Wine vineyards are ripping out their fields because there isn't enough demand

Usually, the grapes growing in Garret Schaefer's California vineyard are destined to become fine wines — but not this year. Fifty acres or 400 tons of the grapes have been left to rot on the vineyard due to too much supply and not enough demand.

"They're turning to raisins. They'll just end up falling off," Schaefer said.

Global wine consumption was down an equivalent of 3.5 billion bottles in 2023, according to the International Organization of Wine and Vine.

Schaefer blames the decline on inflation. The price of a liter of wine rose more than 13% in just the last five years, according to the Federal Reserve Board of St. Louis. Sales also took a hit this year after the World Health Organization declared no level of alcohol consumption is safe for people's health. And there's a generation of young people who just aren't drinking alcohol as much as baby boomers.

Brianda Gonzalez is one young consumer shying away from traditional wine, saying she realized that drinking it regularly wasn't good for her.

"My dad's a bartender by trade, but a few years ago, he got sick. So that meant alcohol had to be cut out. So I went down this whole rabbit hole of non-alcoholic drinks and became fascinated by the category," Gonzalez said.

Her preference now is non-alcoholic beverages, which sells at her shops in California. Sarah Chacon and her sister Helen are among their steady stream of customers.

"I do not drink wine. I've actually never been a big fan of wine, but I do like an alternative," Helen Chacon said.

Sarah Chacon said she's been cutting back for "health reasons."

In California, where 80% of the country's wine grapes are grown, the effects have been dramatic.

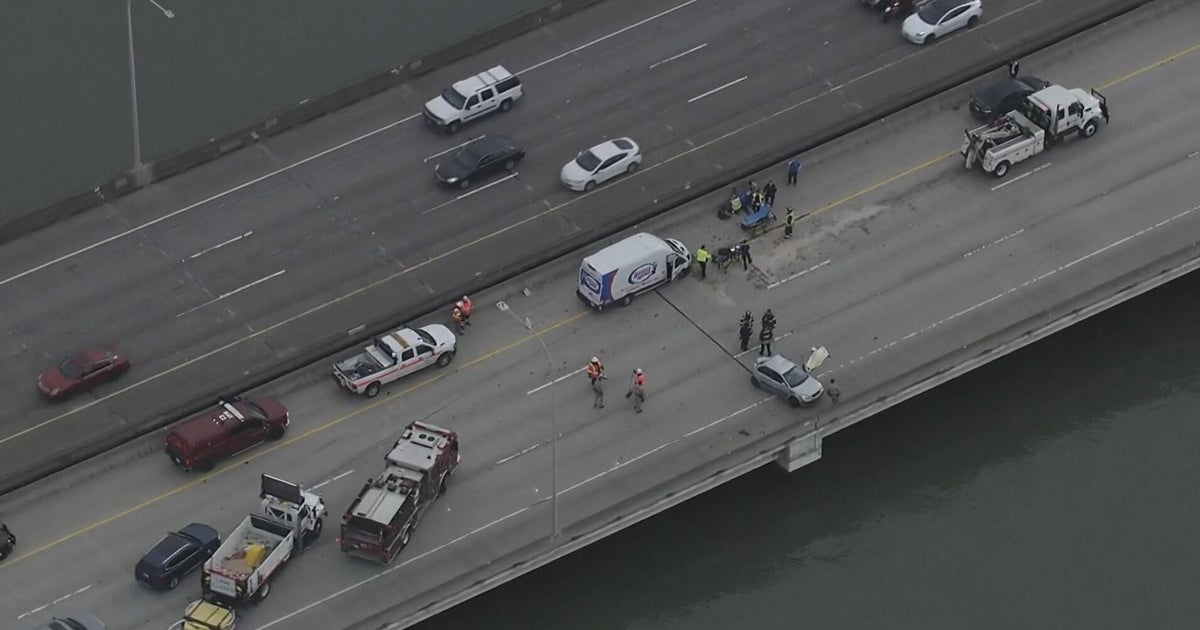

For more than 50 years, Don Worley built his business around weeding out diseased vines. These days, growers hire him to clear out their fields. Heavy machines rip out row upon row of vines from the ground. One tractor can clear out about 30 acres in a day, Worley said.

"What did it cost this man? $20,000 an acre, perhaps? Now he's throwing it away," Worley said.

All together, Schaefer says he's ripped out 60 acres — one third of all the vineyards his family has farmed since 1894. Gone, too, are the people who worked the land.

"We used to have six to eight full time employees through the year. We're down to two of us," Schaefer said.

The problem may only get worse. Experts recommend ripping out 50,000 more acres, or 8% of all the vineyards left in California. It's a new reality here — far more painful than simple sour grapes.