X-Planes: The world's fastest jets

In the world of aviation, X-Planes hold a special place. They're a glimpse into the future, a look at what's coming in a later generation of aircraft--and, to a degree, spacecraft as well. Over the last seven decades, they've been a proving ground for developments including delta wings, tailless aircraft, and supersonic flight.

Where once the experimental aircraft required the steady hand and quick reflexes of a test pilot in the cockpit, in recent years, they've tended to be unmanned vessels--a central theme in aerospace advances generally. It's those newer, pilotless X-Planes that have been in the headlines of late, first with the X-37B that was launched into orbit last year, and then again with the hypersonic X-51A.

In this slideshow, we'll be taking a look back at X-Planes over the years, starting with this vintage group shot from 1953. In the center is the X-3, and clockwise from the left are an X-1A, a D-558-1, an XF-92A, an X-5, a D-558-2, and an X-4. (A few aircraft, such as the D-558 series and the later M2-F1/2/3 series, never got the "X" designation, though they're included in the family because they served the same goal of flight research.)

X-1 hits Mach 1

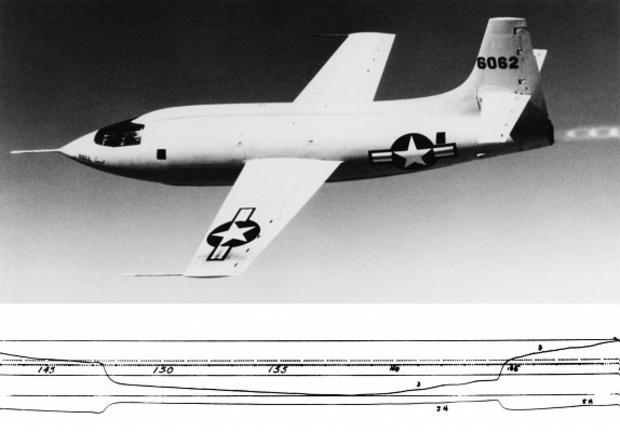

The history of X-Planes begins with the X-1. It wasn't just the first in the lineage--it was the first aircraft ever to break the sound barrier.

That famous flight took place on October 14, 1947, with the legendary Chuck Yeager in the cockpit. The photo here shows the Bell Aircraft X-1-1 in flight, along with a snippet of the paper tape (which tracked the flight data) showing the jump to supersonic speed at Mach 1. (The first glide flight had happened in January 1946.)

NASA points out that the exhaust plume here shows the shock wave pattern. The achievement was classified as top secret; the Air Force would not confirm the supersonic flight until March 1948.

Test pilot John Griffith

Test pilot John Griffith pokes his head out of an X-1 to chat with ground crew members. Although aircraft had not broken the sound barrier until the advent of the initial X-Plane, some munitions apparently had--hence, according to NASA, the fuselage of the X-1 had essentially the same shape as a .50-caliber machine gun bullet, which was known to be stable at supersonic speeds. Under the hood, the X-1 packed an XLR-11 rocket engine, fueled by liquid oxygen and a mixture of alcohol and water.

X-1 instrument panel

X-1 and B-50

From the start, rocket-powered X-Planes typically hitched a ride to get into the air. Here, a ground crew prepares to mate the X-1-3 to its mother ship, a B-50, in November 1951 for a captive flight.

As it would turn out, both aircraft were destroyed after the flight during defueling, according to NASA, and X-1 pilot Joseph Cannon was severely burned, requiring a hospital stay of nearly a year.

Altogether, 18 pilots flew the various X-1 planes. The X-1 measured nearly 31 feet long, stood almost 11 feet high, and had a wingspan of 29 feet. It weighed more than 6,700 pounds and carried nearly that much weight in fuel.

Convair XF-92A

The Convair XF-92A was the first delta-winged aircraft for the United States. The delta wing design had a number of advantages, including that it reduced drag and could be built thin while remaining strong. It was powered by an Allison J33-A turbojet engine.

Between 1948 and 1953, it flew more than 300 times for the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics (NACA, the predecessor to NASA), as well as for Convair and the Air Force. Only one airframe was built.

"Nobody wanted to fly the XF-92," NACA test pilot Scott Crossfield said. "There was no lineup of pilots for that airplane. It was a miserable flying beast."

X-2 in flight

X-2 skid

X-3 Stiletto

The distinctively slender Douglas X-3 Stiletto (only one was built) was active between 1952 and 1956. A rare bird among the X-Planes, it was designed to take off from the ground and under its own power. But early flights, NASA said, "showed that the X-3 was severely underpowered and difficult to control. Its takeoff speed was an astonishing 260 knots! More seriously, the X-3 did not approach its planned performance. Its first supersonic flight required that the airplane make a 15-degree dive to reach Mach 1.1. The X-3's fastest flight, made on July 28, 1953, reached Mach 1.208 in a 30-degree dive."

Still, the control problems for the X-3 helped researchers investigating similar problems with production model fighter jets, and its high-speed takeoffs and landings led to improvements in tire technology, according to NASA. And it was notable as well for its pioneering use of titanium.

X-4 Bantam

One of the more notable features of the X-4 Bantam, built by Northrop, was its semi-tailless design. That is, the tail section lacked horizontal stabilizers, so researchers could test a theory that those components were a key factor in stability problems at transonic speeds up to about Mach 0.9.

In the end, it was more like the opposite. "The X-4's primary importance involved proving a negative, in that a swept-wing semi-tailless design was not suitable for speeds near Mach 1. Aircraft designers were thus able to avoid this dead end," NASA said. Eventually, computer-driven fly-by-wire systems did allow for semi-tailless designs in production aircraft, such as the F-117 Stealth Fighter.

The two X-4 aircraft made a total of about 90 flights from 1948 to 1953.

X-5

The Bell X-5 gave NACA and Air Force researchers a chance to test out variable-sweep wings. In this case, the sweep of the wings could be shifted--in flight, no less--between 20 degrees and 60 degrees. The more swept-back the wing angle, the less the drag and the better for flight approaching supersonic speed. The powered transition took about 20 seconds, and, if needed, the pilot could hand-crank the wings into the more forward position (more perpendicular to the fuselage) for landing.

X-15 in flight

This is the X-15, which NASA calls "the most remarkable of all the rocket research aircraft." A total of three were built by North American Aircraft, and they set a number of speed and altitude records, going as fast as Mach 6.7 in October 1967 and as high as 354,200 feet, or 67 miles, in August 1963. The trio made 199 flights over nearly a decade, from 1959 to 1968.

Pictured here is X-15-2 after being launched from its B-52 mother ship. "The drop from the B-52 carrier aircraft was pretty abrupt, and then, when you lit that rocket a second or two later, you definitely felt it," X-15 test pilot Joseph Engle said in a NASA reminiscence.

The X-15 program was designed to provide insights into hypersonic flight (faster than Mach 5) as well as preliminary data on space flight. The aircraft were about 50 feet long and had a 22-foot wing span. The wedge-shaped vertical tail was 13 feet high.

X-15 test pilots

Meet some of the X-15 test pilots (there were 12 overall) in 1966, from left to right: Air Force Capt. Joseph Engle, Air Force Maj. Robert Rushworth, NASA pilot Jack McKay, Air Force pilot William "Pete" Knight, NASA pilot Milton Thompson, and NASA pilot Bill Dana.

Test pilots have a well-earned reputation for being cool under pressure, but even they feel some stress sometimes. According to NASA, during X-15 flights, the pilots' heart rates ranged from 145 to 185 beats per minute, well above the 70 to 80 beats during test missions in other aircraft up to that time.

For more, see "Photos: Looking back at NASA's X-15 aircraft."

Lifting bodies

The shifting emphasis in the X-Plane program to preparing for space flight continued with a series of aircraft known as "lifting bodies," a term that refers to more or less wingless planes that get their lift from the fuselage itself. Harbingers of the space shuttles, the lifting bodies were used to study how a similarly designed vehicle might re-enter Earth's atmosphere from space and then maneuver like an aircraft to a landing site.

Shown here are, from the left, the X-24A (which flew from 1969 to 1971), the M2-F3 (from 1970 to 1972), and the HL-10 (from 1966 to 1970). Altogether, the half-dozen different lifting bodies flew 223 times from 1963 to 1975, not counting some 400 flights made by the M2-F1 alone while being towed by a Pontiac Catalina convertible on the ground.

XB-70 Valkyrie

The idea behind the XB-70 Valkyrie was to lay the groundwork for development of a strategic bomber, but in the end, this X-Plane was used primarily as a test bed for potential supersonic transport (SST) aircraft for civilian travel. North American Aviation built two of the XB-70s, which together between 1964 and 1969 made 129 flights.

The design was intended for flight at Mach 3, but it proved less than ideal at that speed, and the two aircraft together logged less than 2 hours of Mach 3 flight time. Along with insights into handling at supersonic speeds, the XB-70 provided a great deal of information about sonic booms and other noise factors that would be important for commercial flights by supersonic aircraft.

X-29 in flight

You don't see many aircraft that look like the X-29, and for good reason--it's exceedingly hard to keep them stable. But using a computerized fly-by-wire system (in which electronic controls replace mechanical ones) and incorporating composite materials, the X-29 became, in NASA's precise phrasing, "the first forward-swept-wing airplane in the world to exceed Mach 1 in level flight."

The two Grumman-built X-29 aircraft flew from 1984 to 1992, making more than 400 total flights. This photo shows smoke generators at work, providing visual feedback to researchers about airflow over the X-Plane. The tufts along the fuselage and wings perform a similar function.

X-29 cockpit

The X-29 pilot had a lot to keep track of. So, too, did the aircraft's triple-redundant computerized flight control system, which kept close tabs on the flight conditions and would issue up to 40 commands per second to the control surfaces to maintain stability.

Says NASA about the flight control system: "Each of the three digital flight control computers had an analog backup. If one of the digital computers failed, the remaining two took over. If two of the digital computers failed, the flight control system switched to the analog mode. If one of the analog computers failed, the two remaining analog computers took over. The risk of total systems failure was equivalent in the X-29 to the risk of mechanical failure in a conventional system."

X-31

The X-31 was all about enhanced--even extreme--maneuverability for fighter aircraft. Even so, it improved flight safety because, in NASA's words, "it was fully controllable and flyable in the post-stall region, unlike other fighter aircraft without thrust vectoring." (The thrust vectoring involved three paddles, made of an advanced carbon fiber composite, on the engine nozzle at the rear of the aircraft, which could be moved to control the exhaust flow and thus allow adjustments in pitch and yaw.)

Built by Rockwell Aerospace, North American Aircraft, and Deutsche Aerospace, the two X-31 aircraft together made 555 flights in the first half of the 1990s. The fly-by-wire system used four digital flight control computers, but no analog or mechanical backup. "Three synchronous main computers drove the flight control surfaces," NASA says. "The fourth computer served as a tiebreaker, in case the three main computers produced conflicting commands."

X-36

Aircraft designers routinely use scale models, and in the case of the X-36 Tailless Fighter Agility Research Aircraft, that's as big as it got.

The 19-foot-long, remotely piloted X-36, built by Boeing's Phantom Works, is a 28 percent scale model that was created to test theories about the maneuverability and survivability of planes that lack a tail structure. Two were built, and together they made 33 flights in 1997 and 1998, including a pair of flights featuring Air Force Research Lab software that used a neural net algorithm to compensate for (simulated) in-flight malfunctions or damage.

X-38 release from B-52

Harking back to the lifting-body designs of the 1960s, the X-38 Advanced Technology Demonstrator was used to show the feasibility of what was intended to be a crew-return vehicle that would be based at the International Space Station.

To be used in the event of an emergency evacuation of the space station, the projected crew-return vehicle would re-enter the atmosphere like the space shuttle, and its life support system would have a duration of about seven hours.

Two prototypes were built by Scaled Composites, and they made about 15 captive and free flights between 1997 and 2001. At about 24 feet long and 12 feet wide, the pilotless X-38 aircraft were 80 percent scale models. The X-38 program was eventually canceled.

X-43 hits Mach 9.6

There are two things to know about the X-43A. First, it used an experimental engine called a scramjet, in which the supersonic speed of the vehicle itself compresses the air that the vehicle's engine, in turn, uses to generate hypersonic (faster than Mach 5) flight. In addition, the vehicle essentially surfs on the supersonic shock wave it creates.

Second, the X-43A flew really, really fast. One of the unmanned test vehicles reached Mach 6.8 (nearly 5,000 miles per hour) in March 2004, and the second reached Mach 9.6 (roughly 7,000 mph) in November of that year. By contrast, the manned SR-71 Blackbird, used for many years by the U.S. Air Force, had a top speed of just more than Mach 3.

X-48B

Another scale model, the 500-pound X-48B made its first flight in July 2007. This spring, the remotely controlled, Boeing-built aircraft, which features a "blended wing" body (wingspan: 21 feet), made its 80th flight as it completed the first phase of its testing.

Test flights are expected to resume later this year, after a new computer is installed. Unlike most other X-Planes, the X-48B isn't designed for supersonic flight; rather, it's meant to study ways to create quieter, more fuel-efficient aircraft.

X-37B

The more fevered imaginations have envisioned the vehicle as a potential weapon itself; more measured reaction has suggested that the X-37B could serve as a sort of quick-reaction surveillance satellite. The 29-foot-long space plane, much smaller than the space shuttles, can stay in orbit for up to nine months.

This photo shows the X-37B against the backdrop of the fairing that would encapsulate it for liftoff atop an Atlas V rocket.

X-51A

The hypersonic X-43A flew faster, but the X-51A flew longer. On May 26, 2010, the