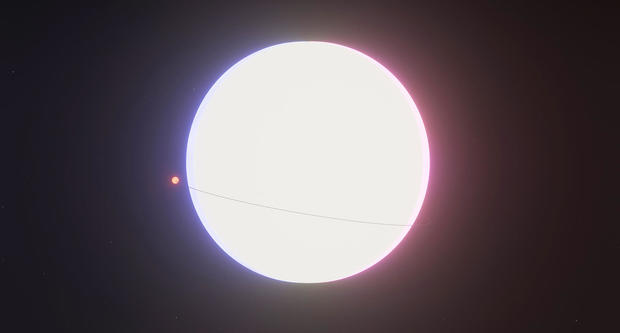

A year only lasts 17.5 hours on the "hell planet"

The exoplanet 55 Cancri e goes by several names, but the rocky world located 40 light-years from Earth is most known for its reputation as a "hell planet."

This super-Earth, so named because it's a rocky planet eight times as massive and twice as wide as Earth, is so scorching hot that it has a molten lava ocean for a surface that reaches 3,600 degrees Fahrenheit (1,982 degrees Celsius).

The exoplanet's interior might also be full of diamonds.

The planet is hot enough that it has been compared to the Star Wars lava world of Mustafar, site of the battle between Anakin Skywalker and Obi-Wan Kenobi in "Revenge of the Sith," and where Darth Vader later establishes his castle, Fortress Vader.

The planet, formally named Janssen but also referred to as 55 Cancri e or 55 Cnc e, orbits its host star Copernicus so closely that the sizzling world completes one orbit in less than one Earth day. One year for this planet lasts about 17.5 hours on Earth.

The incredibly tight orbit is why Janssen has such intensely hot temperatures — so close that astronomers doubted a planet could exist while practically hugging a host star.

Astronomers wondered if the planet had always been so close to its star.

A team of researchers used a new tool known as EXPRES, or the EXtreme PREcision Spectrometer, to determine the precise nature of the planet's orbit. The findings can help astronomers gain new insight into planet formation and how these celestial bodies evolve an orbit.

Evolving orbit

The instrument was developed at Yale University by a team led by astronomer Debra Fischer and installed on the Lowell Discovery Telescope at Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona. The spectrometer was able to measure tiny shifts in starlight from Copernicus as Janssen moved between our planet and the star — like when the moon blocks the sun during a solar eclipse.

The researchers determined that Janssen orbits along the star's equator. But the hell planet is not the only planet orbiting Copernicus. Four other planets on different orbital paths populate the star system.

The astronomers believe Janssen's oddball orbit suggests the planet initially began in a cooler and more distant orbit before drifting closer to Copernicus. Then, the gravitational pull from the star's equator changed Janssen's orbit.

The journal Nature Astronomy published a study detailing the findings on Thursday.

"Astronomers expect that this planet formed much farther away and then spiraled into its current orbit," said Fischer, senior study author and Eugene Higgins Professor of Astronomy at Yale, in a statement. "That journey could have kicked the planet out of the equatorial plane of the star, but this result shows the planet held on tight."

Red-hot exoplanet

Despite the fact that Janssen hasn't always been as close to its star, the astronomers concluded the exoplanet was always scorching hot.

The planet "was likely so hot that nothing we're aware of would be able to survive on the surface," said lead study author Lily Zhao, a research fellow at the Flatiron Institute's Center for Computational Astrophysics in New York, in a statement.

Once Janssen moved in closer to Copernicus, the hell planet became even hotter.

Our solar system is flat like a pancake, where all of the planets orbit the sun on a flat plane because they all formed from the same disk of gas and dust that once swirled around our sun.

As astronomers have studied other planetary systems, they have discovered that many of them don't host planets orbiting on one flat plane, which begs the question of just how unique our solar system is in the universe.

This kind of data could provide more information about how common Earth-like planets and environments may exist in the universe.

"We're hoping to find planetary systems similar to ours, and to better understand the systems that we do know about," Zhao said.

The primary goal of the EXPRES instrument is to spot Earth-like planets.

"Our precision with EXPRES today is more than 1,000 times better than what we had 25 years ago when I started working as a planet hunter," Fischer said. "Improving measurement precision was the primary goal of my career because it allows us to detect smaller planets as we search for Earth analogs."