New legislation could force schools to stop underreporting cyberattacks

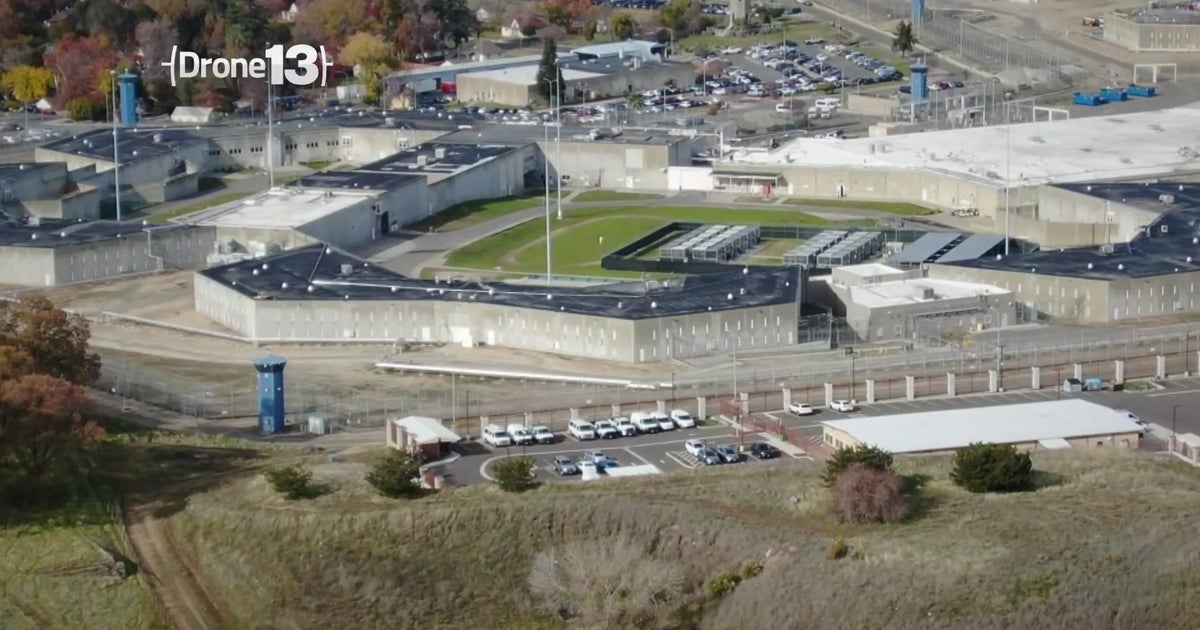

ROCKLIN - Repeated cyber-breaches at schools are not uncommon. But as we've previously reported, schools and districts often hide them from parents. New legislation could change that.

Most kids understand the risk of a cyberattack.

"They can use it all the dark web," said Michael.

It appears, though, that many school districts and lawmakers may not.

From Toledo to Texas, there are reports of data from breaches available on the dark web where kids' information sells for a premium. In Toledo, there were accounts being opened in kids' names.

Last year, we reviewed more than 100 cybersecurity incidents at California schools, but when we asked local school districts about their policies for tracking and reporting cybersecurity breaches, only one out of 50 confirmed it actually had a policy.

"There's a lot of evidence starting to emerge that school districts are actively seeking to avoid disclosure," said Doug Levin, director of the non-profit K12 Cybersecurity Information Exchange, which tracks publicly reported cyberattacks.

But Levin says most schools never report them. This year's annual K-12 cybersecurity report, which cited our investigation, reports a decrease in public reporting by schools, often leaving policymakers, and the victims themselves, in the dark.

"The parents, the students, the educators, they can't take the steps they need to take to protect themselves and their own identities," he said.

California historically tops the FBI's internet crime report for total victims and money lost. Although we're among the top states for school cyberattacks, there is (no) requirement (for schools) to report ransomware attacks to either state or federal entities.

And while schools are required to report certain breaches to victims, we found that many don't due to lack of enforcement or loopholes. For instance, one local district that didn't report two recent attacks told us it would only notify families based on advice from its insurer.

"The insurance companies should not be the ones making that determination," said Levin.

Speaking of loopholes, this new bill would have required districts to report even attempted cyberattacks to parents. But Levin notes it's been significantly watered down. It only requires schools to report breaches to the state's cybersecurity agency, and only if they impact more than 500 people -- meaning victimized children and their parents may remain in the dark.

Levin says that many schools have fewer than 500 kids so they may not have to report breaches. And most breaches happen to vendors, not the school itself, so it's not clear how, or if, vendor breaches would even be tracked.