Artists sue AI company for billions, alleging "parasite" app used their work for free

As AI-generated images proliferate across the internet, two lawsuits are seeking to rein in the potent technology as well as ensure the artists who unwittingly helped train the tools are financially compensated for their work.

The litigation, which targets the company behind the Stable Diffusion engine, represents the first legal actions of its kind and could redefine the rights and protections of computer-generated art as the technology make rapid advancements.

A suit filed by Getty Images this week in the U.K. claims the company, Stability AI, illegally scraped the image service's content. And a class-action lawsuit, filed in California federal court on behalf of three artists last week, alleges that the software's use of their work broke copyright and other laws and threatens to put the artists out of a job.

The tool "is a parasite that, if allowed to proliferate, will cause irreparable harm to artists, now and in the future," Matthew Butterick, one of the artists' lawyers, alleged in a statement outlining the case.

AI's "ability to flood the market with an essentially unlimited number of [similar] images will inflict permanent damage on the market for art and artists," he claimed.

Copying or creating?

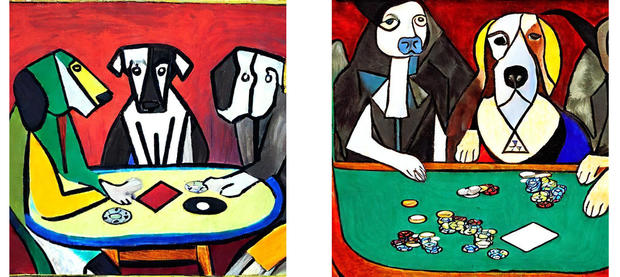

Stable Diffusion, released this year and now used by 10 million people a day, is just one of several tools that can almost instantaneously create images based on a string of text entered by the user. Similar technology is behind the apps DreamUp and DALL-E 2, both released last year.

To operate, these tools are first "trained" by being fed vast amounts of data. For instance, a system could absorb a billion images of dogs and, by parsing the differences and similarities between these images, come up with a definition for "dog" and eventually learn to reproduce a "dog."

Stability AI, the first open-source image generator, trained its systems on images from across the internet. An independent analysis of the origin of those images shows at least 15,000 came from gettyimages.com; 9,800 from vanityfair.com; 35,000 from deviantart.net; and 25,000 from pastemagazine.com.

The court's view of whether or not that violates copyright laws will likely depend on how it understands AI to function.

"One version of the story is, the AI system scoops up all these images and the system then 'learns' what these images look like so that it can make its own images," said Jane Ginsburg, a professor of literary and artistic property law at Columbia University.

"Another version of the facts is the system is not only copying, it's also pasting portions of the copied material, creating collages of the stored images, and that's the claim that was filed in California — that these are actually big collage machines."

The artists' suit argues that, because the AI system only ingests images from others, nothing it creates can be original.

"Every output image from the system is derived exclusively from…copies of copyrighted images. For these reasons, every hybrid image is necessarily a derivative work," the complaint alleges.

"Stability did not seek consent from either the creators of the Training Images or the websites that hosted them from which they were scraped," the suit further claims. "Stability did not attempt to negotiate licenses for any of the Training Images. Stability simply took them."

Since launching its publicly available apps, Stability A, recently valued at $1 billion, "is not sharing any of the revenue with the artists who created the Training Images nor any other owners of the Works," the suit alleges.

How much revenue could that be, exactly? At the low end, artists could be owed $5 billion, their lawyers suggest.

A fair shake

The artists' goal isn't to stymie the development of AI but rather ensure creators get a fair financial shake, according to Joseph Saveri, one of the attorneys representing the three artists.

"Visual artists, especially professionals, aren't naive about AI. Yes, it is going to become part of the social fabric, and yes, in certain cases it will displace jobs," he said in an email. "What these artists object to, and what this case is about, is Stable Diffusion settling on a business strategy of massive copyright infringement from the outset."

Getty Images has a similar argument, alleging that the software "unlawfully copied and processed millions of images protected by copyright," ignoring licensing options Getty offers for AI systems to use.

Stability AI is pushing back against these claims. "The allegations represent a misunderstanding about how our technology works and the law," a spokesperson for the company said. The spokesperson added that Stability had not yet received formal notice of Getty's legal action.

"Learning like people"

The CEO of Midjourney, another AI image creator and a defendant in the California suit, recently described the tool as similar to a human artist.

"Can a person look at somebody else's picture and learn from it and make a similar picture?" David Holz told the Associated Press in December, before the suit was filed.

"Obviously, it's allowed for people and if it wasn't, then it would destroy the whole professional art industry, probably the nonprofessional industry too. To the extent that AIs are learning like people, it's sort of the same thing and if the images come out differently, then it seems like it's fine," he said.

Making a living

AI is already being used to illustrate articles and magazine covers and even to create entire books.

"It'll create brand-new industries, and it will make media even more exciting and entertaining," Stability AI CEO Emad Mostaque recently told CBS Sunday Morning. "I think that creates loads of new jobs."

But as champions of the technology tout its potential to expand human creativity, the creators currently doing the work are worried tech will put them out of a job.

"Why would someone hire someone when they can just get something that's 'good enough'?" Karla Ortiz, a concept artist, asked CBS Sunday Morning. Ortiz, one of the three artists suing Stability AI, spoke with CBS News before the suit was filed.

Cartoonist Sarah Andersen, another of the plaintiffs, has written about seeing her comics appropriated and parodied by online trolls and now crudely reproduced by AI search engines. Illustrator Molly Crabapple has called AI "another upward transfer of wealth, from working artists to Silicon Valley billionaires."

Similarities to music piracy

The emergency of image-scraping AI is drawing comparisons to the late 1990s, when the music industry sued file-sharing service Napster, which people were using to copy and share music. Napster lost, went bankrupt and was later replaced by superior streaming-based music services such as Spotify, which license music from creators.

The following decade, the Authors Guild sued Google over the company's Google Books project, which had scanned and stored copies of 15 million books, half of which were under copyright. By the time the case was decided in 2015, the court ruled that Google's presentation of the text as snippets, as well as the security precautions it took, meant the project wasn't, in fact, breaching copyright law.

"When the case was filed, not a lot of people would have thought that putting millions of books in the database of a for-profit company would be fair use. The law evolved and by the time the case was decided, it was fair use," Columbia's Ginsburg said.

Artists are hoping the case is decided more like Napster.

"The idea of streaming music was valid, but doing it legally ultimately meant bringing the songwriters and musicians to the bargaining table to make a deal," Saveri said. "I think we'll see the same pattern in AI — these companies will realize that they can offer better products by making fair deals with creators for training data."