New Procedure Offering Hope To Afib Patients

Follow KDKA-TV: Facebook | Twitter

PITTSBURGH (KDKA) -- Kathryn Reveille had an abnormal heart rhythm called atrial fibrillation, or Afib.

"I had palpitations. Really, really strong palpitations that were disabling," she said.

She tried medications, and endured eight shocks to the heart. Nothing worked to keep it in a normal rhythm.

Her heart wasn't beating effectively. She couldn't walk without it racing. She had trouble breathing.

"My hospitalizations became more frequent. The stays were longer. One was 23 days," she said

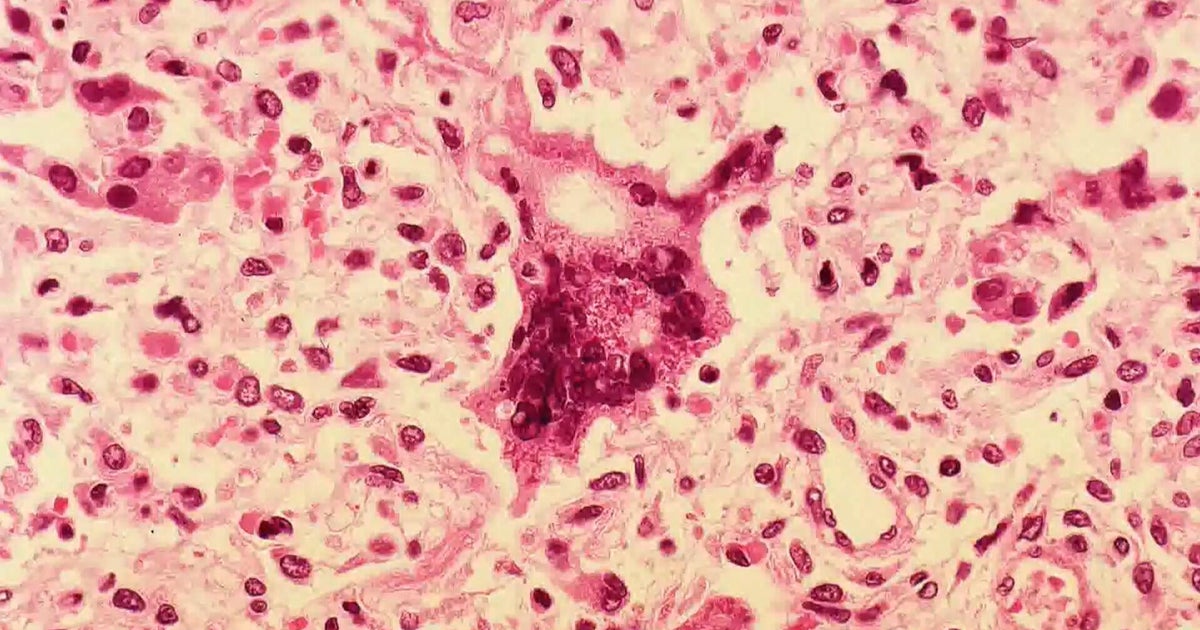

With Afib, instead of just one area, multiple areas in the top chamber tell the heart to beat. With so many signals, the bottom chambers beat irregularly.

"Our goal is to help them feel better. Our goal is to help prevent a stroke," St. Clair Hospital heart surgeon Dr. Andy Kiser said.

Ten years ago, Kiser invented a procedure to control Afib, particularly for people who have been in the rhythm for a long time.

While the patient is under general anesthesia, Dr. Kiser goes in through a small incision in the upper abdomen, and reaches the outside of the heart with tubes and scopes. He burns a pattern into the outside of the heart muscle.

In the same procedure, another heart doctor, called an electrophysiologist, goes through the groin and up to the heart with a catheter, to burn a pattern on the inside of the upper chamber.

"By doing them together, it forms a pattern, that creates a maze-like pattern, without having to stop the heart, without having to open the chest," Dr. Kiser said.

This maze-like pattern corrals the abnormal impulses in the upper part of the heart so they don't travel to the pumping, lower part of the heart.

"About 80 percent of patients who have been in chronic atrial fibrillation who have the procedure, a year later, on our 24-hour monitor, have no atrial fibrillation," Dr. Kiser said.

This is compared to 40 percent at one year with medication.

Of course, there are risks.

"Things like infections, and bleeding, and strokes, and even dying," Dr. Kiser said.

Death occurs in less than a half percent.

The procedure is covered by insurance, and is done all over the world now.

"This is a procedure we invented in my basement in North Carolina, and they're having meetings about it in Rome, Italy," he said.

But it isn't done at every hospital, because it requires a special team of an experienced heart surgeon working with an experienced electrophysiologist.

"If you don't have a partnership, it ain't gonna work," he said.

So far, Dr. Kiser has done three cases like this at St. Clair Hospital since arriving in January.

Kathryn was the first.

"Because it was the first time they were doing it, they were so ready for me. Everything was in place," she said.

"The level of excitement around it, and the enthusiasm, really makes it easy," Dr. Kiser said.

It takes three months for all the inflammation to settle down. Kathryn needed another shock to the heart when a bout of Afib occurred after her January procedure. But her function has greatly improved.

"I don't feel any more palpitations. My heart rate is steady in the 60s. I can breathe. I can walk from room to room. I'm not dependent on my family so much as I was," Kathryn said. "And, I'm looking forward to being able to walk my dogs again."