San Francisco's War Stories

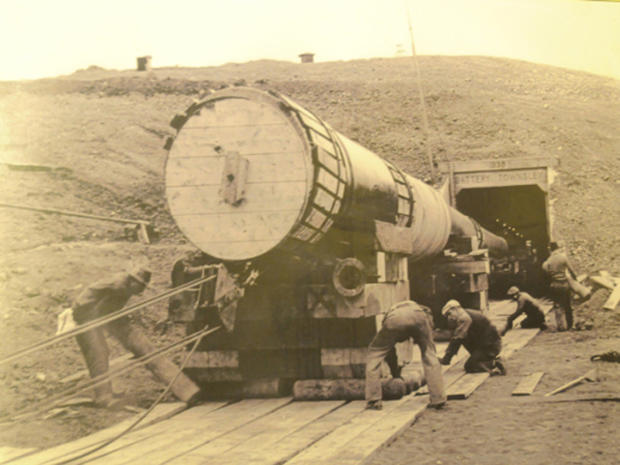

"Fort Point was built between 1853 and 1861 by the U.S. Army Engineers as part of a defense system of forts planned for the protection of San Francisco Bay. Designed at the height of the Gold Rush, the fort and its companion fortifications would protect the bay's important commercial and military installations against foreign attack. The fort was built in the Army's traditional 'Third System' style of military architecture (a standard adopted in the 1820s), and would be the only fortification of this impressive design constructed west of the Mississippi River. This fact bears testimony to the importance the military gave San Francisco and the gold fields during the 1850s."

Yet while many people never knew about that history, or had long forgotten it, the relics of a century of coastal fortifications are still very much in evidence in and around San Francisco.

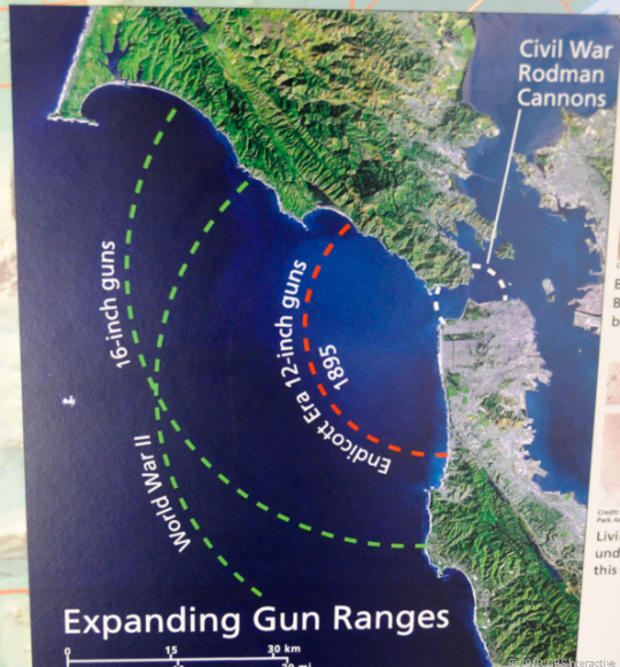

Today, San Francisco is thought of mainly as a picturesque tourist destination. But for decades, it was considered America's most valuable Pacific port and was home to a wide variety of military installations. As a result, military planners put a huge amount of energy, starting in the Civil War era, into protecting the Pacific coast from invasion or attack.

And that's why there is a treasure trove of old batteries and other remnants of original fortifications up and down the coast in and around the city.

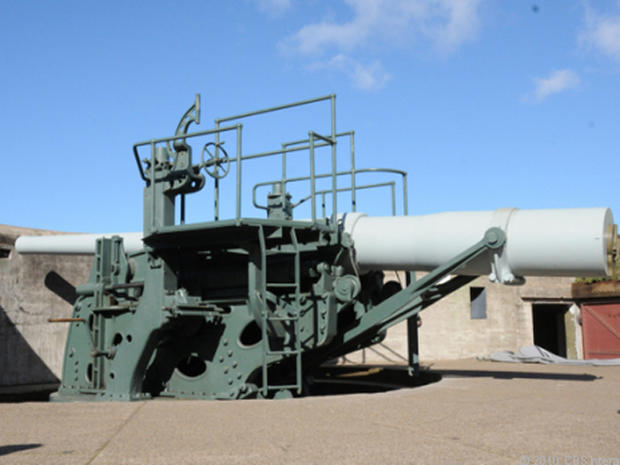

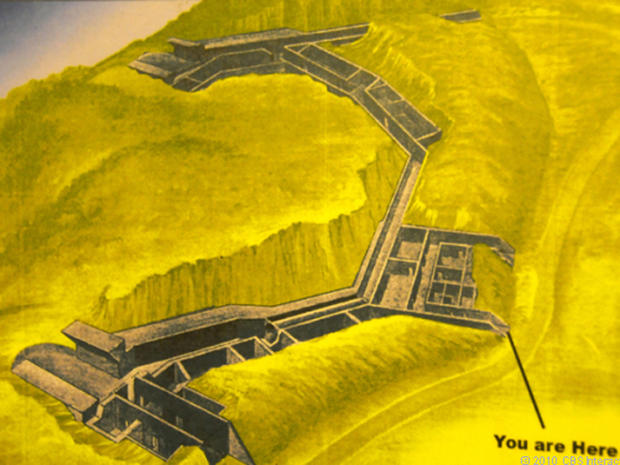

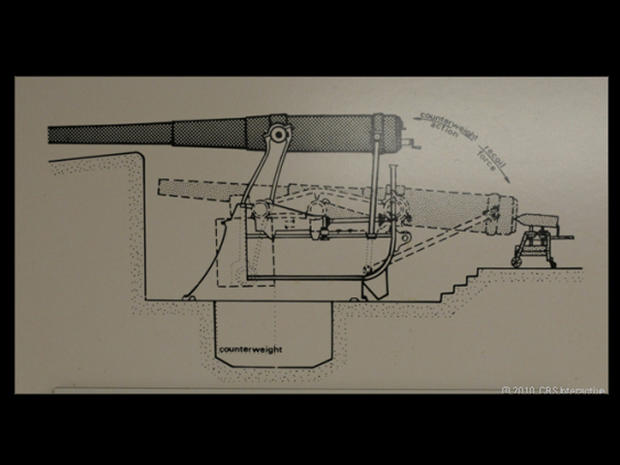

This is a 6-inch disappearing gun that is mounted at Battery Chamberlin, in the shadow of the Golden Gate Bridge, in San Francisco. This battery was meant to protect some of the city's most exposed beaches from direct attack from the open Pacific Ocean. The gun, while an original, was placed at Battery Chamberlin in the 1970s, when the site was opened to the public as a museum.

It was called a disappearing gun because it was meant to be housed low to the ground and invisible to the sea, and was raised up only when firing. When it would discharge its six-inch shell, it would recoil back down low to the ground. The idea was to protect the gun itself from attack, and to keep the lowest possible profile.

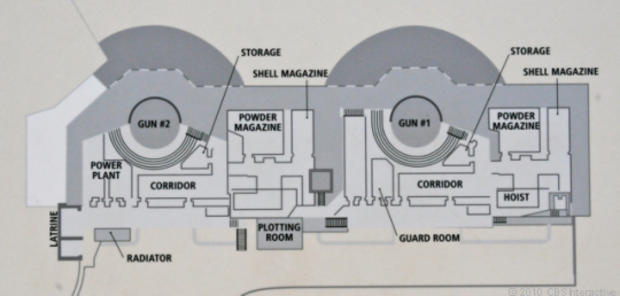

In 1917, Battery Chamberlin was temporarily decommissioned because World War I was nowhere near the Pacific Coast, and the U.S. Army needed its troops in Europe. But in 1920, the battery was re-commissioned with two 6-inch guns like this one, each of which had a 10-mile range, and which had a maximum rise of 15 degrees.

It took 25 men to operate each of the guns, and the Army installed bunks nearby so that crews could work week-long shifts.

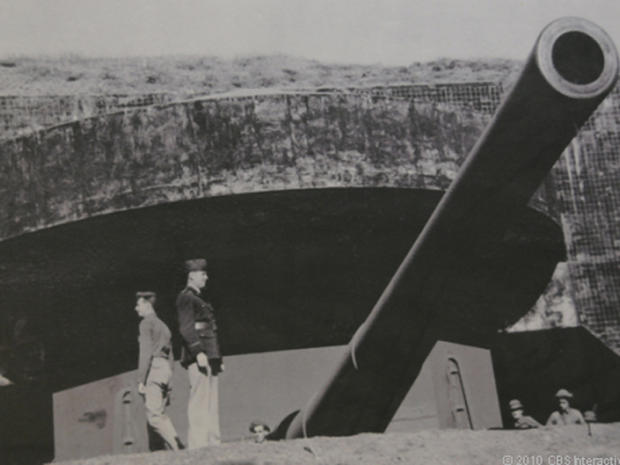

The gun areas were covered by giant cement casemates intended to protect the guns from aerial attack. One of the big guns was mounted here, though it has long since been taken away.

The National Park Service is trying to weigh the balance between allowing the public to visit these sites, and the potential danger of damage to delicate areas of having thousands of people walking through.

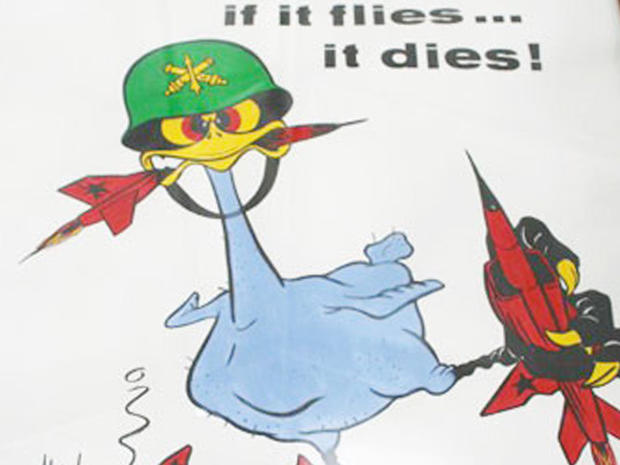

These missiles were seen as a last line of defense against nuclear bombers with which the Soviet Union might have attacked the U.S. during the Cold War.

This Oozlefinch is from the Nike missile site in the Marin Headlands, but another Oozlefinch can be found inside Battery Townsley, which is close by the Nike site but which protected the Pacific coast during World War II, rather than during the Cold War.

"Battery Mendell was designed for 'disappearing guns' that rose up for firing and then dropped back down behind the protective parapet. That ensured greater cover for both the weapons and troops than older batteries had provided. However, new technology, such as that employed at [the] nearby Battery Wallace...soon enabled high-angle fire. This near doubled the distance guns could shoot."