Killer whales

The orca is beloved by many. Many Americans, in particular, came of age watching the "Free Willy" films and attending the popular Shamu Shows at SeaWorld. Killer whales have long been the subject of fascination. In recent years, however, they have also become the subject of much debate, as news reports and critically acclaimed documentaries examine the potentially averse effects of captivity on these majestic animals.

So, how much do we really know about them?

40 peas in a pod

Killer whales hunt in deadly groups of up to 40 animals, called pods. Within these groups, they utilize cooperative hunting techniques, like those of wolf packs.

Pods on the hunt

There are two types of orca pods: those with resident populations and those with transient populations. And the population of the pod tends to determine what it hunts.

Resident pods generally hunt fish, while transient pods have been known to hunt everything from seals and sea lions, to penguins and blue whales. Orcas in New Zealand even eat stingrays. That's a pretty mean diet.

Life expectancy

In the wild, killer whales can live between 50 and 80 years. One female orca even lived to 103.

In captivity, however, orcas' life expectancies are often cut short. While the actual numbers are highly disputed, PETA argues that the average age of whales who have died in captivity since 1965 (when orcas were first captured and displayed in exhibitions) is just 12-years-old.

Big man on campus

The largest killer whale on record was 32 feet long and weighed 22,000 pounds.

Unique dialects

Every pod has a unique dialect of sounds. So, orcas can recognize calls from members of their own pod, up to several miles away.

Aggression

Though orcas have occasionally shown aggression to humans and each other in captivity, they are not considered a threat to humans in the wild. There have been very few documented cases of orcas attacking people in their natural habitat, none of which were fatal encounters.

Back in the saddle

Orcas have a squiggly gray patch, just below the dorsal fin, called a saddle.

Saddles can either be closed (uniformly gray) or open, with patches of black at their center. The shape and color variations of these saddle patches, however, are totally unique, and can be used to identify individual orcas in the wild.

Kings of the food chain

Killer whales are apex predators. That means that, much like lions in Africa, they sit at the very top of the food chain, and have no natural predators in the ocean.

That is, of course, until humans started hunting them, contaminating their waters, and affecting their food supply. Now, certain groups of killer whales -- like the Southern Resident population, which inhabits the waters near British Columbia and Washington state -- are considered endangered.

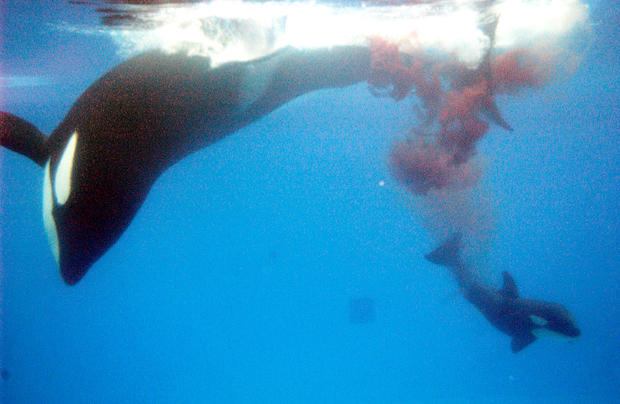

A killer pregnancy

Female orcas give birth every three to ten years, after pregnancies that last 17 months.

This photo was taken just moments after a 28-year-old female orca, named Kasatka, gave birth to a newborn killer whale at SeaWorld San Diego's Shamu Stadium in December 2004. The calf was born weighing between 300 and 350 pounds, measuring between 6 and 7 feet. And we thought humans had it bad!

Families

Orcas are social animals that essentially live in stable families. So, after a mother gives birth, she isn't alone in taking care of her calf. The other adolescent females in the pod help out as well.

Teeth fit for a killer

A killer whale's teeth can be up to four inches long.

A whale of a meal

The average orca weighs about 6 tons, eats approximately 300 pounds of food per day, and clocks in at about three-quarters the length of a school bus.

UV rays

Due to the shallow nature of tanks at marine parks, orcas in captivity spend far more time at the water's surface than their counterparts in the wild. Many experts believe that this increased exposure to UV rays may play a part in shortening captive orcas' life expectancy.

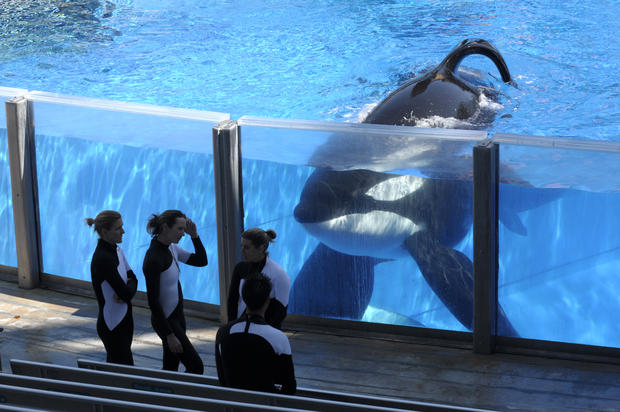

Collapsed dorsal fins

One hundred percent of male orcas in captivity have dorsal fins that are partially or completely collapsed to one side, like the one on Tilikum pictured here. Many of the female orcas in captivity have these collapsed dorsal fins as well.

Though SeaWorld claims, "Neither the shape nor the droop of a whale's dorsal fin are indicators of a killer whale's health or well-being," collapsed dorsal fins are extremely rare in the wild. When they do occur, they are the result of serious injury or environmental contamination. Two male orcas were found with collapsed dorsal fins after they were exposed to the Exxon Valdez oil spill, for example. They both died shortly after.

The world's biggest dolphins

While we call them killer whales, orcas are actually members of the dolphin family.

Echolocation

Orcas communicate using echolocation during hunts. That means they make distinct sounds, which travel underwater until they encounter the object the orcas are looking for. Then, the sounds bounce back, revealing the object's shape, size and location.

Killer whales

Orcas are extremely versatile animals. They prefer cold, coastal waters, but can be found everywhere from the polar regions to the Equator.

Mama's boys

Killer whales stick close to their mothers, living and traveling in her pod, even after they are full-grown.

In captivity, however, financial decisions often sever those family bonds. The documentary, "Blackfish," even highlights one case in which a mother orca was recorded emitting long range calls in a desperate attempt to communicate with a child who had been transferred.

Killer whales

As of October 2015, 58 orcas are living in captivity, in over a dozen different theme parks in eight different countries.

Here, Orca Morgan swims in her tank at the Dolfinarium in Harderwijk, Netherlands. Animal rights activists lost a last ditch appeal in an Amsterdam court to release her back into the wild. As a result, Morgan was transferred to Spanish marine park Loro Parque on Tenerife island instead.

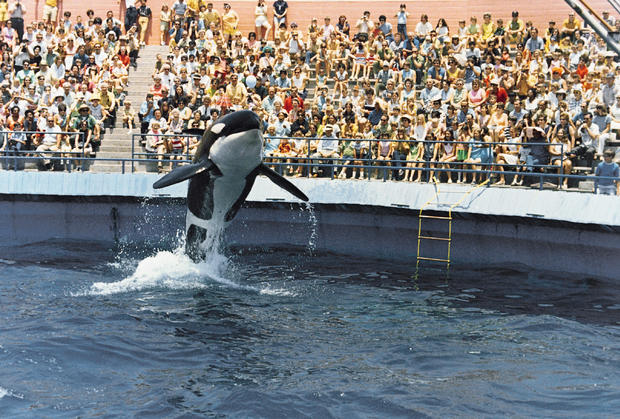

SeaWorld

SeaWorld has three marine mammal parks in the U.S., located in California, Florida and Texas. Killer whales are its main attraction because they are so intelligent that they can be trained to perform amazing tricks during shows.

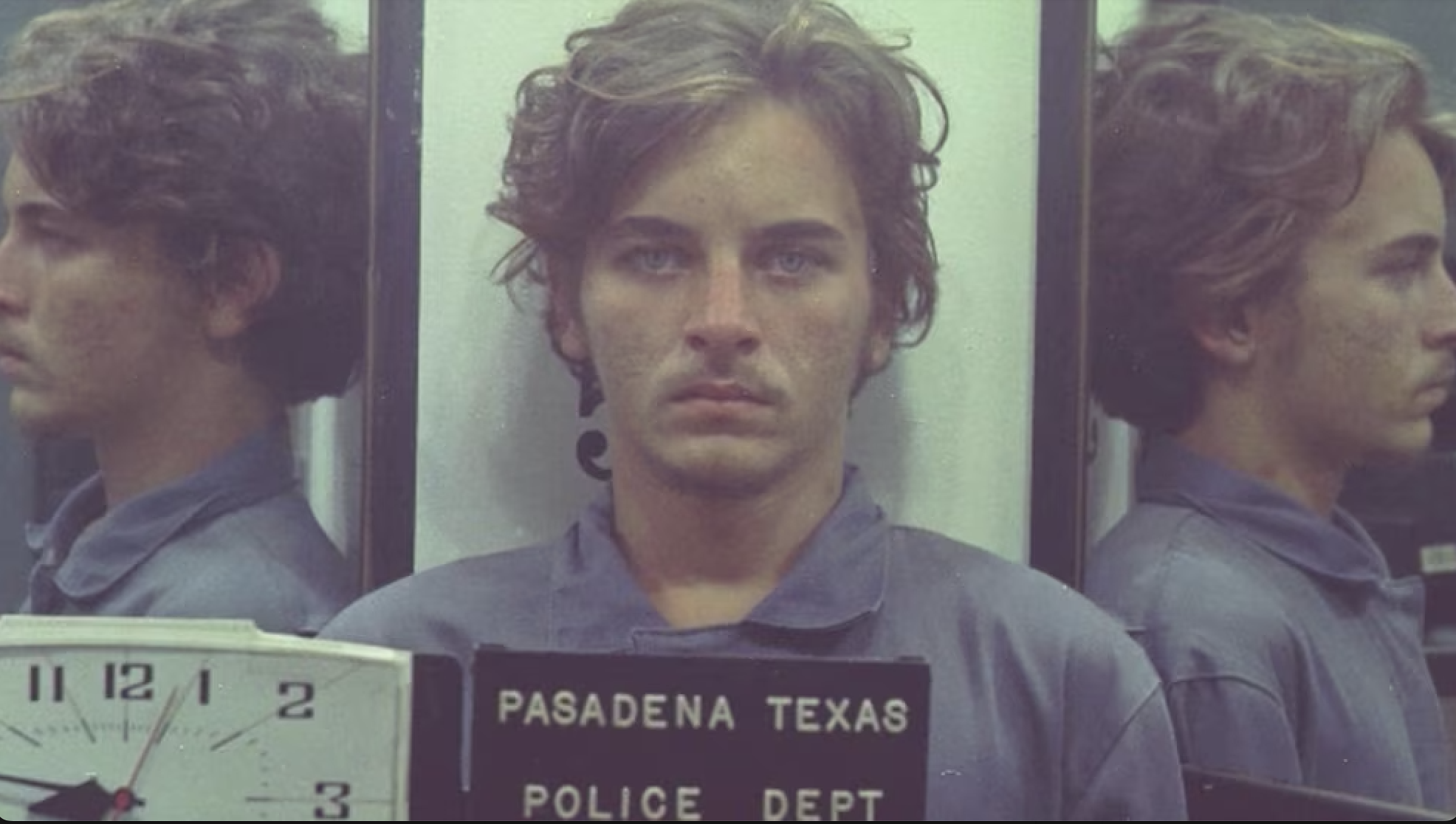

In 2013, however, a film, called "Blackfish," exposed millions of people to the story of Tilikum, one of SeaWorld's captive orcas, who has been involved in the deaths of three people. Since then, SeaWorld has been bleeding money and seen drastically decreased attendance. Now, in late 2015, they are responding to the public's widespread scrutiny by beginning to phase out the Shamu show at their San Diego location. Animal activists, however, believe the move may be too little too late.

SeaWorld's future

In 2017, SeaWorld intends to replace the longstanding whale shows at its San Diego park with a different orca experience that would bring with it "a conservation message inspiring people to act," according to a company document posted on its website.

It remains unclear if the productions will continue at the company's other parks in Orlando, Florida, and San Antonio, Texas. The decision to phase out the shows in San Diego is the result of customer feedback, a company representative said.

"People love companies that have a purpose, even public companies -- I don't have to tell you what Whole Foods stands for. I don't see any reason SeaWorld can't be one of those brands," Joel Manby, SeaWorld's president and CEO, said at an investor's day conference on November 9, 2015. "We're not there today," he added.