To Help Fight Vaping, Schools Look To Their Own Students

(CNN) -- Teen vaping is on the rise, and schools are searching for solutions, with some taking disciplinary action or installing vape detectors in bathrooms.

Still, the problem has continued to swell. The US Food and Drug Administration announced in November that vaping had increased nearly 80% among high schoolers and 50% among middle schoolers since the year before. The resignation announcement of the agency's commissioner -- Dr. Scott Gottlieb, who vowed to crack down on what he described as an "epidemic" of teen vaping -- has only added to the uncertainty over what's to come.

But many schools can't afford to wait, and some are turning to what may be an untapped resource: their own students.

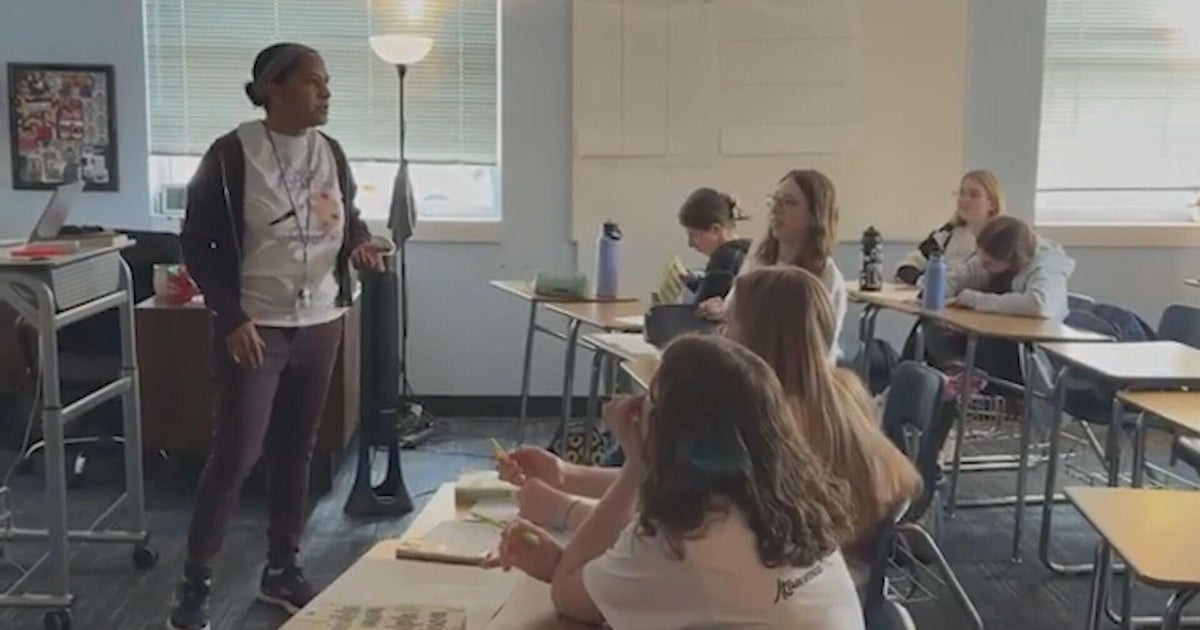

Last month, students from middle and high schools in California's Santa Clara County gathered for a pilot program designed to teach them about the potential dangers of vaping and how to deliver that message to their fellow students -- and how to resist peer pressure that experts say has contributed to students' vaping.

"When [the message] comes from an adult, it sounds so antagonistic but also like they don't understand us," said one attendee, 17-year-old Selena.

"But I think when it's coming from a friend," she added, "I feel like it means much more to the person receiving it."

Selena said she has increasingly recognized signs, often subtle at first, that her friends were vaping -- like when someone develops a cough or unusual mood changes. It's even changed the dynamics of her friend group. She feels like people her age might spot the problem more easily than many adults.

"I saw that my friends who did have devices literally had an addiction," she said. "And it was sad to watch."

Experts worry that the devices could put kids' developing brains at risk, get them hooked on nicotine early in life and be a gateway to smoking and other drugs. But the long-term effects aren't clear.

The Santa Clara County Office of Education has received "tons of calls" about vaping on school campuses, according to Sonia Gutierrez, a supervisor with the office's Safe and Healthy Schools Department. So it decided to take this different approach, working with the county public health department and Stanford University to give the students tools to find creative ways to say no, engage in public speaking and articulate to their peers the dangers and misperceptions surrounding e-cigarettes.

"It's more effective to have students themselves who live in those areas, who go to those schools, who are part of the community to share their voice, share their story and to share why it's harmful," Gutierrez said.

And kids and adults may speak different languages when it comes to a trend like this. According to a show of hands, virtually no students referred to the devices as "e-cigarettes," as the adults did. Many simply call them by the dominant brand, "Juuls."

Tenth-grader Siya, 15, said she signed up for the program because she wanted to learn how to convince other kids about the risks of vaping.

"I already know about all the bad side effects and stuff, but I don't know how to explain that to my fellow peers, exactly," she said.

"I'm scared that the people around me are going to eventually get addicted to tobacco from their addiction of nicotine -- and I don't want that to happen."

'They have a voice'

Peer education programs are far from new, especially when it comes to tobacco. Research has suggested that having students deliver the message and lead sessions can be seen as more fun, that peers can better understanding the problems facing young people and that it tends to be preferred to programs led by teachers.

But experts say you can't just insert an "e" in front of "cigarettes" and expect older programs to work, especially given how the chemistry and technology of vaping has created an entirely new threat to teens' developing brains: devices that have gotten smaller, sweeter and stealthier.

"The most difficult part was staying up to date. We're constantly learning something new about vaping every single day," said Cristina Martins, a health educator with the Southern New Jersey Perinatal Cooperative who piloted a program in three schools last year that trained students to create their own "peer-to-peer education project" in their schools and on social media.

However, one element may carry over from tobacco education programs of yesteryear: a focus on marketing, "so that the young people are aware of the ads that are being used to target them," said Bonnie Halpern-Felsher, founder and executive director of the Stanford Tobacco Prevention Toolkit, which formed the basis for the Santa Clara workshop.

"The vaping industries ... are still using a lot of the same tactics," she said.

Even when it comes to more traditional methods of teaching, experts say time and resources are often lacking to support educating students, parents and teachers about e-cigarettes.

Martins said dozens of schools in New Jersey have called to request information about e-cigarettes since she started giving vaping-focused presentations in early 2017, before launching the peer pilot program. But schools often had only a single day to spare. Some existing materials are split over multiple sessions, and "that specifically didn't work with us at the cooperative," so they made their own.

This includes what is perhaps the largest such curriculum: CATCH My Breath, part of the CATCH Global Foundation, which stands for Coordinated Approach to Child Health. Students who attended its 2016 pilot, which ran in 26 sites in five states, reported that they were less likely to vape, had a new perspective on e-cig ads and shared what they learned with family or friends.

The program's CEO, Duncan Van Dusen, said that a new paper showing the program's effectiveness in vaping prevention is being peer-reviewed. He said the program reached approximately 50,000 students last school year, and in the first half of this school year, that number has multiplied sixfold -- a jump he attributes to the size of the problem and the level of concern among schools and parents.

Although CATCH includes a "peer facilitation component," not all schools implement that part because it "requires a little different classroom management technique," Van Dusen said. It can be tough for schools to find the time of day for health education, enlist someone who can effectively run the sessions, find funding and work with students' extracurriculars.

But, he said, "if you're going to do it right, you can't just say, 'we're going to allocate three hours in this health class.' " Parents and other staffers also need to gain awareness, he added.

Martins agrees that one day isn't enough, but she says that getting people the right information and engaging student clubs is a much-needed start. And the lack of time and resources may be all the more reason to get the kids involved.

"We were just trying to think, what can we do to help the public or teens to start educating each other?" Martins said. "It doesn't just have to be us.

"Empower them. They have a voice."

An important role to play

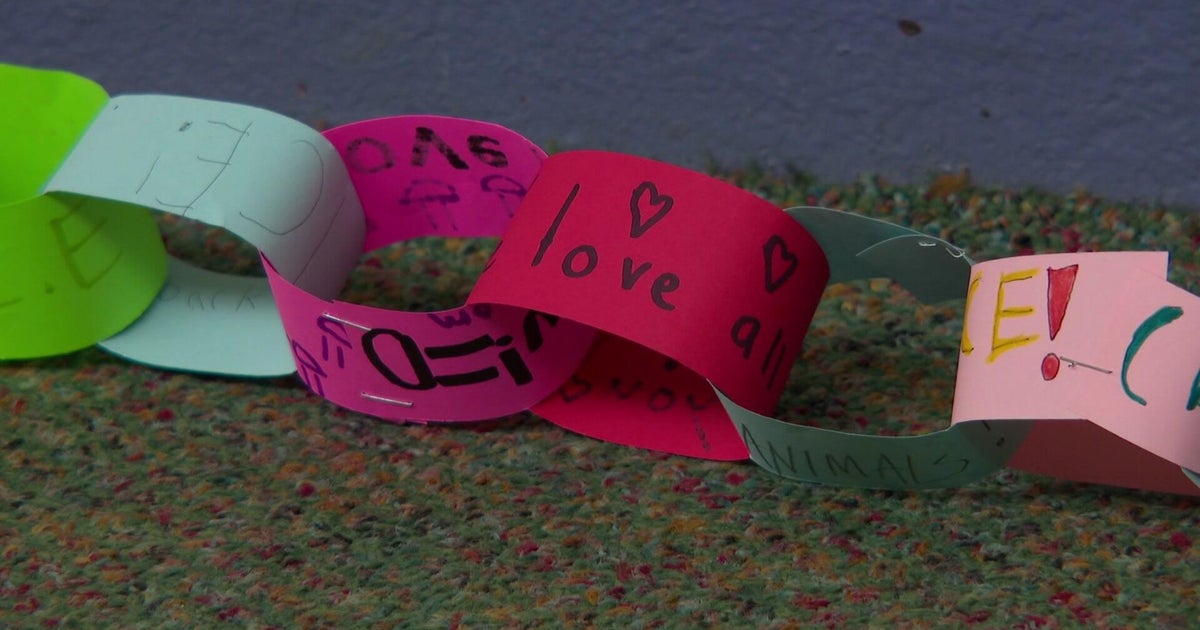

In Santa Clara, toward the end of the day, students clustered into small groups, role-playing what happens when they're approached by other students who vape.

"It's really good. There's nothing in it," one girl cajoled another. "If there's nothing in it, then why are you using it?" the other girl responded, practicing telling her friends how nicotine is addictive.

Some groups modeled "what not to do," playfully mocking or dismissing fellow students who vape.

Experts say that getting kids the right information and forming these skills while they're still young is crucial.

Van Dusen said that CATCH My Breath is adapting a version for upper elementary school students too, where he said reports of vaping are popping up.

"Ninety percent of adult smokers started before age 18," he explained. "If you can prevent a kid from starting to use tobacco, whether it's in the form of a cigarette or in the form of a Juul ... before they walk across that high school stage to get their diploma, then you've substantially cut down the probability that they will ever use nicotine."

For that reason, anti-vaping education tends to focus on prevention, not cessation, but Halpern-Felsher said that doesn't mean students who have started using e-cigarettes are left out. The Stanford toolkit, for example, has been used in detention and after-school programs for kids caught vaping in school, she said.

But this can be tricky, according to Van Dusen, because "the last thing you want to do is make health education a form of punishment." Still, Halpern-Felsher said it's better to offer students help and education than to enforce zero-tolerance policies that expel or suspend students.

"If you get addicted to nicotine at age 15, that's an addiction that's gonna stick with you," said Dr. Sara Cody, health officer for Santa Clara County and director of the public health department. "You're gonna have to work really, really, really hard to shake it."

Echoing some students at the workshop, Cody said teens often think that vapes are harmless, in part because of their sleek designs and pleasant flavors and smells. Halpern-Felsher's own research suggests that the majority of kids who have tried pod-based e-cigarettes started with one that was flavored.

"If you could get a whole new generation of youth addicted to nicotine, that's great for your market," Cody said. "It's really not great for public health."

But kids have a way of putting things in their own words.

"Some kids, they think of it as something cool to do," 12-year-old James said.

"I don't think it's cool. It's weird."

The-CNN-Wire

™ & © 2019 Cable News Network, Inc., a Time Warner Company. All rights reserved.