Former KDKA-TV personality Jon Burnett hopes donating his brain to science will help researchers understand CTE

PITTSBURGH (KDKA) -- Pittsburghers know Jon Burnett from his 36 years on the air at KDKA-TV forecasting the weather, performing crazy stunts on Evening Magazine, Pittsburgh 2Day and Pittsburgh Today Live, and mostly as the fun-loving guy who was the same on TV as off.

Jon retired five years ago, but in the last couple years, he's faced major health challenges and recently got a diagnosis of suspected CTE, likely caused by repeated blows to the head. CTE stands for chronic traumatic encephalopathy and can only officially be diagnosed with an autopsy of the brain upon death, so we rarely get to talk with someone who has what's presumed to be CTE.

KDKA-TV's Kristine Sorensen, who co-hosted PTL with Jon for 11 years, sat down with Jon and his wife Debbie and his grown children, Samantha and Eric, who wanted to share their journey. Jon is already part of research happening right here in Pittsburgh to better understand the disease, and they hope that by telling their story about what they are experiencing, more people will participate in the research.

Over the last couple years, Jon's physical challenges have worsened. His walk has become more of a shuffle, his voice is somewhat hoarse, his expressions are diminished and his short-term memory is a struggle.

He told Kristine, "I miss being able to start a conversation like ours and see it through to the end and feel like I've accomplished something."

It's a big shift from the strong guy who loved to lift people up, leap toward any challenge and have the strength to do it, even into his 60s.

READ MORE: Beloved former KDKA-TV personality Jon Burnett has suspected CTE

Debbie, Samantha and Eric say he still loves playing with his grandkids but it's different now.

"He was, I would almost say hyper-physical -- would jump over stuff, and it's like he was in peak physical shape. And so now, the changes seem quite dramatic," Samantha said.

After tests and scans ruled out other causes for Jon's memory and physical challenges, UPMC Cognitive Neurologist Dr. Joseph Malone concluded Jon has suspected CTE.

Jon played contact football for ten years from childhood to college, including at the University of Tennessee. He estimates he hit his head 30 to 40 times a game, with two major concussions.

"That history, coupled with his symptoms, and in addition to the newer diagnostic criteria for this thing called traumatic encephalopathy syndrome, led me to make that diagnosis for him," Dr. Malone said.

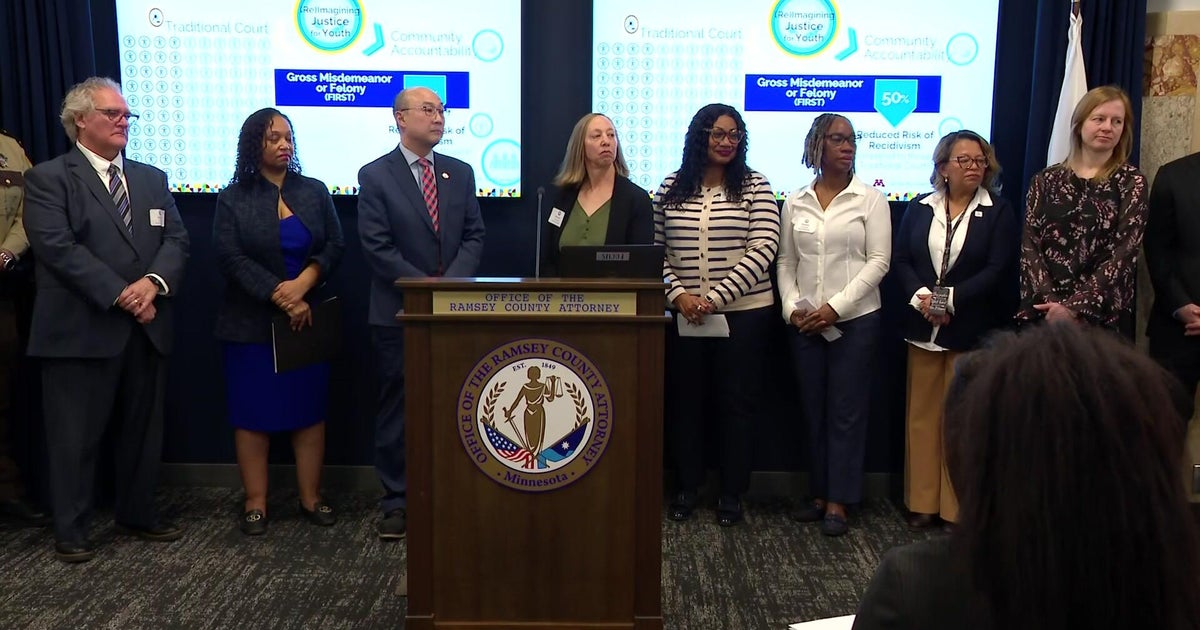

Jon is participating in a study at the National Sports Brain Bank at the University of Pittsburgh, which was created just nine months ago with support from big names like former Steelers Jerome Bettis and Merril Hoge.

The director of the Brain Bank, neuropathologist Julia Kofler, is studying athletes while they're alive and then analyzing their brains after death. She hopes the Brain Bank's findings will help people playing contact sports.

"If you have an understanding of what makes an individual higher risk than another, I think then people can make a more informed decision if that's a risk they are willing to take on," Kofler.

In 2005, a pathologist in Pittsburgh was the first to put CTE in the national spotlight after seeing it in the brain of Pittsburgh Steeler Mike Webster following his death. Since then, research has shown that repetitive head injuries and concussions can cause damage in the brain that can lead to CTE, but still very little is understood about why some develop CTE and others don't.

"I know people who are in their 80s who have played football and don't show any signs of cognitive changes, so we want to know or help learn, to understand what protects these people from manifesting symptoms," Kofler said.

A new study from the Boston University CTE Center looked at the brains of younger athletes through college who played contact sports and died before age 30 and found CTE in 40% of them.

"The vast majority of people who are going to have this disease are not going to be professionals, per se, but people who may just have played a lot of sports in high school and college, which that applies to a lot of people," Dr. Malone said.

That's why the National Sports Brain Bank at the University of Pittsburgh wants anyone who played sports or activities with increased concussion risk to participate in their study -- from recreational sports to professional.

This includes traditional contact sports like football, ice hockey, and soccer to others like cheerleading, motocross and horseback riding. Participants have to fill out an annual online questionnaire and agree to donate their brain upon death.

Jon has agreed to that, meaning his legacy of helping people will continue even after he dies, with each brain used in dozens of studies over decades.

Jon said, "If I can help anybody on this road, who is on this road or will be on this road in the years ahead, I feel better about being able to do that."

By donating his brain, Jon's family will also learn whether he did, in fact, have CTE. But for now, they're taking the cards that were dealt to them and making the most of every moment together in this game of life.

"You just have to change your thinking and try to stay hopeful," Debbie said.

"You will always be Superman to us, for sure," Eric added.

Jon told Kristine, "I am who I am because of football, Boy Scouts, my mother and father and good friends like you and Debbie and my kids, and I wouldn't change that. I wish I was a little clearer-headed, but otherwise, my life is good."

The study at the National Sports Brain Bank will be long-term and will evolve in phases where participants may provide blood tests or undergo scans if they're willing.

So far, about 100 people have expressed interest and half have completed the study questionnaire. They're hoping more people sign up. If you're interested in enrolling or learning more, go here.