Shocking "prison" study 40 years later: What happened at Stanford?

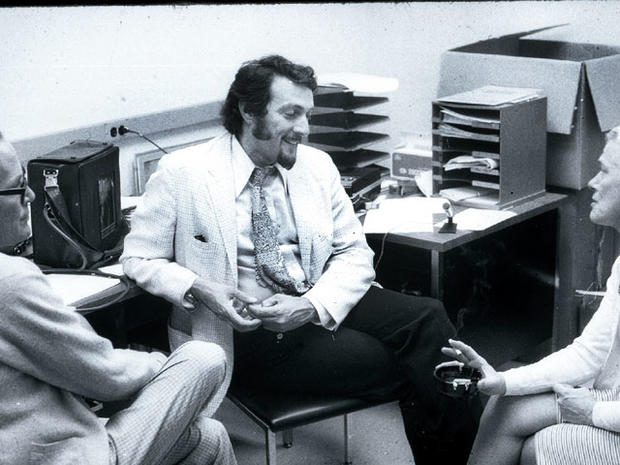

It's considered one of the most notorious psychology experiments ever conducted - and for good reason. The "Stanford prison experiment" - conducted in Palo Alto, Calif. 40 years ago - was conceived by Dr. Philip G. Zimbardo as a way to use ordinary college students to explore the often volatile dynamic that exists between prisoners and prison guards - and as a means of encouraging reforms in the way real-life prison guards are trained.

But what started out as make-believe quickly devolved into an all-too-real prison situation. Some student "guards" became sadistic overlords who eagerly abused the "prisoners," many of whom began to see themselves as real prisoners.

Just what happened in the basement of the Stanford psychology department all those years ago? Keep clicking for a glimpse back in time...

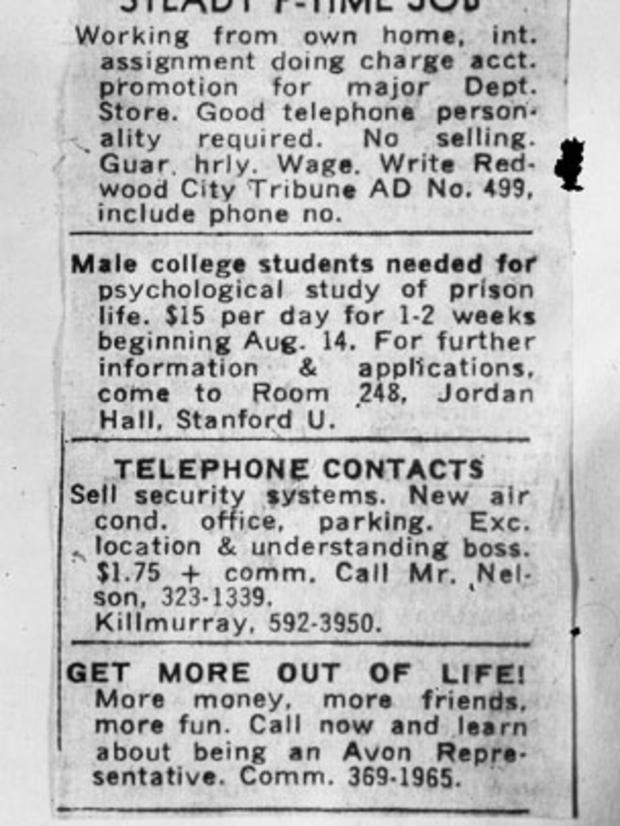

It all started with a newspaper ad: "Male college students needed for psychological study of prison life." Dr. Philip Zimbardo and his team selected 24 college students and offered them $15 per day for the two-week study. A coin-flip would decide who would be "prisoner" or "guard." Nobody, including Zimbardo, had any idea what was in store.

On a quiet Sunday in August, Zimbardo enlisted real Palo Alto police officers to help kick off the study - by arresting students from their homes for armed robbery. The idea was to make the experience as "real" as possible.

The students were read their rights, frisked, cuffed, then carted off to the Palo Alto police station.

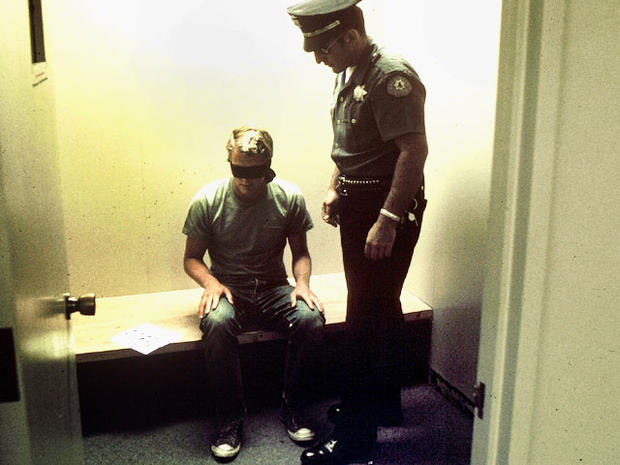

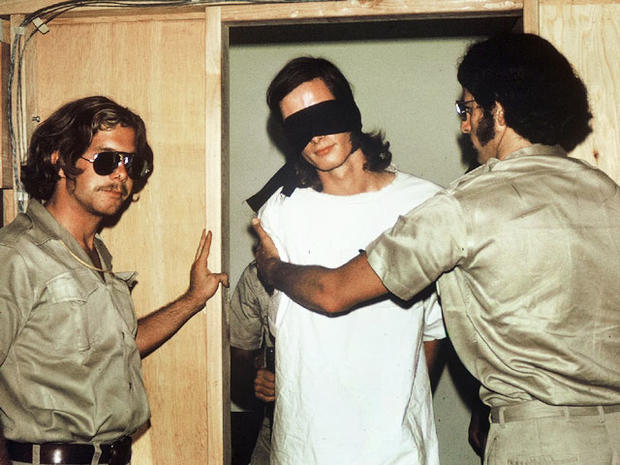

At the police station, "suspects" were fingerprinted, read their charges, blindfolded, and taken to a holding cell to await transportation to the "prison" at Stanford.

While the "suspects" were being rounded up by the real-world police, Zimbardo and his team put the finishing touches on the "prison." They nailed bars on cells and set up a closet for solitary confinement - known as "the hole." Real ex-cons served as consultants to make things as realistic as possible.

A hidden video camera was installed, and cells were bugged so the researchers could see and hear what was happening at all times.

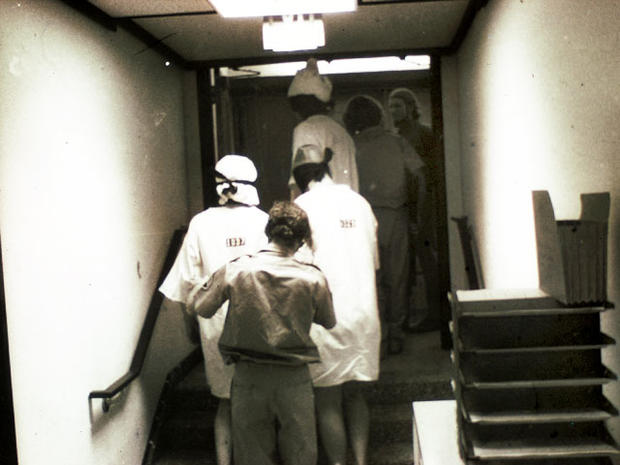

Many of the "prisoners" were still reeling from the surprise arrests when they arrived at the "prison." But things quickly grew even worse for the "prisoners," as they were stripped naked and "deloused" with a spray.

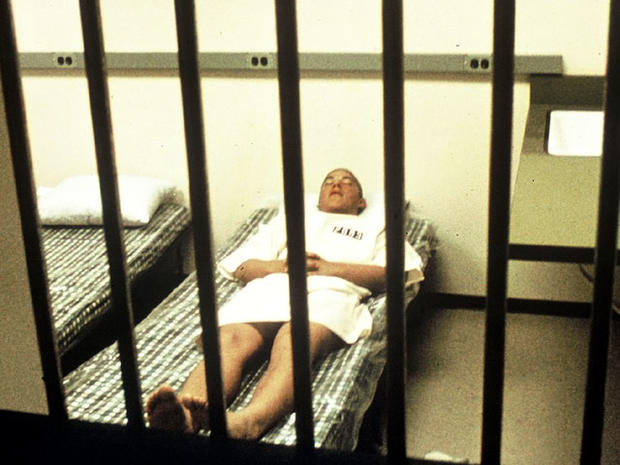

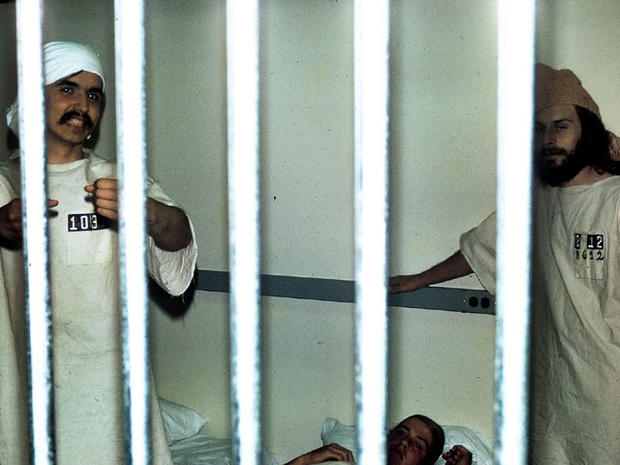

Each "prisoner" was issued a smock with ID number, stocking cap, rubber sandals - and each had a chain bolted to his ankle. The chain was to remind "prisoners" at all times that they were incarcerated and unable to escape.

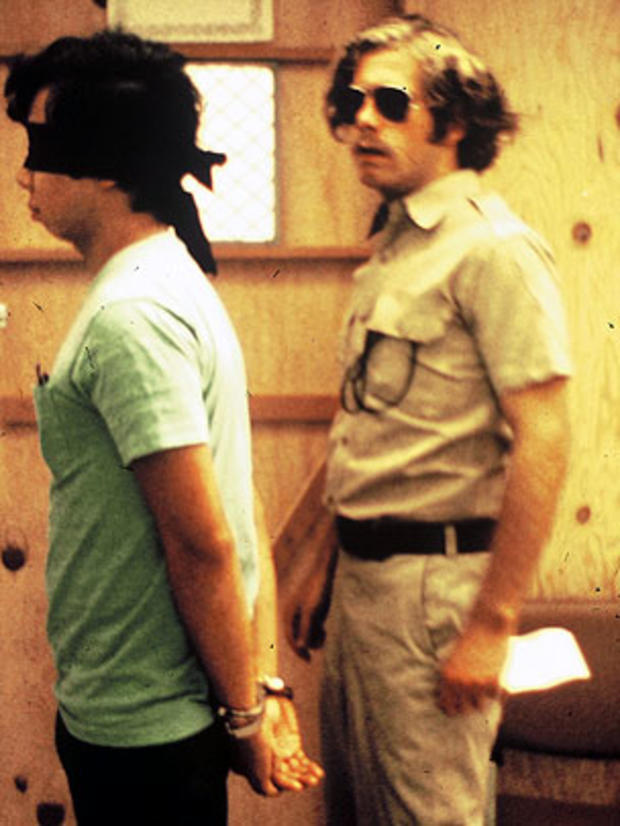

"Guards" wore khakis, mirrored sunglasses, and carried around a whistle and a baton. They were untrained, free to do whatever they deemed necessary to maintain law and order. Some played nice, but others grew increasingly sadistic.

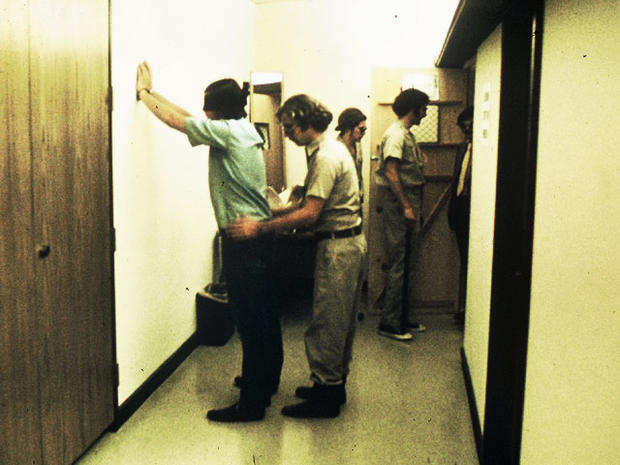

"Prisoners" expected some harassment and a poor diet when they volunteered. But they didn't expect to be rudely awakened at 2:30 a.m. the first night and forced to line up for roll call. "Guards" asserted authority by forcing "prisoners" to memorize their prison numbers and do push-ups.

On the second day of the experiment, the "prisoners" barricaded themselves in their cells, ripped off their numbers and caps, and began taunting the "guards." That surprised the researchers.

The "guards" responded by shooting fire extinguishes at the "prisoners," and then stripping the "prisoners" naked and removing their beds. "Guards" tossed the rebellion's leader into "the hole."

When the "guards" realized they couldn't always physically control their "prisoners," they turned to psychological tactics. The "guards" set up a "privilege cell" where the most cooperative "prisoners" got their clothes and beds back and were allowed to wash, brush their teeth, eat, and sleep.

Then the "guards" swapped the troublemakers into the "privilege cells," confusing everyone. The tactics made it hard for "prisoners" to trust one another."Guards" soon denied "prisoners" the right to use the bathroom, providing buckets. Emptying the bucket? That privilege was granted only to cooperative "prisoners."

"Prisoners" believed the "guards" were chosen because they were bigger and stronger. In reality, there was no height difference between the groups.

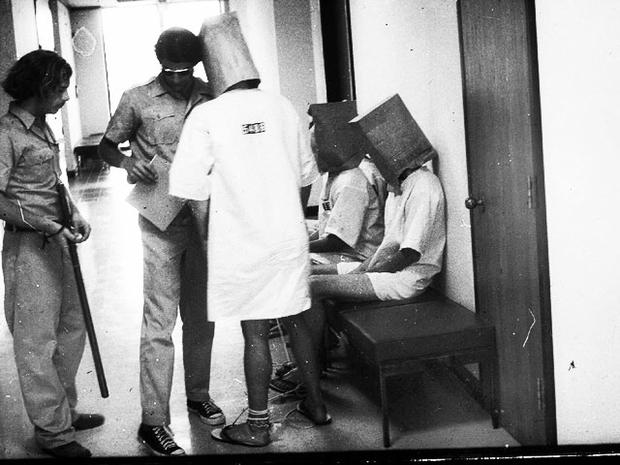

"Guards" put paper bags on the prisoners as they walked around - just one of many dehumanizing tactics.

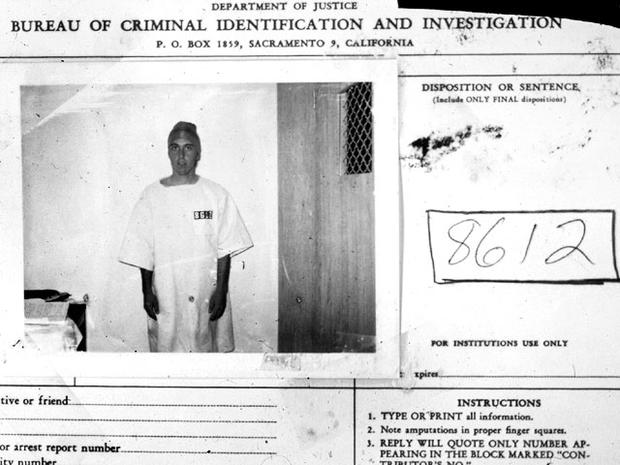

This "prisoner," No. 8612, went into a fit of rage less than 36 hours into the experiment, telling his fellow "prisoners" that they couldn't quit the experiment. It wasn't true, of course, but the message seemed to terrify the other "prisoners."

Zimbardo set up visiting hours with some of the "prisoners''" friends and family. He had the "prisoners" clean themselves and their cells, and fed them a big meal so worried parents wouldn't insist that their kids leave the study. Some parents nevertheless complained to Zimbardo - but he brushed off their concerns.

Rumors soon spread that prisoner #8612, who had been released following his outbursts, was arranging a prison break to free the "prisoners." When Zimbardo caught wind of the plan, he tried unsuccessfully to arrange for the "prisoners" to be transferred to a real prison. "Guards" blindfolded "prisoners" and led them to a different floor.

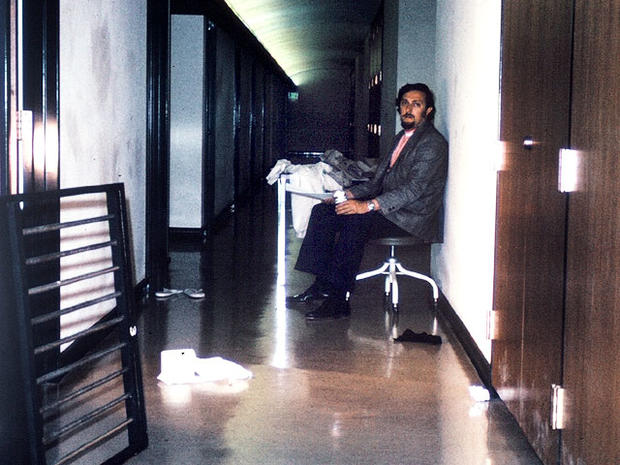

Zimbardo waited all night, but the prison break never materialized. Like his study's participants, Zimbardo seemed to have blurred the lines between reality and make-believe, by acting like a real-world prison superintendent.

After the rumored jail break, the "guards" escalated their harassment of the "prisoners." They upped the number of jumping jacks and push-ups the "prisoners" were told to do, and forced them to do unpleasant tasks, including scrubbing toilets.

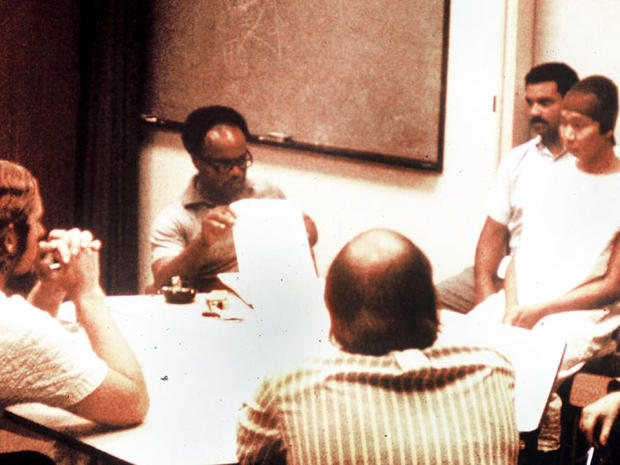

Zimbardo called in a priest to interview "prisoners," just as it might hapen in a real prison. To Zimbardo's amazement, "prisoners" introduced themselves to the priest not by their names but by their prison numbers.

When the priest asked "prisoners" why they were in jail, or if they needed a lawyer, some took him up on the offer.

More "prisoners" succumbed to the harsh conditions inside the "prison." One stopped eating and cried hysterically. Zimbardo told him he could leave the study, but he declined - saying he didn't want the others to believe he was a bad "prisoner."

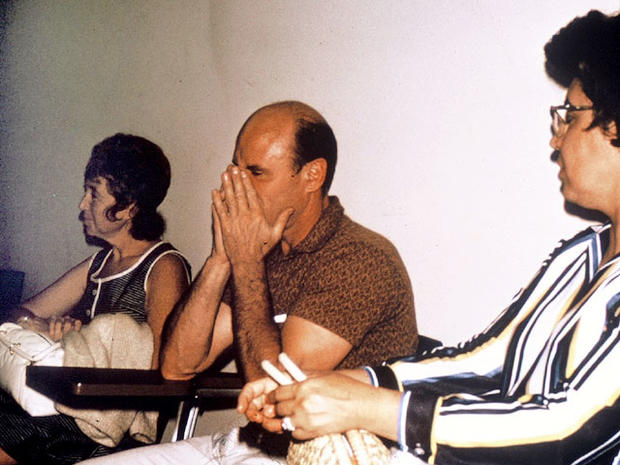

No prison experience is complete without going before the parole board. But this "board" was made up of psychology department secretaries and graduate students. They met with "prisoners" who thought they had grounds for parole. The "prisoners" seemed to forget that they could leave anytime they wanted. Said Zimbardo, "Their sense of reality had shifted."

Five days into the experiment, some "guards" calmed down and became "good guys." But others kept up their brutal treatment of the "prisoners," including one notoriously tough "guard" the "prisoners" nicknamed "John Wayne."

Parents eventually called Zimbardo, asking if they could contact a lawyer to get their kids out of "prison." The calls, combined with the increasingly abusive treatment of the "prisoners," convinced Zimbardo that the experiment had gone too far. But Zimbardo ended the experiment only after being admonished by a newly minted PhD who had returned to Stanford and was shocked by what she saw.

The experiment was certainly shocking, but did it bring about the sorts of prison reforms that Zimbardo had hoped for? Not really. "Research and knowledge rarely changes systems," Zimbardo told CBS News in an email.

But the experiment has been cited again and again over the years - for example, by experts trying to explain the 1971 riots at Attica Correctional Facility in New York, or even the dehumanizing photos that came out of Iraq's Abu Ghraib in 2003.

What's more, as Zimbardo points out, just about everyone fills the role of "prisoner" or "guard" at some point in their lives - as when a boss restricts the actions of his/her subordinates or a parent disciplines a child. And it's in these roles that we live up to - or down to - our own expectations. As Zimbardo puts it, "Human behavior is under situational control more than we imagine or want to believe and admit."