Lamar Johnson's 28-year fight for freedom

Lamar Johnson was convicted of Markus Boyd's murder in 1995. He always insisted he was innocent, but it would take almost three decades for a court to agree.

On Feb. 14, 2023, in front of a packed St. Louis courtroom, Lamar Johnson became a free man. Judge David Mason exonerated Johnson after he spent 28 years behind bars for a murder he did not commit.

The scene of the crime

On the night of Oct. 30, 1994, in St. Louis, Missouri, Markus Boyd was sitting on his front porch, talking to his friend, Greg Elking, when two masked gunmen ran up to them. Boyd was shot and killed, but Elking was spared. The men vanished and Elking ran off.

Who shot Markus Boyd?

When investigators began looking into the shooting, they spoke with Boyd's girlfriend. She was in their apartment upstairs with their daughter when the shooting occurred. According to investigators, she told them that a man named Greg was on the porch with Boyd. And when they asked her who she suspected did this, she mentioned Lamar Johnson, a longtime friend of Boyd's who she thought recently had a falling out with him.

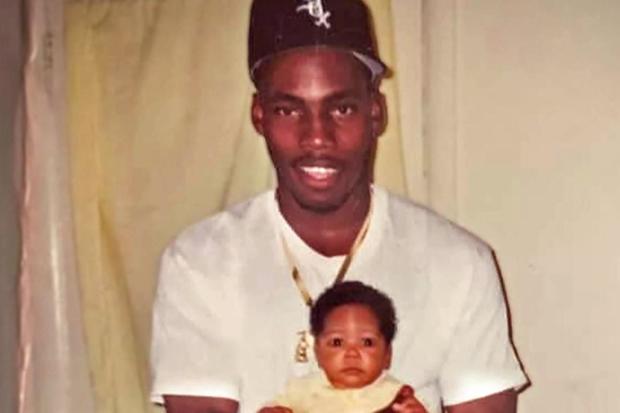

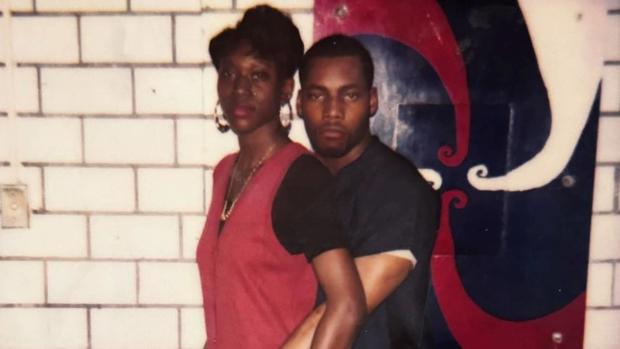

Who is Lamar Johnson?

Lamar Johnson grew up in St. Louis. In 1994, he was a 20-year-old father of two. He worked at Jiffy Lube while attending community college in St. Louis. But he also had a dangerous side hustle — selling small amounts of crack cocaine to make extra money.

Three miles away

Johnson says he was at a friend's house about three miles away with his girlfriend, Erika Barrow, and their 5-month-old daughter when the shooting happened. Barrow says that Johnson only briefly left the house once to make a transaction. Barrow, who was changing their baby's diaper when Johnson left, says he was back as she was finishing and cleaning everything up. Minutes after Johnson returned to his friend's house, he got a call that Boyd was shot. The next day, Johnson learned Boyd was dead.

The lone witness

Greg Elking was the only witness to the shooting. Elking and Boyd both worked at a printing company and had soon become friends. Boyd also sold drugs and Elking was one of his customers. On the night of the shooting, Elking was looking to get high but didn't have enough money. He says he brought an answering machine to make a trade, but Boyd didn't want to sell him the drugs. Boyd reminded Elking that they had work the next day. When Boyd was shot, Elking ran in terror.

Finding the witness

After learning about Elking from Boyd's girlfriend, investigators tried to reach the only eyewitness to the murder, but he was scared to come forward. He was still reluctant when he reached out four days later, but that changed when he met the lead detective, Joe Nickerson. "I thought he was straight out Nick Nolte from "48 Hours" — out of a movie — he was awesome," he told "48 Hours."

What he saw

Elking says he told Nickerson that the two gunmen were wearing dark masks similar to this one. He could tell they were dark-skinned Black men, but he only saw the eyes of one of the suspects through the masks. The shooting also occurred at night and on a dimly lit street, making it more difficult to see clearly.

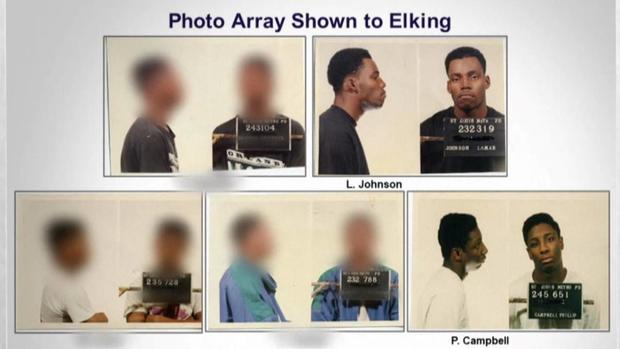

The photo array

Even though Elking said he didn't get a good look at the suspects, he says Det. Nickerson insisted on showing him an array of several photos. Elking said one of them stood out because of the eyes. The photo was of Lamar Johnson. Elking says Det. Nickerson asked him to sign the back of it, but he refused. "Because I didn't want nothing to do with this, because I couldn't pick out no murderer," he told "48 Hours."

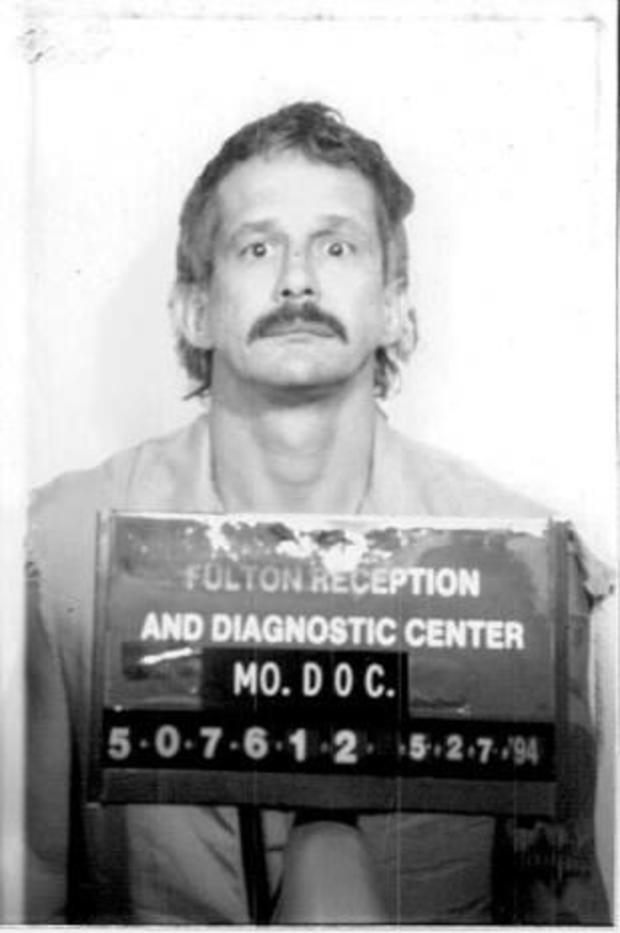

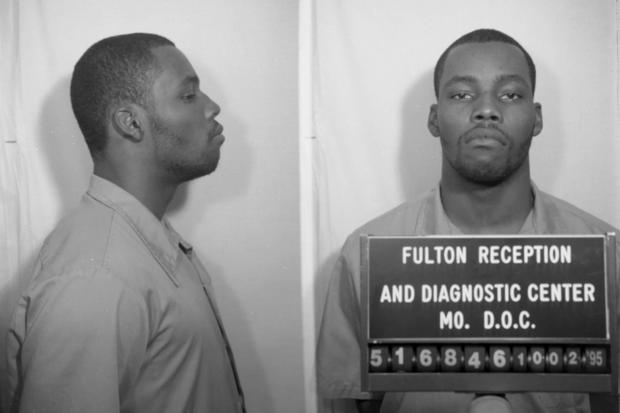

The arrest

With a name from Boyd's girlfriend and with what they considered a photo identification from Elking, investigators felt they had a reason to focus on Johnson. On Nov. 3, 1994, four days after the murder, Johnson was giving his friend, Phillip Campbell, a ride home. Officers pulled over the car and arrested both Johnson and Campbell.

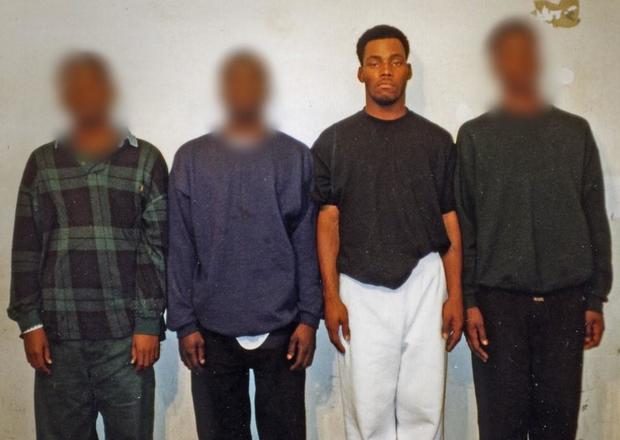

The first lineup

At the police station, Johnson agreed to do a photo lineup. He is in the third position, wearing the white pants. Det. Nickerson brought Elking in to try and make an identification. Elking viewed the lineup twice and didn't make an identification. On the third viewing, Elking identified the person in the fourth position, who was a filler from the jail and not one of the shooters.

The second lineup

Elking was then asked to view a different lineup. Johnson was not in this one but the other suspect, Phillip Campbell, is in the fourth position. Elking was unable to make an identification.

After the lineup

Elking says that after he struggled with the lineup, he felt like he let Det. Nickerson down. According to Elking, he told the detective, "You tell me what the numbers were, and I'll tell you if they were correct." He says Det. Nickerson replied with three and four. "And I was like, you're right, three and four." Nickerson denies these claims. He declined "48 Hours"' request for an interview, but sent us a text saying in part, "I went where the facts, evidence and circumstances took me."

The prosecutor

Dwight Warren, the original prosecutor in this case, says he pressed Elking on his identification of Johnson. Elking said he was telling the truth, so Warren charged both Johnson and Campbell. In July 1995, Johnson went on trial, with Elking as the star witness.

The jailhouse informant

To help bolster the prosecution's case, one of their witnesses was William Mock, a jailhouse informant with a lengthy criminal history. He testified that he overheard Johnson and Campbell in a holding cell talking about the murder.

Warren says he checked out his claim. "He was in two jail cells away. He was in a position that, to be able to hear that," Warren told "48 Hours." Johnson's attorney, Lindsay Runnels, says Mock wasn't credible.

Guilty

Lamar Johnson didn't take the stand at his trial. The defense put his girlfriend, Erika Barrow, on the stand. She told the jury Johnson was with her at the time of the shooting. The jury came back with a guilty verdict after less than two hours. In September 1995, Lamar Johnson was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

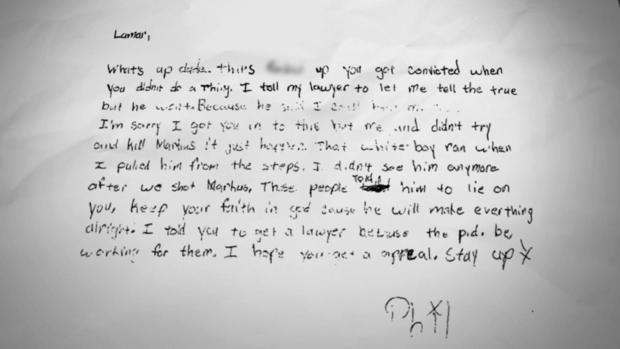

"You didn't do a thing"

Between Johnson's trial and sentencing, he exchanged letters with the other suspect, Phillip Campbell. It was in those letters that Campbell admitted that Johnson was not involved. In another letter, he even named the other shooter: James "B.A." Howard. Johnson tried to get a hearing about this new piece of evidence, but his request was denied.

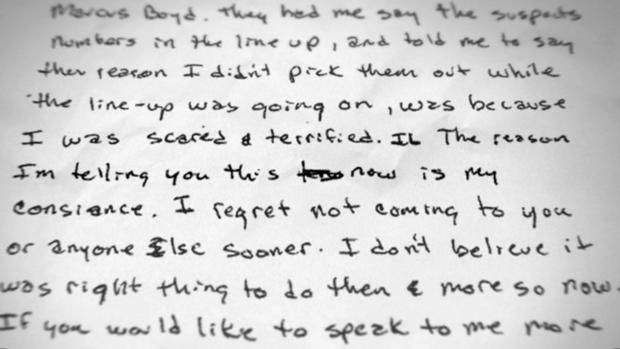

Greg Elking's letter

With legal help, Johnson filed a motion for a new trial, but it was denied.

Years later, the Midwest Innocence Project took on his case. In their research, they discovered new evidence. In 2003, the star witness, Elking, then in prison for bank robbery, had written a letter to a clergyman admitting he lied at Johnson's trial.

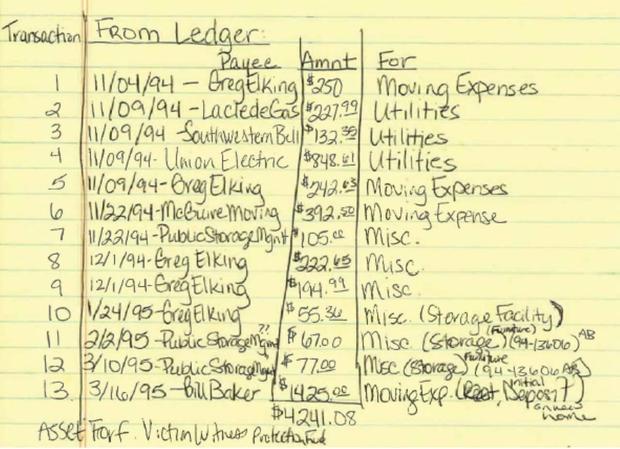

The payments

In the letter to the clergyman, Elking also revealed that law enforcement said they could help him financially and relocate his family. Detective Nickerson and the prosecutor's office had put him in the witness protection program. Elking's debts were paid, and his outstanding traffic warrants were cleared. Altogether, Elking received more than $4,000 in payment, seen in this ledger. None of this was revealed to Johnson or his attorney at trial, and the jury also never heard about it.

The Circuit Attorney

In 2018, St. Louis Circuit Attorney Kimberly Gardner agreed to look at Johnson's case. She had created a Conviction Integrity Unit to look at cases of possible wrongful conviction. When her team looked deeper, they found more red flags. One of them was that the jury never heard that the jailhouse informant was a racist with a hatred for black people, nor did they hear the majority of his criminal record. Another flag was the timeline presented at trial.

The drive

Detective Nickerson testified at Johnson's trial that Johnson could've driven from his alibi's house to Boyd's apartment in five minutes, even though it was about three miles away.

"48 Hours" correspondent Erin Moriarty tested out the drive with an investigator from the St. Louis Circuit Attorney's Office. It took about 13 minutes just one way. Johnson's girlfriend at the time, Erika Barrow, says there's no way that Lamar had left her sight for that long that evening.

Searching for hope

For years, Johnson requested hearings to present this new evidence, but was repeatedly denied. With the help of the Midwest Innocence Project and the St. Louis Circuit Attorney's Office, Johnson hoped a judge would hear his case. But even though Gardner was convinced Johnson was innocent and tried to get his conviction overturned, court after court, including the Missouri Supreme Court, said she didn't have the power.

Hope

In 2021, the Missouri Legislature passed a law that gave Gardner and other prosecutors the power to bring cases of innocence to the court. A year later, Johnson received the news he had been waiting to hear for 28 years — he would finally get a hearing to present new evidence in his case.

The real shooter

The week-long hearing began on Dec. 12, 2022, in a St. Louis courtroom. After opening arguments, Johnson's team called their first witness: James Howard. While on the stand, Howard, who is serving a life sentence for a different murder, admitted he was one of the men who shot Markus Boyd.

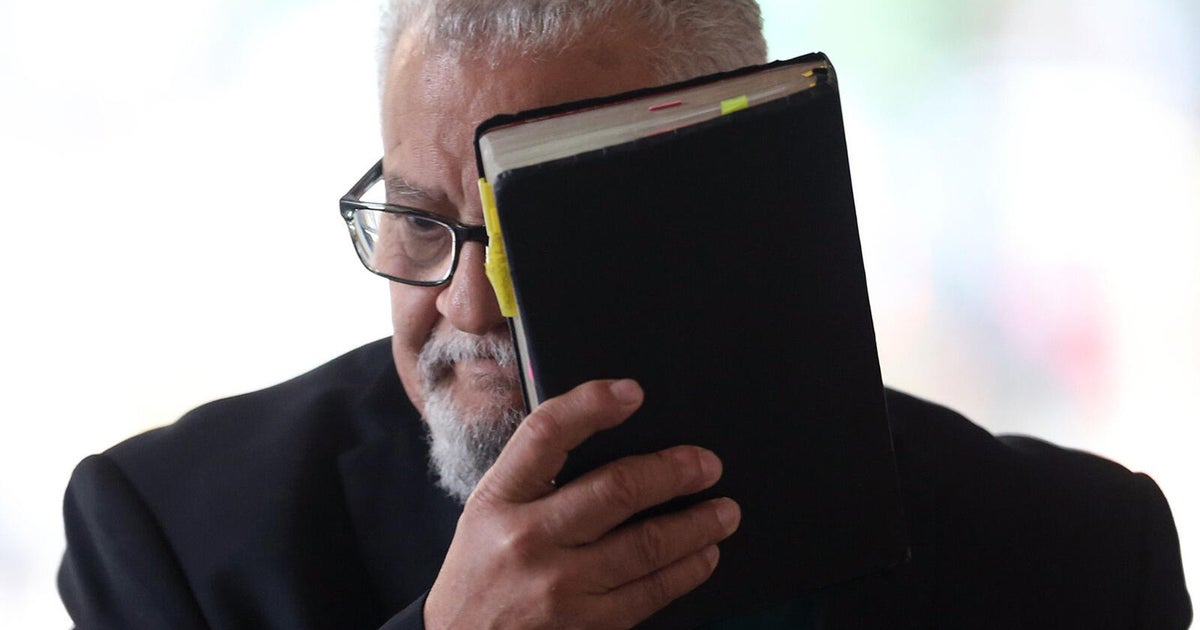

The former star witness

Greg Elking was called up next to testify. He told the court that he felt pressured by Det. Nickerson to identify Johnson in the lineup. "And I've been living with it, 25, 28 years and I'm telling you … I just wish I could change time," Elking said on the stand.

Lamar Johnson speaks

On day four of the hearing, Johnson took the stand. He finally got to defend himself and assert his innocence in front of the judge. The prosecution asked him about his conversation with Det. Nickerson a few days after the murder. Johnson said he voluntarily participated in the lineup because he didn't think he had anything to lose. "I didn't commit the homicide. So why would I be concerned that I had everything to lose?"

The detective

After Johnson's testimony, the State's Attorney called their first witness, Det. Joe Nickerson. He denied pressuring Elking to identify Johnson. "Mr. Elking goes …'hey, I know who it is, it's number three in the first lineup and it's number four in the second lineup,'" he stated. The State's attorney asked if he told Elking to say that. Det. Nickerson replied, "I didn't tell him to say anything."

The judge

Judge David Mason listened intently each day of the hearing. He even took over the questioning from the lawyers at points, making it clear when he believed something and when he didn't. After five days of testimony, Johnson's freedom was in Judge Mason's hands. Johnson waited in a St. Louis jail, hoping for the best outcome.

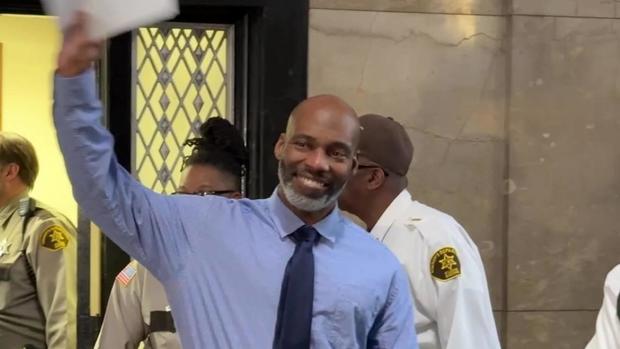

Exonerated

Judge Mason called everyone back to the courtroom on Feb. 14, 2023 – about two months after the hearing ended. His decision was made. After finding clear and convincing evidence of Johnson's innocence, Judge Mason overturned the conviction. Johnson was fully exonerated. Johnson finally got his wish and walked out of that courtroom a free man.