New Post-Pancreas Surgery Treatment Could Help Avoid Complications

Follow KDKA-TV: Facebook | Twitter

PITTSBURGH (KDKA) - After a fall down a hill and getting whacked in the lower chest with a tree branch, Bruce Reitman's pancreas became chronically inflamed.

"I was in so much pain, couldn't eat, curled up in a ball so often, going to the doctor crying so often because the pain was so bad."

In some cases, the condition can be related to alcohol, genetics or an autoimmune reaction.

Typical treatments include avoiding food by mouth, sometimes resorting to food by vein and medicine to control the main symptom of pain.

"It hurt a lot and I didn't eat a lot. That's why I lost about 60 pounds," says Bruce. "They had to keep increasing the pain medicine."

More severe cases may require a tube to keep the duct from the pancreas to the intestines open.

But the ultimate surgical procedure is what Bruce had - removing the pancreas, but preserving the insulin-producing cells.

"It's a big surgery and you're losing the pancreas," says UPMC transplant surgeon Dr. Abhinav Humar.

"He said, you know, you're going to be a diabetic?" Bruce recalls, "And I thought that's no problem after all this. I couldn't wait to get it done."

The problem with completely removing the pancreas is it has many important functions. It secretes enzymes important to digestion, and it makes insulin, a hormone important to process sugar and carbohydrates. The digestive enzymes are easily replaced, but without a pancreas, you would become diabetic.

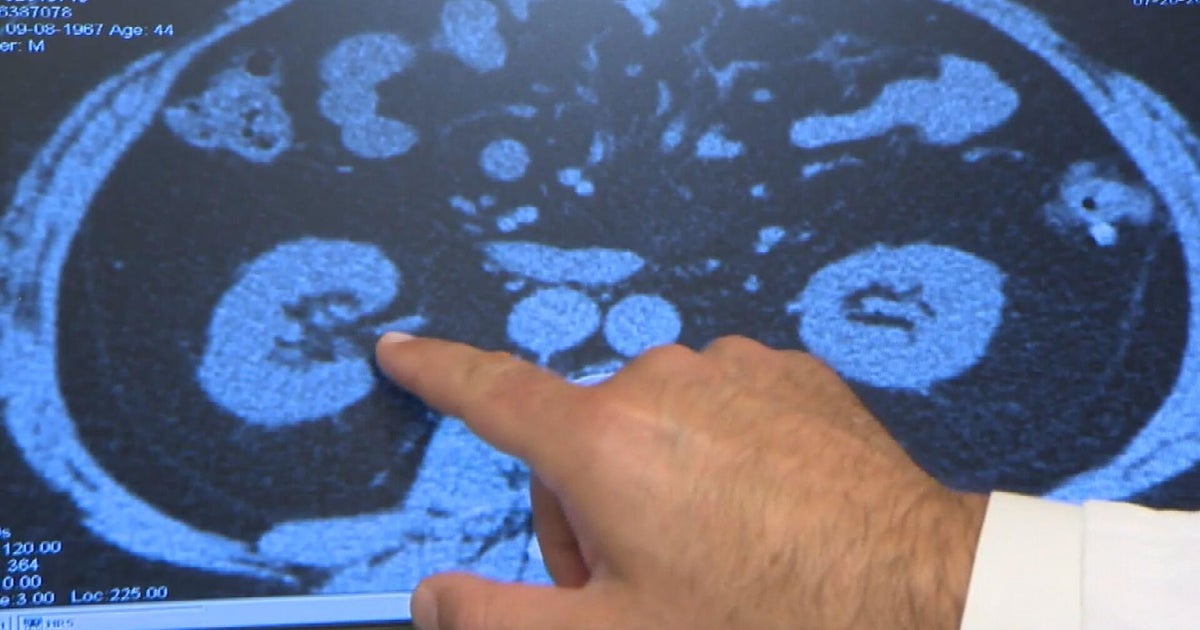

In a day-long operation, the pancreas is taken out and sent to the lab. It is chemically treated and disintegrated.

The islet cells -- the cells that produce insulin -- are extracted and spun down into a small pellet. The pellet of cells is mixed with fluid, and the mixture is injected into the vein leading into the liver.

There, the islet cells make a new home. Patients take insulin until the cells get established.

"They're surprising me how well they're working," says Bruce.

The procedure was developed in 1980, but had significant complications, and fell out of favor. Since 1995, with better techniques and renewed interest, more centers started performing the procedure. At UPMC, they do about 10 cases a year.

"Ninety percent of patients plus get improvement of their pain symptoms," says Dr. Humar. "It's probably the most effective therapy we have for treatment of the pain."

Some people do not get pain relief -- related to trouble getting off the narcotics, or an issue with the pain nerves themselves.

As for the transplanted islet cells -- one-third of the patients will have full function, one third will need some insulin, and another third will make no insulin of their own.

In follow up, doctors monitor blood sugars and a segment of secreted insulin called c-peptide.

Generally, the procedure works better, the more functioning islet cells you have. The longer you have pancreatitis, the more the cells degrade, and the transplant is less likely to work.

"We'd like to try to see those patients earlier in their disease process because I think the likelihood of having a successful outcome is better in those types of situations," says Dr. Humar.

Another challenge -- the price -- $40,000-100,000.

"The process of isolating the islets, the reagents, the time, the process is significantly expensive, so it essentially doubles the cost of the total pancreatectomy," Dr. Humar explains. "Because it's not accepted in the clinical arena, and so it's not covered by some insurance companies."

After a struggle, Bruce feels fortunate his procedure was covered.

"She's happy to see me eat, compared to when I couldn't eat," says Bruce. "I don't really take a lot of insulin. I can eat anything I want now. And do anything I want now."