Calif. Trying New Approach For Parole Violators

SACRAMENTO (AP) -- Ex-convicts who violate their parole in California typically are sent back to prison for four months with little if any rehabilitation or education before they are released again.

The result is a cycle of release-and-incarceration that leads to seven in 10 parolees being sent back to prison and drains ever more money from the state's deficit-plagued general fund. In an attempt to break that cycle and save money, state corrections officials have begun trying an approach that could serve as a national model for handling parole violators.

Parolees in the trial program are sent to county jail for brief periods every time they break the rules or test positive for drug use, instead of being sent back to prison. The goal of the short but immediate incarceration is to change their behavior, even if it requires multiple jail stints.

"Usually after two to three times, the light bulb goes (on)," said Denise Allen, a researcher with the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation.

Preliminary results have been "remarkable" for deterring drug use by the 35 Sacramento-area parolees who have participated in the program since it began in November, said Angela Hawken, an associate professor of public policy at Pepperdine University, who is evaluating California's program.

The immediacy and certainty of being sent to jail for every parole violation has seemed to work where the delayed threat of a new and even longer prison sentence had failed in the past, said Hawken, who also has studied similar programs in Hawaii and Washington state.

California plans to expand the program as it attempts to reduce corrections spending and fix overcrowded conditions in its 33 adult prisons. The effort takes on new urgency after the U.S. Supreme Court earlier this year upheld a lower court order requiring the state to reduce its prison population by about 33,000 inmates over two years to improve conditions.

Under the state's trial program, recently released criminals are required to show up at a parole office for drug testing as often as six times a month for 13 months. Those who test positive for drug use, skip appointments with their parole officers, fail to attend 12-step or anger-management programs, or have other technical violations are handcuffed immediately and sent to jail for up to six business days.

Those sent to jail more than three times within a short period are generally considered for a drug treatment programs or returned to state prison. Those who commit new crimes or more serious violations, such as fleeing, also can be sent back to prison.

Corrections officials did not know whether felons who had served lengthy prison sentences would respond to a two- or three-day stay in county jail. But, Lee Seale, the department's deputy chief of staff, said the immediate disruption to their lives seems to get their attention.

"I've seen offenders burst into tears and plead, `Not now,"' Seale said. "They get very sick and tired of it."

Not everyone thinks the experimental program is the answer. State Assemblyman Jim Nielsen calls it "logically absurd."

Nielsen, a Republican who served nine years as chairman of the California Board of Prison Terms in the 1990s, said it is foolish to expect better results when four-month prison sentences are replaced by short jail terms. That is especially true when neither period of incarceration provides any rehabilitation, he said.

"They talk about flash incarceration; that means going in for just a short period of time," Nielsen said. "Oh, so that's going to work when even longer consequences don't work?"

California is the first to experiment with using such a rapid incarceration program for parolees. Washington state started a similar program in Seattle in January. Pennsylvania also plans a program for parolees.

Hawaii's program is for offenders who were placed on probation rather than given a prison sentence.

About three-quarters of California's nearly 106,000 parolees could qualify for the program, officials say.

Larry Winters credited the program with helping him break a 40-year heroin addiction -- until he recently was arrested again on a drug possession charge.

Winters, of Sacramento, was returned to prison twice after his parole in July 2009. He's been sent to prison 11 times since 1985. He was placed in the experimental program in November, and soon obtained a driver's license, a mobile home and a job.

"The things that don't happen when you have an addiction, start happening," said Winters, 65.

Seale said Winters could be brought back into the program after his release from custody.

Supporters of the program say it is the swiftness and certainty of the punishment that seem to make the difference. Parolees outside the program are tested on average once per month, and a positive drug test may or may not result in revocation of their parole.

That is being replaced with a system in which parolees face a potential penalty every time, without exception.

It's too soon to tell whether the program also is deterring new crimes or parole revocations, but supporters point to the success of a seven-year-old program in Hawaii that sends probation violators to jail for short periods instead of to state prison.

Participants in Hawaii's Project HOPE were 72 percent less likely to use drugs, 55 percent less likely to be arrested for a new crime and 53 percent less likely to have their probation revoked, according to an assessment of the project last year by Pepperdine and the University of California, Los Angeles.

California is trying the same program for parolees, who are generally more hardened criminals. Parolees are trying to rebuild their lives after years in prison, while probationers often keep their jobs and families intact even if they serve time in local jails.

State officials expect to share preliminary results from the program at the American Society of Criminology annual meeting in Washington, D.C., in November. So far, just 2 percent of participants are testing positive for continued drug use.

"Anything under a third is great; 2 percent is remarkable," said Hawken, the Pepperdine University researcher.

Hawaii's program saved more than $4,100 for each offender, researchers found, because as a group they spent one-third as many days in prison for breaking probation rules or committing new crimes.

Hawken said California could save substantially because it is the nation's largest state prison system.

Parole violators who are not participating in the program are returned to prison for an average of nearly four months instead of going to county jail for a few days at a cost to the state of $77 a day.

California's prison costs are the nation's highest at an annual average of $44,688 per inmate, compared to an average of $29,000 among 33 states surveyed by the Pew Center of the States in 2008.

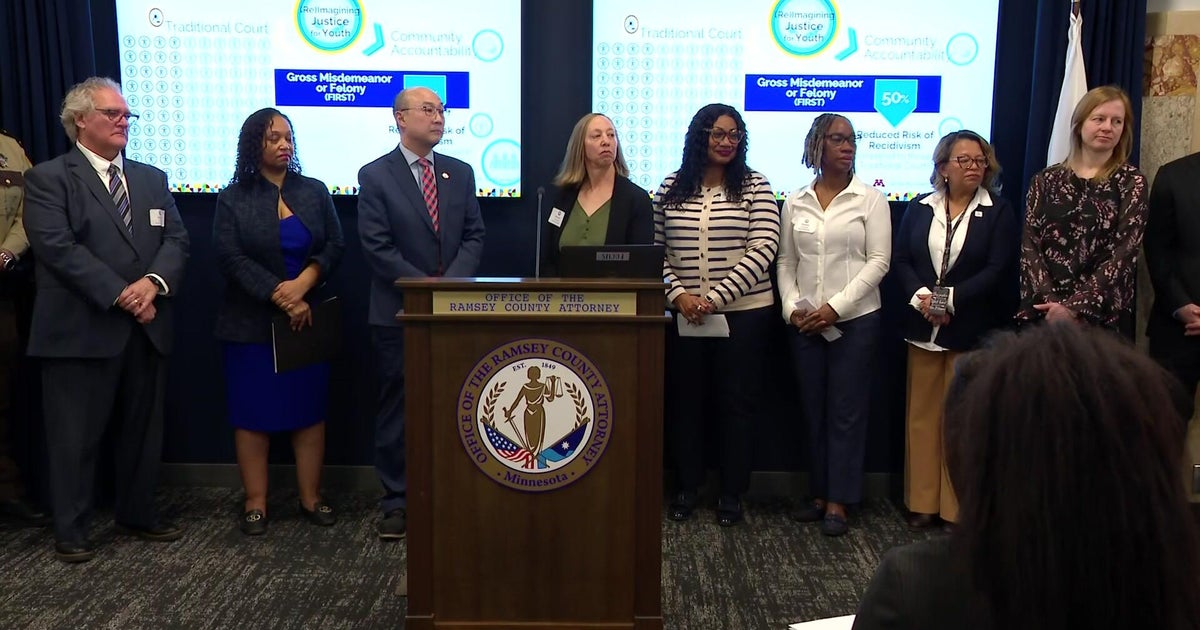

California also has the nation's second-highest recidivism rate, with nearly 70 percent of parolees returning to prison within three years. Only Minnesota has a higher rate, according to an April report by the Pew Center.

Hawaii Circuit Court Judge Steven Alm, a former U.S. attorney, said in an interview that he started the program in cooperation with local police and prosecutors in 2004 out of frustration. He said he often faced a choice between ignoring technical violations or sentencing offenders to prison for terms that were disproportionately harsh.

He modeled the program on the way he had been raised as a child.

"If you misbehave, there was a consequence immediately," he said.

(Copyright 2011 by The Associated Press. All Rights Reserved.)