring photos of the more than 100 men—and a few women—the team has put behind bars.

Captions on the photos list their subjects' sentences: 235 years, 240 years.

Facilitating underage sex with a client, known as a "John," constitutes a lewd act on a child, which requires registration as a sex offender, Joshi said. False imprisonment, statutory rape, child pornography, and other related charges are not uncommon.

Pimping and pandering are also separate felony charges; pimping is defined as living off the earnings of a prostitute, while pandering refers to facilitating prostitution or recruiting prostitutes.

Police take statements from the girls and use physical and electronic evidence such as Internet postings and cellphone records to build their cases.

The Internet presents both challenges and opportunities for police, Joshi said.

"The moment they post a photo of a child online it's child porn," she said. "Often that makes the FBI get involved. Once you start posting on different sites it can easily become an interstate commerce thing."

According to Kim, the more pressing problem with the state's response to human trafficking is therefore not the sentencing laws, but the absence of a unified state response.

The California Trafficking Victims Protection Act established a statewide task force, but the group disbanded in 2007 after issuing a 128-page report containing non-binding recommendations.

The state attorney general's Crime and Violence Prevention Center was then disbanded in 2008 because of California's budget crisis, which essentially ended coordinated statewide efforts to address human trafficking.

Although the 2007 task force recommended that the state Department of Justice work with the California Health and Human Services Agency to document human trafficking, no such databases have been created.

Trafficking arrests are not included in reported crime data, and the only data collected about victims pertains to homicide, according to the justice department.

Kim served on the state's 2007 task force and said that although many individual jurisdictions are committed to weeding out trafficking, her time with the state committee showed her the benefits of a broader coalition.

"It really brought together a diverse array of perspectives, all from stakeholders," she said. "It was actually really fundamental to a more sophisticated understanding of the problem."

A statewide task force could resemble a steering or advisory committee used to put knowledge into implementation, she said. It would facilitate the sharing of research about cases and ideas for collaborating with the federal government.

"I think it could be used to inform each other of what different localities are doing," she said. "Also for cross-training purposes."

Multi-jurisdictional communication is also important because many pimps take their girls outside the state or to other localities, said Oakland police Officer Jim Saleda, acting sergeant of the department's vice and child exploitation unit.

For instance, some local pimps take the girls to U.S. Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton in San Diego twice a month, as well as to cities hosting All-Star games and national championships, Saleda said. Reno, Las Vegas and Phoenix seem to be popular destinations, he said.

Nuisance Businesses

Local municipalities aren't waiting for the state to take action, though. In Oakland, several lawsuits have been brought against businesses that the city claims foster prostitution, particularly sexual exploitation of minors.

The Oakland City Attorney's Office filed suits in December against three motels under the state's Red Light Abatement Act, which lets cities sue to close nuisance businesses and collect civil penalties and other damages.

According to the suits, the Economy Inn at 122 E. 12th St.; Sage Motel at 4844 MacArthur Blvd.; and National Lodge at 1711 International Blvd. are known places of prostitution, which the suit alleges management has knowingly allowed to continue.

The allegations made against the Economy Inn, located along a section of Oakland's International Boulevard commonly called the "Track" because of the prevalence of prostitution there, are particularly egregious.

The suit alleges that on March 16, 2008, a John raped a 17-year-old prostitute near the motel. Less than a month later, the suit states, a minister helping a prostitute escape her pimp was shot by the pimp in the motel parking lot.

The lawsuit also describes an incident on June 27, 2010, in which officers rescued a 16-year-old girl who was kidnapped, taken to the Economy Inn, and forced into prostitution by a pimp working out of the motel.

A month later, a 14-year-old girl was raped by two men—apparently the attack was orchestrated by two pimps trying to indoctrinate the girl into the sex trade, according to the suit.

That August, a man was arrested in a room with two 14-year-old girls who police believe the man was pimping out.

The lawsuit alleges that the motel has been a haven for "guerilla pimps" who use violence to keep their prostitutes in line, including one kidnapped out of Sacramento in August 2010 and one taken from San Diego in October.

The pimps raped and beat the women in addition to forcing them to work as prostitutes, the suit says.

The Economy Inn did not return calls seeking comment.

No less notorious to the Oakland Police Department is the National Lodge, also located on the Track about five blocks from the Economy Inn.

"A male undercover officer can drive into the National Lodge parking lot and honk, and girls come out," said Officer Hamann Nguyen with the vice and child exploitation unit.

Mike Patel, the motel's owner and manager, said he takes care of his property but can't control what happens on the street outside.

He said the men who bring girls to the motel are not registered there.

"When I see them I kick them out," he said. "I call the police. But I can do nothing when they're outside."

Some neighbors, however, are not convinced. Jody Terrazas raised two daughters a couple of blocks from the motel and owns a business nearby.

She said prostitution activity has fluctuated during the 40 years she and her husband have lived in the neighborhood, but that it has been a glaring problem ever since the National Lodge opened.

The sex trade is now on full view in the streets, she said.

"It's really tough," she said. "It affects us all."

She said she raised her girls, now 32 and 33 years old, in a cloistered environment because there are turf wars among pimps on the streets.

Several months ago, rival pimps started firing shots at each other near International Boulevard and 18th Avenue, Terrazas said. A pimp and a prostitute were hit while sitting in the pimp's car.

The pimp then opened the door and kicked the injured girl onto the street before driving off, Terrazas said.

Neighborhood girls are also mistaken for prostitutes, and young boys are susceptible to being caught up in the trade, she said.

Mili Bolanos, a spokeswoman with Oakland Community Organizations, said that's why residents have decided they've had enough.

Members of the community have marched down International Boulevard several times this spring and summer to fight the prostitution, she said.

Police Chief Anthony Batts and Mayor Jean Quan have attended some of the "Safe Streets, Safe Kids" rallies, the most recent of which was held on Thursday.

"It's marvelous," Batts said Thursday of the community engagement. "It's exactly what I want to see."

He took over a bullhorn to introduce the officers in charge of the neighborhood and answer questions about police efforts to combat prostitution and human trafficking.

Marchers wore signs that said "Make our neighborhood safe" and "Honk for safe streets, safe kids."

"Part of what's so hard in our neighborhood is that by seeing this our kids are subconsciously thinking it's OK, that it's part of life," Terrazas said.

That is part of why Swanson has committed so much of his legislative career to fighting sexual exploitation, he said.

"I feel that there, but for the grace of God, go I," he said. "I think my purpose in being an elected official is to protect the health, education and safety of these children."

(Copyright 2011 by CBS San Francisco. All Rights Reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.)