Rain Could Spell Trouble For Calif. Water Conservation

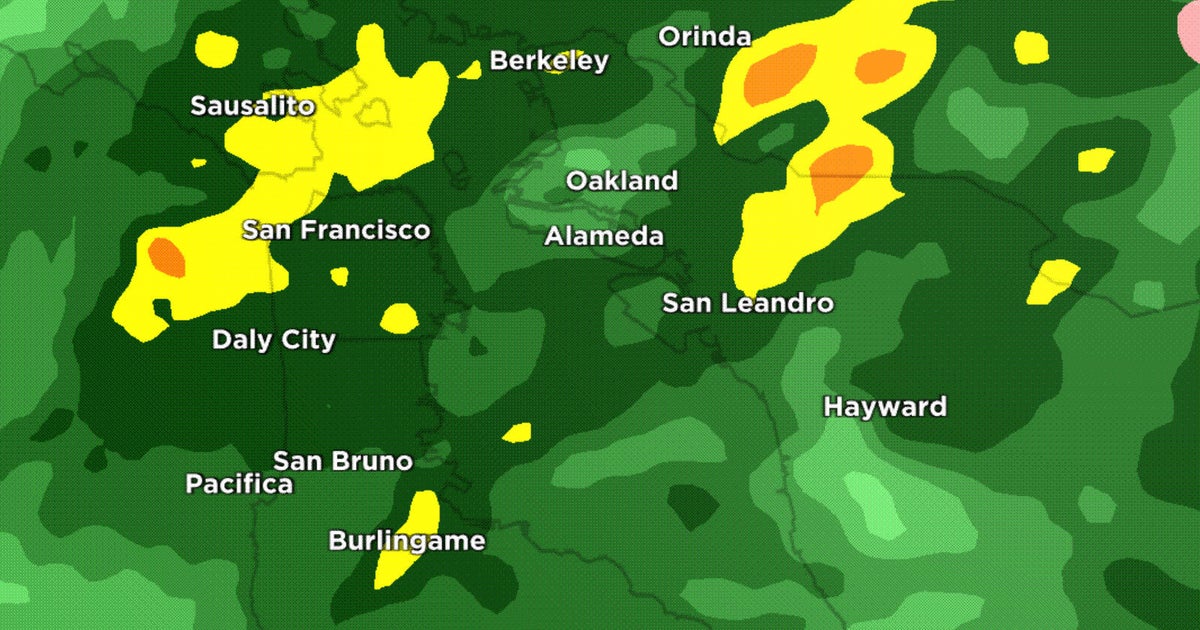

SAN FRANCISCO (AP) — After California's driest three years on record, there have been few sounds as disturbing to water conservationists as the whisk-whisk-whisk of automatic lawn sprinklers kicking on directly behind TV reporters covering some of the state's first heavy downpours in years.

Recent storms eased the drought somewhat, but there's a long way to go. And state officials are worried that the rain will give people an excuse to abandon the already inconsistent conservation efforts adopted to deal with the dry spell.

When Gov. Jerry Brown declared a drought emergency in January, he asked people to cut water use by 20 percent. Instead, many Californians' water use actually went up for a while. Dozens of communities called for mandatory water cuts but lacked the means to enforce them. So lawn watering, golf course maintenance and curbside car washes went on without interruption.

State officials and weather experts say it's too early to know if the storms are the beginning of the end of the drought. They pledge to keep promoting conservation.

"A deluge like this makes us feel, 'Oh, my God, it must be over,'" said Felicia Marcus, chairwoman of the state Water Resources Control Board, which instituted monthly water-use reporting this year to bring home to Californians how much water they were using.

But "we are in a really deep hole ... and we have to act like we are in the drought of our lives." She said officials will "keep working on it even after the drought because there's going to be another one around the bend."

The water board found last month that some well-off Southern California communities were still using more than 500 gallons per person a day — 10 times the amount used by some poorer cities. Marcus and others pledged to step up education efforts.

Climatologist Bill Patzert, a drought expert at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, rose at 3 a.m. last week to bask in the sound of rain from the first big storm to roll through Southern California in a long time. By dawn, he was glowering at television reports showing water-wasting automatic sprinklers whirring in the rain behind at the scene of mudslides and floods.

"Tell them to turn off their damn sprinklers for a week. Tell them I said so," Patzert said. "We're still in a drought."

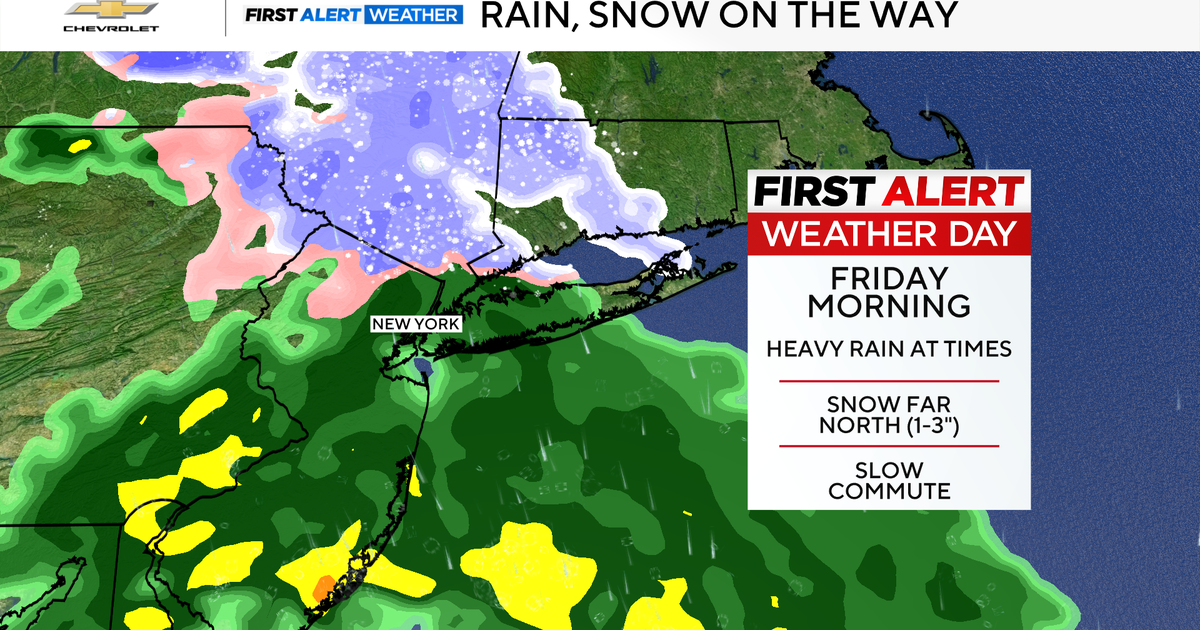

The biggest storm so far this season brought up to 5 inches of rain last Thursday to Southern California, 8 inches in Northern California and 6 feet of snow in the higher Sierras. Sierra snowpack surged, from just 24 percent of average at the start of December to 48 percent of normal on Tuesday, according to the Department of Water Resources.

The snow in the Sierras is all-important, providing the water supply for more than half of California, said Roger Bales, an expert in hydrology at the University of California-Merced.

He is one of many experts trying to spread the message that one or two rains don't end a drought. The key part of the rainy season — January, February and March — still lies ahead, Bales said.

"It's too early in the season to predict we're going to have a wet, average, or dry year. Anything could happen," he said.

This past summer, an estimated $2.2 billion in annual economic losses from lack of rain helped persuade state lawmakers to begin ending unregulated pumping of vital underground aquifers. California was one of the last states in the county that still allowed it. In the fall, voters approved $7.5 billion for water conservation and storage.

But individuals did not show as much commitment. Residents managed peak cuts of 11.6 percent in water use over the summer, but backslid to 6.7 percent in the fall.

California would need 11 trillion gallons of water to replenish its natural water stores, according to a projection this week from scientists using satellite data to analyze snowpack and groundwater.

"It takes years to get into a drought of this severity, and it will likely take many more big storms, and years, to crawl out of it," Jay Famiglietti, another researcher at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said in a statement.

Even so, Fresno County farmer Paul Betancourt was feeling pretty good as he drove this week to his recently planted winter wheat fields. With just 3.3 inches of rain falling on his crop last year, Betancourt was forced to spend $40,000 expanding wells for his 756 acres. Using groundwater to water his fields left white rings of salt in the soil.

With 2.7 inches falling already this winter, that salt is starting to wash away.

"Big improvement on last year," Betancourt said. "Driving, it just looks much fresher. We had to order rain suits."

(Copyright 2014 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.)