Scientists say dry lightning could happen more often in California

Dry lightning has ignited some of the most destructive and costly wildfires in California history, a new study shows.

Researchers found that over the past few decades, nearly half of the lightning strikes that hit the ground during spring and summer had been dry — there was no rain falling nearby. Dry lightning tends to happen in storms over areas of extreme drought, like the one California has been in for the past several years. The air is so dry that the rain evaporates before it hits the ground.

And the conditions that favor dry lightning are becoming more widespread and more frequent as the climate crisis fuel's the West's megadrought.

Dmitri Kalashnikov, lead author of the paper and a doctoral student at Washington State University, pointed to the wildfires that scorched California in 2020 — particularly the August Complex Fire, the largest wildfire in the state's history — as the motivation for the research.

The August Complex Fire was originally more than three dozen fires that were sparked by dry lightning. Those fires merged to become the largest in state history, burning more than a million acres in seven counties. California firefighters were exhausted that summer, CNN reported at the time, and they were particularly concerned about the potential for more and more fires sparked by dry lightning.

All of the seven largest fires in California history have occurred in the past five years, and four of those were caused by lightning, according to data from Cal Fire.

"With warming and drying and drier vegetation, it doesn't take a whole lot of lightning to start wildfires," Kalashnikov told CNN. "So even if, on the off chance, dry lightning decreases in the future, it just takes one outbreak one day in a year to cause a lot of fire and a lot of damage, if that were to happen."

The study, funded by NASA and published Monday in the journal Environmental Research: Climate, is the first to develop long-term climatology of dry lightning in California, specifically focusing on Central and Northern California, an area where lightning is a significant cause of wildfire.

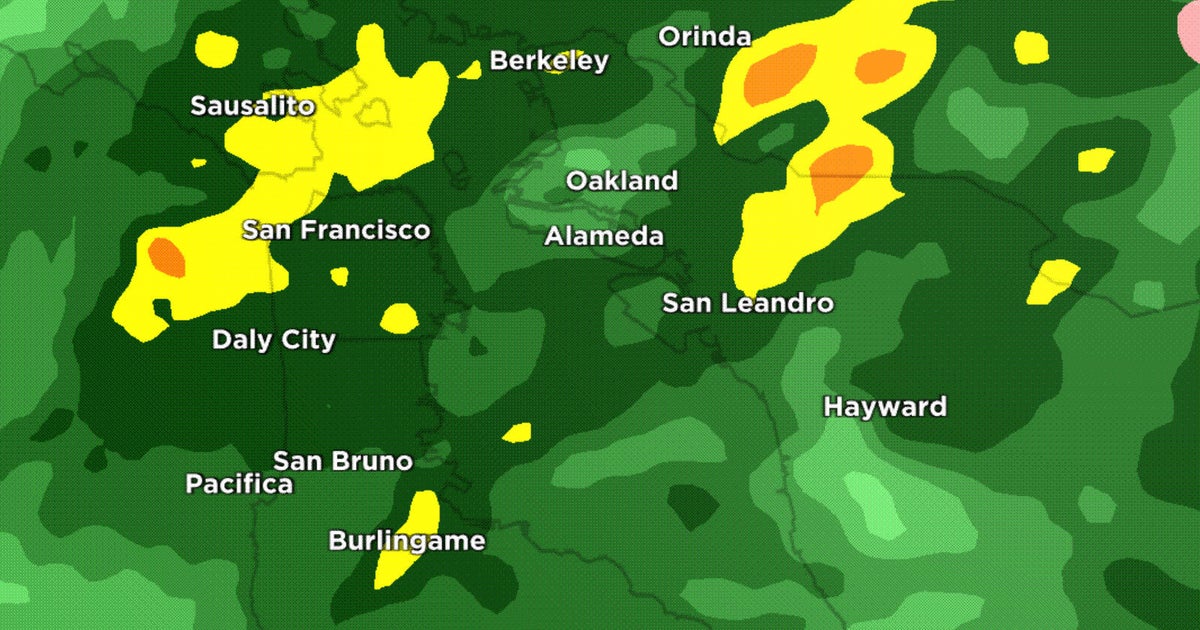

Dry lightning was found to occur most frequently in July and August, the researchers found, though lower elevation regions tended to see activity peak later in September and October, when vegetation is even drier.

Researchers found that around Sacramento, San Francisco, Redwood, Sequoia and Yosemite, lightning sparked nearly 30%, of fires which accounted for nearly 50% of the total burned area.

"That is a lot of fires started by lightning, which are usually more difficult to attack because they tend to be more remote than human caused fires," Chris Vagasky, a meteorologist and lightning applications manager at Vaisala, told CNN.

Vagasky, who is not involved with the study, said the findings provide "excellent background" for weather forecasting and wildland management communities to better determine the conditions that are favorable for dry lightning to occur in advance.

"This really highlights the importance of understanding when dry lightning can be expected so that crews can be at the ready in the event of fire starting," he said. "So it's good to see that there is now a study for this region of the US that shows not just the time of year, but the type of meteorological conditions that appear favorable for dry lightning."

The research is just the first step, Vagasky said. "When thunderstorms do develop, first responders need to be aware that dry lightning conditions may be possible, but they will also have to be able to quickly respond to areas that are impacted," he added.

Kalashnikov said there are still uncertainties when it comes to lightning research, whether dry lightning will occur more often as the climate changes. But one thing is certain, he said, as the Western drought persists, conditions are much more favorable for dry lightning to take shape. In just the last year alone, dry lightning has sparked deadly and destructive wildfires such as the Bootleg Fire in Oregon that burned more than 400,000 acres.

"We know it's getting hotter and drier — California is becoming hotter and drier," Kalashnikov said. "So we can say that no matter what the trend in lightning is doing, when lightning happens with a hotter, drier atmosphere and vegetation, it's just going to lead to more of a risk of these kinds of wildfire outbreaks like we saw in 2020."