California housing crisis: Lawmakers reach deal on bills to boost homebuilding

SACRAMENTO — Facing a housing shortage in the nation's most populous state, California's legislative leaders on Thursday backed a pair of bills that would open up much of the state's commercial land for residential development, bypassing some local zoning laws to replace shuttered shops with affordable apartments.

California doesn't have enough places for people to live. It's among the reasons why rents are high, homes often cost more than $800,000 and on any given night more than 100,000 people are sleeping on the streets.

To make up the shortfall, state officials say California needs to build about 310,000 new housing units per year over the next eight years — more than two-and-a-half times the number the state normally builds each year.

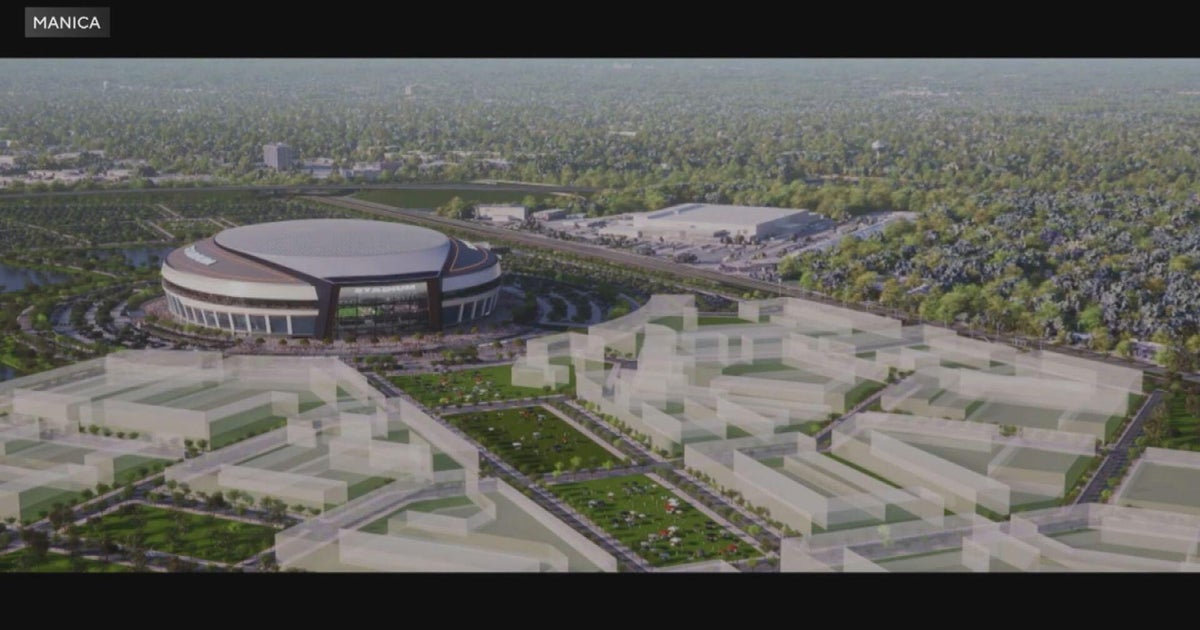

One popular idea is to build housing on commercial land, especially since lots of retailers have closed in recent years as shoppers moved their purchases online while some office buildings sit empty after companies adopted work-from-home schedules during the pandemic.

But to do that, developers first need permission from local governments. Local leaders often don't want to let housing be built on land that's been set aside for commercial use because they get more money in property taxes from stores than homes. When a store closes, some local governments are content to leave the land idle, sometimes for decades, hoping another retailer will replace it.

On Thursday, state lawmakers and labor leaders announced they would back two bills to change that. One bill known as AB2011 would let homebuilders bypass the local approval process and build housing on some commercial land if a certain percentage of the homes they build are affordable. A separate bill known as SB6 would let developers build market-rate housing on commercial land, but remain subject to a local approval process.

Assemblymember Buffy Wicks, a Democrat who authored the affordable housing bill, said the two bills would create "millions" of units of new housing.

"I think these two bills, taken together, represent transformative housing policy in California," Wicks said.

The biggest obstacles for the bills has been figuring out who would build the housing. Labor unions, powerful supporters of the Democrats who dominate the state Legislature, have been pushing for legislation to require a "skilled and trained" workforce, meaning a certain percentage of laborers have taken a state-approved apprenticeship program. But affordable housing developers say there often aren't enough workers available to meet that standard, which makes projects difficult to complete.

The solution was to give homebuilders a choice. The bill that requires affordable housing does not require a skilled and trained workforce, while the bill that does not require affordable housing does require it. Ray Pearl, executive director of the California Housing Consortium, called it "the first legislation in years that has brought together affordable housing providers and labor."

"Everybody wanted their way or the highway," said state Sen. Anna Caballero, a Democrat and author of the market-rate housing bill. "We were able to craft a solution where there is something for somebody in one of the two bills."

While lawmakers have overcome labor union opposition, they could still face resistance from local governments, who argue it's not fair to disregard community decisions about land use. A spokesperson for the League of California Cities said Thursday the group was still reviewing the proposals and could not comment.

California's top legislative leaders, Senate President Pro Tempore Toni Atkins and Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon, both praised the legislation, with Atkins calling it a "monumental legislative achievement."

"We didn't go into this to have one side win at the expense of another. As a result, we have a housing victory that checks off a lot of the boxes – affordability, mixed-use, transit accessibility and labor security," Rendon said.