Armstrong Doping Probe: Evidence Vs. Politics

Lance Amstrong's name surfaces at least once a month along with the words "cycling," "doping" and "grand jury."

His teammates are being questioned. A consultant. A business associate. A former friend.

Records of companies that sponsored him are of prime interest.

And last week, all this snooping moved across the Atlantic to France.

Soon, maybe just weeks from now, federal prosecutors likely will need to make a choice. They either stop chasing Armstrong, or they present a charge that ties one of the world's most famous athletes to drug use.

It's a decision that involves more than simply weighing the evidence.

Armstrong's popularity, his wealth, his ties to powerful figures including former U.S. presidents, his vehement denials, scores of clean drug tests - and, above all, his status as a cancer survivor and advocate for eradicating the disease - make him an incredibly tough target.

But for those who believe Armstrong cheated, all of those obstacles are less important than striking perhaps the biggest blow to date against performance-enhancing drugs.

"If you're going to aim that high you'd better be sure you have a rock-solid case," said a former federal prosecutor, Laurie Levenson of Loyola University Law School. "Jurors will want more than proof beyond a reasonable doubt when you're trying to bring down one of their heroes. They will want proof beyond any doubt."

Armstrong became an important figure in a federal probe of cycling this spring after disgraced 2006 Tour de France winner Floyd Landis came forward with claims that Armstrong and his seven Tour-winning teams, most sponsored by the U.S. Postal Service, ran a complex doping program.

Exactly what he could be charged with remains hazy, primarily because the grand jury hearing evidence in Los Angeles meets in secret.

Still, there are some logical avenues for the U.S. attorney's office and Jeff Novitzky, the Food and Drug Administration agent who played a key role in the BALCO investigation and is helping with this one.

While doping in a French race isn't illegal in America, some things that go with drug use could be. For example, authorities could try to prove Armstrong and his team committed fraud or tax evasion by using money to fund a doping regimen that was classified for another purpose. Or, as with the cases against high-profile athletes (Marion Jones, Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens), they could try to show Armstrong lied or obstructed justice by denying he doped.

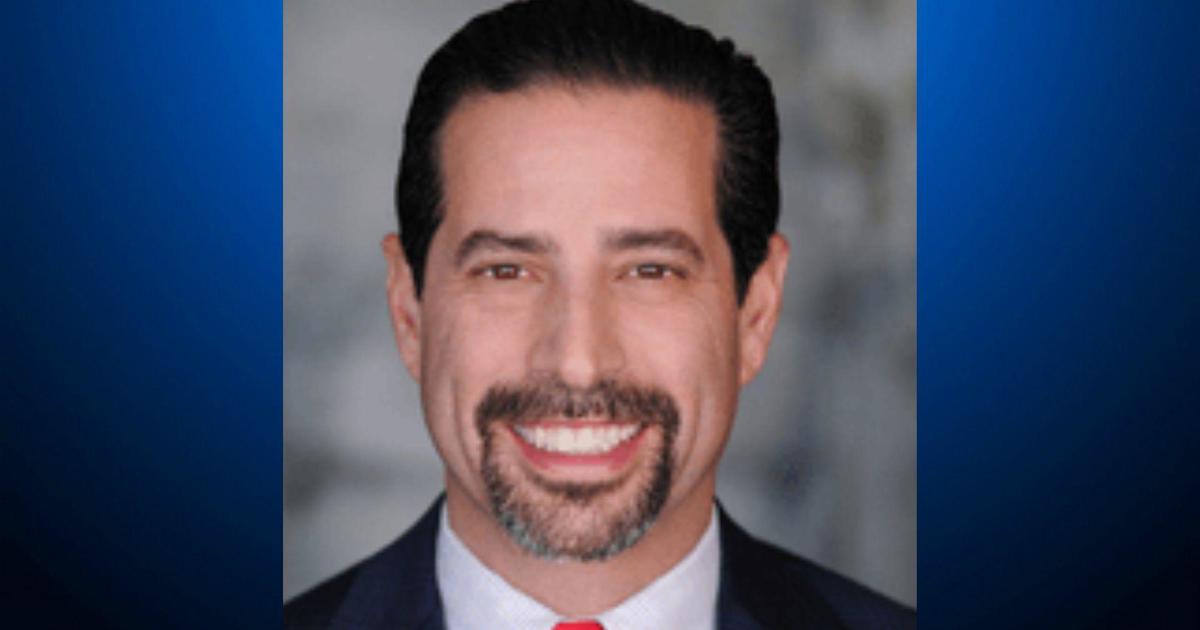

Mathew Rosengart, a former federal prosecutor who is not involved in the case, said attorneys may be able circumvent the five-year statute of limitations on some alleged crimes if they charge Armstrong or others with conspiracy.

"The federal conspiracy statute is often referred to as a federal prosecutors' 'darling,' because it is so broad and is generally more understandable and less difficult to prove than an underlying technical offense," Rosengart said.

Whatever the specifics of the evidence, federal lawyers already are being questioned about the wisdom of going after Armstrong. A person briefed on the case, who spoke on condition of anonymity because the discussions were private, said there's a debate within the Department of Justice and other federal offices about the investigation, and whom it should target.

Armstrong remains hugely popular, but his positive ratings have declined in the wake Landis' allegations in May.

"With the prosecution of Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens and this extension into international cycling, the question will be, has the government gone too far in targeting professional athletes?" Armstrong's attorney, Bryan Daly, said in a recent interview with The Associated Press.

Daly isn't the only one asking the question.

There's a "Support for Lance" website that urges followers to be there for the "international hero" at a time when he needs it most.

There are fans, such as those who expressed disapproval of the ongoing probe on the AP's Facebook page when it posted a story that U.S. investigators were working with French anti-doping authorities to collect evidence. Many of their comments were complaints about the government wasting its money when the economy was bad and unemployment high.

There was a letter written last summer to FDA commissioner Margaret Hamburg from Allen Vaught, a member of the Texas state House of Representatives and Armstrong supporter, who said "during these challenging times, the FDA should be using taxpayer resources to address ... other pressing life and death matters, and not a retired athlete."

And Armstrong has even more-impressive friends in government. Earlier this month, he tweeted a thank you to George H.W. and Barbara Bush for their support. He has worked with the foundation run by former President Bill Clinton.

Mostly, though, there are the supporters of Armstrong's charitable foundation, Livestrong, which attracts nearly 7 million visitors a month to its website, according to Fast Company magazine. Armstrong has sold an estimated 70 million yellow Livestrong bracelets at $1 each.

Among his fans is Gregory De Respino, whose wife, Gail, died of cancer in 2009. De Respino has tattoos spread across his body that tell his life story, one of which is the word "Livestrong," inked across his wrist as a permanent replacement for the yellow bracelet he once wore.

"He's a greater benefit to people untarnished than tarnished, I know that," De Respino said of Armstrong. "You have to look at the facts as they're presented. He's the one who beat cancer. He's the one who's been resilient. He's done nothing but good and he's the most-tested athlete on the planet. He's passed every test."

De Respino said he's written a number of checks to support Armstrong's cause and has an idea for a play that uses cycling as a metaphor for life. His dream is to produce the play and donate the earnings to Livestrong because "they're helping people I don't have access to."

De Respino's story is one of thousands that, collectively, portray the strength of Armstrong and his message - and the potential fan base the federal government could antagonize by going after the cyclist.

"When you have someone with star power, a jury will be inclined to give them a true presumption of innocence," said Mark Geragos, a top defense attorney in Los Angeles.

But if there's a "good" time for the government to target Armstrong, psychologist Stan Teitelbaum argues this could be it.

"There's been a lot of negative publicity," said Teitelbaum, who wrote the book "Sports Heroes, Fallen Idols." "The whole Landis thing, well, Landis is a big liar but he cast a large shadow over Armstrong. Now you look at it and say, 'Even if you're a liar, it doesn't mean everything you say is a lie.' Some people have started to believe there could be a degree of truth there."

Among those seeking the truth are the people those in the anti-doping world call the "true believers" - the ones who want performance-enhancement drugs snuffed out of the sport and are willing to pay the price. They worry about the possible long-term health consequences of PEDs, to say nothing of the message that cheating sends to children.

They say the oft-criticized cost of an investigation such as this - which could reach into seven figures - is nothing when set against, say, the salary of a single pro athlete in a high-profile sport.

In their minds, Armstrong should get no slack for being famous or an advocate, and they make no apology for staying on the case even if he hasn't won the Tour since 2005. David Howman, the director general of the World Anti-Doping Agency, said anti-doping authorities often get criticized for going after the "small fry" in sports to gain easy convictions and give off the perception of success.

"People see that and say, 'What about going after the big fry?"' Howman said. "You just have to believe that whatever comes from this inquiry will be thorough and the evidence will be used properly. I have no issue with the integrity of it."

But outside of Howman, who said last month the Armstrong investigation could produce information "equally as significant as BALCO," there are very few on the anti-doping or prosecutorial side who will speak publicly about the case.

Graeme Steel, the president of the Association of National Anti-Doping Organizations, is one of those who will. He bemoans the baggage that looking into Armstrong's career carries for prosecutors.

"One of the problems with politicizing it is, it muddies the water," Steel said. "It doesn't become a straight clinical investigation. It becomes a media circus and that doesn't help.

"If there's strong evidence, you keep after it. If there's not, you don't," he said. "If that evidence takes us down to a prima facie case that says while he may have done good things, he's the biggest sporting fraud of the century, then you'd want to find out. If there's no prima facie case and the evidence is, this is going nowhere, then that's fine, too. You just have to answer the questions."

Armstrong believes he's answered questions too many times to count. For now, though, his lawyers are toning down the hyperbole and taking a wait-and-see approach.

"Celebrities should not be given lenient treatment by law enforcement," Daly said. "On the other hand, the opposite holds true - a celebrity should not be hunted and prosecuted simply because he is a celebrity."

© MMX, The Associated Press. All Rights Reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.