What's being done to save California salmon as populations continue to decline?

SACRAMENTO - From the Sacramento River to the coast, salmon populations have struggled to survive, and fishing for salmon in California has been canceled for the second season in a row, marking the third season in the state's history a fishing ban has been in place. The heart of the problem: dams and climate change.

Local business impacts

The 2024 season cancelation was announced on April 10, after the Pacific Fishery Management Council (PFMC) acted unanimously to recommend the closure of California's commercial and recreational ocean salmon fisheries through the end of the year, repeating recommendations made in 2023 to close the fisheries.

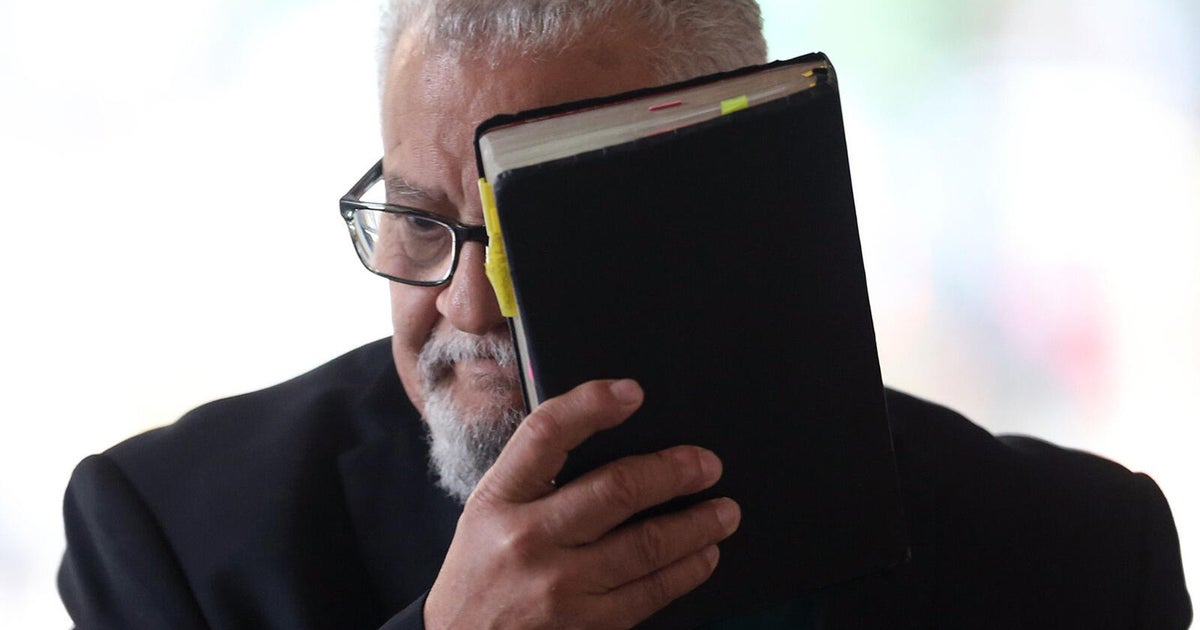

This decision is a blow to salmon industries and fishermen like Rickey Acosta as many struggle to find alternatives.

"Without salmon season we're forced to figure out new species to fish for areas that we are fishing at different times of the year and what it's caused is an effort shift not only for myself but for all of the other boats," Acosta said.

Acosta owns and operates Feeding Frenzy, a sportfishing guide company that takes people out on the waters of the Sacramento River and Pacific Ocean to fish.

He said over the last two years, he's noticed a change in how they can operate and the customers calling to book.

"Sometimes the people just want to go fishing, but majority of the time when it comes to salmon, they want salmon. Essentially, they kind of take their anger out on us like it's our fault and it's not. We're just following the rules and regulations that the state has set for us," Acosta said. "We're just kind of rolling with the punches trying to survive."

He's not alone. His favorite fish stop, Romeo's Bait and Tackle, in Sacramento's Pocket neighborhood also noticed the impact as walls of salmon fishing gear remain untouched.

"They have everything kind of hidden because there's no one coming in to buy salmon gear so a whole salmon display that would normally be probably sold out is just sitting here from the last two years," Acosta said.

Like Acosta, many salmon fishermen have not been able to reel in salmon since the fall of 2022.

"With no salmon season, it's not only taking money out of the economy for the fishing boats the bait shops, hotels and gas stations, but it's taken away the public's opportunity to access to the outdoors and experience fishing for these fish," Acosta said.

The salmon fishing season typically runs from May through October. But this year, those months will stay quiet again.

According to the Golden State Salmon Association, California's salmon industry is valued at $1.4 billion in economic activity and 23,000 jobs annually in a normal season. The season closure of 2023 is estimated to have cost $45 million.

Yet, Acosta, like many others, knows the salmon need help.

"Basically we are trying to do our part as fishermen and conservationists of the outdoors. The fact of the matter is the numbers have just gone down," Acosta said.

NOAA Fisheries has been tracking the salmon decline for decades. They have listed 28 population groups of salmon and steelhead on the West Coast as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act (ESA), to keep them from going extinct.

"Endangered winter-run chinook salmon, for example, on the Sacramento River, there have been a few years recently that we've seen losses of close to 90-95 percent of the eggs in the river because the water is just getting too warm," Michael Milstein, Public Affairs Officer, NOAA Fisheries West Coast Regional Office said.

Milstein said putting the fish on the ESA helps them develop and implement recovery plans for salmon and steelhead listed under the ESA. Taking steps to help populations through habitat restoration and hatchery programs.

He said the Sacramento River historically was one of the biggest salmon rivers on the West Coast, yet changes to the water temperature and river flow have caused populations to dwindle.

"To compare to what we see today. There is just barely a shadow of what they used to be," Milstein said. "There literally were billions of salmon coming up the river. So much so that there were canneries that opened up down toward San Francisco."

The salmon not only threaten the economy but ecosystems if they were to disappear.

"They bring back 10 to 20 pounds of organic material. Nitrogen and carbon that they got in the ocean and that's delivered into the rivers and streams where they spawn then fuel all of the animals and plants that live in and along the streams," said Steve Lindley, director of NOAA's Fisheries Ecology Division at the Southwest Fisheries Science Center.

How the climate is making things worse

Recent years of warming waters and drought influenced by a changing climate have reduced that number to alarmingly low levels, according to Lindley.

"Since about 2012, California has experienced pretty persistent and severe drought conditions and salmon populations have generally been declining over that period. There's been some brief exceptions there in 2017 we had a wetter season and also 2023 that winter was wetter," Lindley said.

Although an improvement, the 2023 season was still canceled. Lindley said it won't be for another few years until they start seeing the record rain and snow year of 2023 pay off.

"Salmon live 3-5 years, so after a string of drought years just a few years after that you'll see the declining salmon population and that's really what we're looking at today," Lindley said. "We know that the more water flowing down the Sacramento River the higher the survival of the juvenile fish can get to the ocean."

In general, the warmer years have outpaced the cooler ones in Northern California. From the rivers to the ocean, NOAA Fisheries has seen the difference between salmon's juvenile stage to their adult stage.

"There's no part of the salmon life cycle that's going untouched by climate change," Milstein said.

The release of cold water from reservoirs can offset warmer years, but this is not a fix-all solution as reservoirs face issues with limited volumes of water due to years of a shrinking snowpack.

According to California's Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA), the fraction of snowmelt runoff that flows into the Sacramento River between April and July has decreased by 8 percent in the past century, with a similar decline seen in the San Joaquin River.

These two areas are the main thoroughfare for Salmon leaving to and from the ocean.

"The recent very low abundances of salmon in the ocean and returning to the rivers like the Sacramento are pretty clearly due to these recent drought conditions stressing those populations," Lindley said.

He said it's not just the water that's up against the salmon, but the land too with the addition of dams and loss of floodplains across Northern California.

"The problem has been 170 years in the making, really since the Gold Rush we've been doing things to the land that we didn't really appreciate would be so bad for salmon. I think now that we are recognizing that fully," Lindley said.

Saving salmon

He said the removal of dams from Oregon to Northern California on the Klamath will help with survival even if drought returns.

"Getting salmon back to places that are most resilient to drought, these high elevation cold areas in the mountains they used to have access to that are blocked by the dams," Lindley said. "The salmon if given access to these quality habitats they can get through these droughts much better than they can down on the valley floor."

Lindley said removing the dams will also help restore natural floodplains and along the Klamath River they may see 400 or more miles of floodplains reopen to the salmon.

"Next year it'll be a free-flowing river, really good habitat for salmon that they have not seen in many decades and this is going to be a really huge boom for California salmon fisheries," Lindley said.

NOAA Fisheries has also been improving work in hatcheries to save salmon for future spawning years.

"It's almost like putting them into a museum. So we know they are going to be there in the future and we can use those fish, too, as the beginnings of rebuilding the population," Milstein said.

They said they have already seen successes in the San Joaquin River from this process.

"There have been a couple hundred thousand juvenile salmon released in the San Joaquin to try to provide that boost to the population. Those fish will swim out to the ocean and hopefully encounter favorable conditions and then will come back up the river and spawn and start to restore that natural population," Milstein said.

What's next

From the state level, all the way down to local fish shops. Everyone now trying to lend a helping hand in hopes more salmon return in the future.

"It's really going to take time. There's no magic bullet to solve the problem. It's just undoing some of this damage and restoring functional ecosystems in rivers and estuaries," Lindley said. "It would just be a tragic thing for California to lose these iconic fish."

After reviewing the PFMC recommendation, the National Marine Fisheries Service is expected to enact the closure, effective in mid-May. This means fishing will remain closed until another season meeting in April 2025.

In addition, the California Fish and Game Commission will consider whether to adopt a closure of inland salmon fisheries at its May 15 meeting.

"My hope is that the state can figure things out, spawn more fish and get more fish swimming out to the ocean and just start over and we all can catch salmon again," Acosta said. "It's all I think about. It's all I want to do. You know we want to go fishing, especially for salmon."