Portraits of Holocaust survivors

Since 2009, Nabrdalik has interviewed and photographed 45 survivors. He has gathered their portraits and memories into a book, "The Irreversible," and an exhibition of the work will open at VII Gallery in Brooklyn, N.Y. on Sept. 12, 2013. Read on to see selections from this work and learn more about the project here.

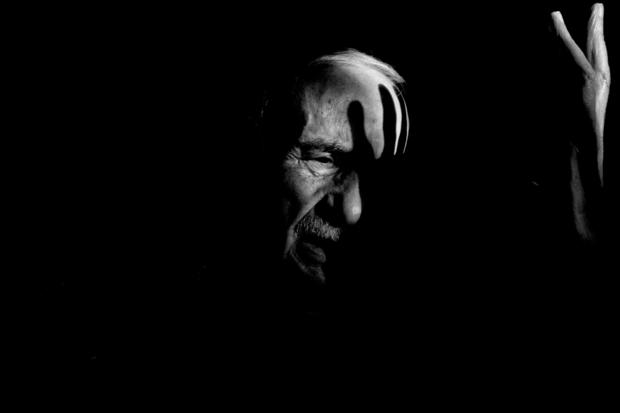

In this photo, Jakob Rotenbach, KL Auschwitz-Birkenau and KL Mauthausen-Gusen survivor

"After the war, nobody wanted to listen to the stories about the camp, so I would talk to the wall. Later, it was announced that the camps had never existed. I couldn't remain silent. I spoke with students, I took part in conferences, and I was active in the Auschwitz-Birkenau Foundation. When my four or five-year-old grandchildren asked, pointing to my tattoo, 'What is it?' I explained to them where it had come from. People would tell me that I was crazy, that I shouldn't talk about such cruelty with small children, but I couldn

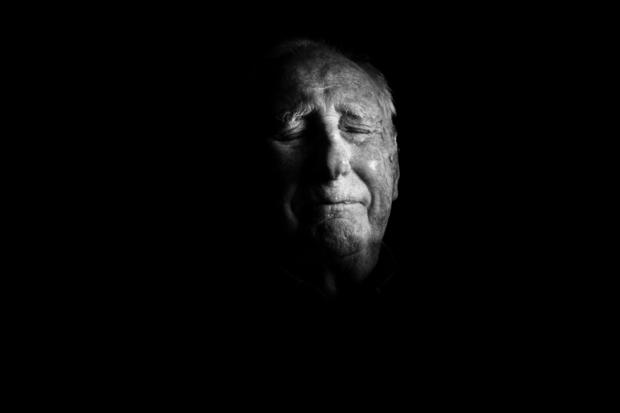

Danuta Bogdaniuk

"After he smeared something all over my head, only bare skin was left and all my hair fell out. I started crying because I thought that it wouldn't grow again. But it grew and my hair has been exceptionally pretty ever since. And it's not dyed. I have never dyed my hair and I'm 75 years old. Even though it is not the color that suits me best."

He smeared me with something there, in Auschwitz. Some German. Nobody said anything, so how was I to know that it was an experiment?

I do have beautiful hair, don't I?"

Felix Gutmacher

"It was impossible not to notice how beautiful Frieda was. Everyone admired her. The commanding officer at a transit camp in Malines made a proposal: if she became his lover, he would free her parents. If she refused, all three of them would be put on the next train to Auschwitz.

She answered with no hesitation: 'We'll wait to get deported.'

That day I prayed to be on the same train with her. I was impressed that this woman, brought up in comfort, displayed such courage. She became much closer to me as a result of her decision. We were brought to Auschwitz and separated there. Months passed and I couldn't stop thinking about her. I was afraid that if we met, we might not be able to recognize each other as the people we were before the camp. I was hoping, though, to see her smile one more time.

After I returned to Brussels, I found out that Frieda and her parents had been gassed right after their arrival in Auschwitz. I mourn her until this very day."

Maria Brzecka Kosk

"The camp in Buchenwald was run very strictly. Its commandant was a man who had lost an eye in a war in Russia. We called him Wolf. He could shoot a woman running to the restroom in the evening, or tie a Russian woman to a pole during an assembly and whip her just because she had stolen one potato.

Our camp was surrounded by ammunition factories where women worked in two shifts. My mother and I labored at night. We had to operate two two-meter-high machines. I would stand by them on tiptoes. When we were taken to the restroom, I would immediately sit down - my legs hurt so much.

My mother knew a little German and asked a female guard to treat me a bit more gently since I was only a child. On the fourth day the guard took pity on me and asked me to follow her to the block. I obeyed happily. I immediately climbed up onto the bunk and fell asleep. After a little while I heard the attendant calling out my number. I woke up, jumped down, and saw the commandant standing in the door.

He was furious. He said he was taking me with him because I had run away from work. He left first and I followed him. We walked toward the blocks. He told me to stand against a wall and he stood against the other one. He took out his gun and aimed at me. At that moment something strange happened with me. I stopped thinking about what he was doing. I felt excruciating pain from my stomach up to my throat. My whole body ached, and the only thing I was thinking was: 'God, which is the glass eye and which is the real one?' I started walking towards him slowly, looking him straight in the eye. Step by step. When I was very close, he lowered his hand."

Marian Marczak

"My uncle came up with a plan: 'I'll go in first and say 'hi' to your mother as usual. She will want to offer me dinner because it's been a while since we saw each other. I will ask whether her husband or son returned, whether she has had any news. And you will wait in hiding.'

I'm waiting by the door and hear my mother saying that she doesn't know anything about us. And my uncle says: 'And if Marian showed up, what would you do?'

She answered, 'I don

Alicja Hintz-Zdybska

"I was twelve in 1944. I appeared to be no more than eight. In Auschwitz I ended up in a children's block. My mother was placed right next to us, in a women's block. She was continuously ill and I kept losing sight of her. Nobody told me anything, nobody pointed to any place where I should look for her. I would search and inquire about her all by myself. Somehow I managed to find out that my mother was in the hospital block, in the so-called gypsy gulag. I had this idea that I would sneak out after dark and find her. I walked on, hiding behind the blocks. I was very lucky that no German soldier shot me on the way.

I reached the rear of the camp hospital, but I couldn't get in -- on the path leading to the door there was a pile of corpses. They were the bodies of the dead thrown out every day behind the block. Tens of skeleton-thin corpses bent in different ways, with different expressions on their faces. It was the first time I had seen a dead person. I didn't dare to step on these bodies. I had to move all these corpses aside with my own hands. The whole pile bigger than me! I dragged the corpses by their legs and arms, I moved their heads aside. It was winter and I didn't have gloves.

I found my mother on one of the bunks. She was squatting with her knees under her chin, shivering; she didn't recognize me. I started crying loudly and then I heard a female voice: 'Is this your mom?'

'Yes! But she doesn

Baron Paul Halter

"I was arrested in the street because I resembled a man wanted by the Gestapo for his underground activity. I was supposed to be shot but the officers decided that, as a Jew, I should be transported to the camp. I survived because I was sent to Auschwitz! What a paradox. A miraculous salvation!

I continued to be active in the camp resistance movement. Our solidarity not only boosted our morale but it also increased our chances for survival. The newspapers we read aloud to other prisoners were the same ones that later protected us from the cold. When I came down with tuberculosis, my friends secured medications for me. I think that we were all bound by the unspoken, unconscious desire for survival and for speaking the truth about the camps -- so that the novelists and historians would not have to make things up.

It was harsh winter, 13 degrees below zero. Shortly before the camp was closed down, all the prisoners were called in for a roll call. One prisoner was too exhausted to take his cap off fast enough in front of the SS man. They poured cold water all over him and the rest of us watched him freeze to death."

Marian Plackowski

"Throughout the spring, until the liberation, Americans kept bombing the Linz metal plant that we had been clearing of debris. You know, before Americans can take over any territory, they have to raid everything. They carried out the last bombing a week before they entered and the last missile landed exactly where I was standing.

The next day, Austrian workers with the prisoners' help pulled dead bodies out of the rubble. I was unconscious when they dug me out, but they realized that I was alive and took me away from the camp to a small hospital run by nuns.

A week later, when the Americans took over the camp, they took me to their field hospital. The treatment took one year. First they bombed me and then they cured me, though my left shoulder is still out of order because of the shell fragment. I walk around crooked, with my numb hand, and everyone thinks that I have suffered a stroke."

Sabina Nawara

"We were working outside the camp, by the fish ponds. Our job was to clear them of bulrush -- we had to get into the water and take this awful weed out. It was late fall and the girls did not want to get wet. When my good friend refused to go into the water, our supervisor pushed her to the ground, put the spade on her neck, stepped on it, and strangled her. After that, no one else was afraid to get in.

I got arthritis because of it and one day I was in bed in the camp hospital while the selection was going on. The doctor came in and told all of us to leave our beds. I couldn't move so he wrote down my number and directed me to block 25 -- the block from which you were sent to the gas chamber.

I was carried there and spent another three, maybe four days in bed. We were already without clothes, naked, and without bed sheets when the block doctor called out my number. I didn't respond. She read it again and I remained silent. A friend lying right next to me said: 'Listen, this is your number.' And I replied: 'It is obvious what she wants from me. It's better to keep quiet.'

The doctor approached me, verified my number, and said: 'That's right! I'll be right back and I will carry you to the regular camp hospital.' And I said: 'Do you think I don't know where I will be taken?' She told me, 'No, they don't burn Aryans today.'

And that was true. The four of us were taken back to the camp hospital."

Tola Grynholc Urbach

"There were twenty two camps in tiny Estonia.

Only me and my sister survived.

We got out of the camp and we saw something incredible -- hundreds of empty cases of vodka bottles. I guess Germans needed alcohol in order to carry out their work

Wanda Ojrzynska

"We knew that they were on their way toward death, but we didn't yet know exactly how it happened. I vividly remember that there was in the camp a well-known Hungarian violinist, a Jewess. The Germans told her to give a concert for the staff in the washrooms, close to the ramp and the chimney. We weren't working that day and when we found out about her show, we went to listen to the performance.

We couldn't get inside even though the door was open. She kept playing truly magnificent pieces and the cars transporting people passed right next to us. These people did not know what awaited them and kept waving to us. It was macabre. You couldn't tell them anything; what would you say anyhow? And I couldn't bring myself to wave back either."

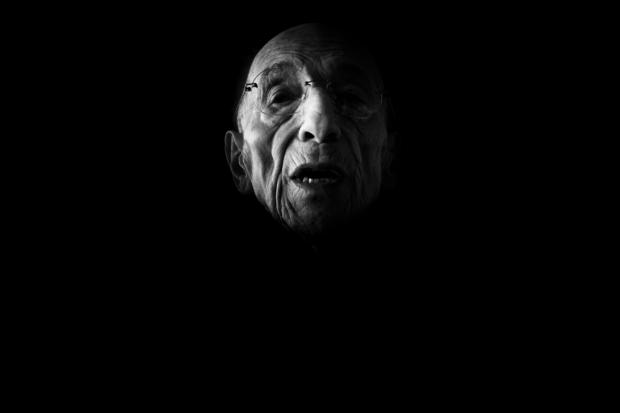

Roman Kent

"I think you can divide the camp survivors into two categories. One group would say: 'God wanted me to survive.' And in this way their faith in God is stronger. On the other hand you have people who would say: 'If God is what we believed he was, he must have been in Auschwitz. And how could he allow children, little children, to be killed? Where was God then?'

I believe in the goodness of men. I judge people not by their religion, but by who they are and how they act. And if we speak about religions, I would like to add one more to the Ten Commandments. The 11th commandment should be: 'When you see evil, do something.' Most evil things happen when people are bystanders, when they do nothing. And then evil can prevail even if it's done by a small group of people. The Righteous are the moral example of what could have been done, but what the humankind failed to do."