Inside the Black Panther Party

Fifty years after the founding of the controversial Black Panther Party (BPP), Stephen Shames' photos give viewers a unique look at the group and its leading figures in the book, "Power to the People: The World of the Black Panthers" (Abrams), by the photographer and Bobby Seale, co-founder and chairman of the BPP, who created a close bond with Shames. Many of the images, from a span of seven years, have not been seen before. Together with the text in the book, which includes interviews, they reveal the complexity of a movement that has been vilified by some and held up as heroic by others.

It's particularly timely as a counterpoint to current events - the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement and the vital discussion on racial justice in America.

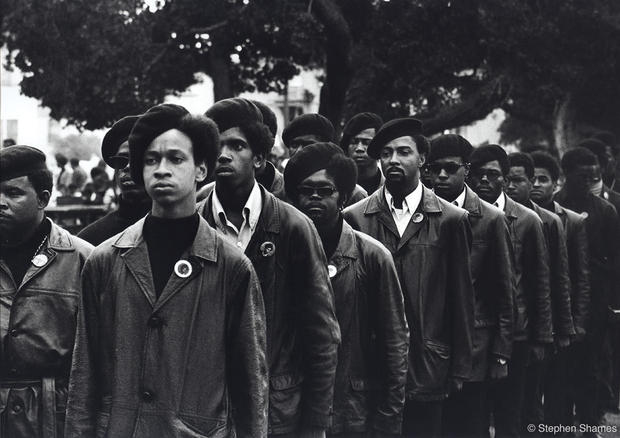

In this photo: Panthers march during a "Free Huey" rally in Oakland, California, 1969. Newton was arrested for allegedly killing an Oakland police officer during a traffic stop, convicted of voluntary manslaughter, and released after an appeal in 1970.

By Radhika Chalasani

Bobby Seale trial

On October 15, 1966, Huey Newton and Bobby Seale founded the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense (which later became simply the Black Panther Party) in Oakland, California. Malcolm X had been assassinated the year before. The turbulent era would include the killing of Rev. Martin Luther King in 1968.

The black nationalist group's goal was revolutionary socialism and their mission included fighting police brutality against blacks. The Director of the FBI J. Edgar Hoover labeled the group "the greatest threat to the internal security of the country." Hoover monitored and harassed the BPP, declaring them a communist group, through the agency's counterintelligence program, COINTELPRO. The FBI used every tactic at its disposal, including infiltrating the organization and the use of force.

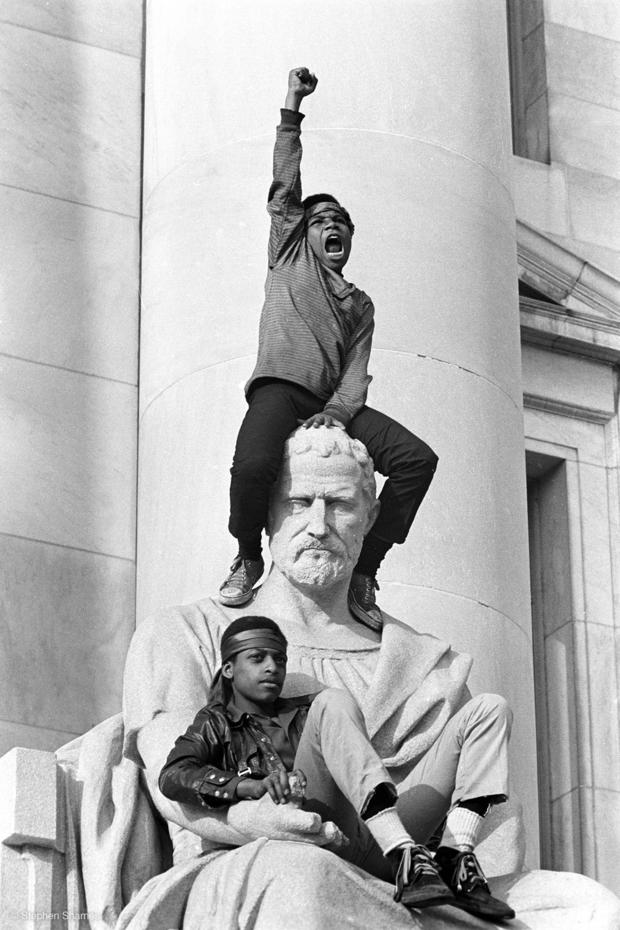

A boy gives a raised fist salute as he and a friend sit on a statue in front of the New Haven County Courthouse at a demonstration during the Bobby Seale and Ericka Huggins trial, in New Haven, Connecticut, May 1, 1970.

Black Panther Party - 1960s

The Black Panther Party had a 10-point platform for black empowerment which addressed social issues such as education and housing. But they also wanted blacks exempt from military service and all African-Americans released from jail, among other political demands.

The group took advantage of California law which allowed people to carry unconcealed guns, to patrol black neighborhoods. Members would show up during police arrests to monitor the situation against abuse.

Their fully-armed appearance at the California State legislature to protest a gun control bill was a bold act that made news across the country.

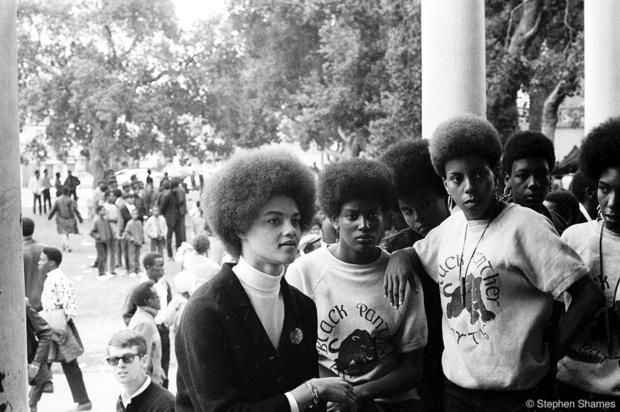

Kathleen Cleaver, communications secretary and the first female member of the party's decision-making Central Committee, talks with Black Panthers from Los Angeles in West Oakland, California, July 28, 1968. Women made up more than half of the BPP by the mid-'70s.

Black Panther Party

After numerous police raids around the country, Panthers fortified their offices, May, 1970. Bags line the walls of the New Haven Panther office to protect against a suspected police raid during the Bobby Seale trial.

Bobby Seale

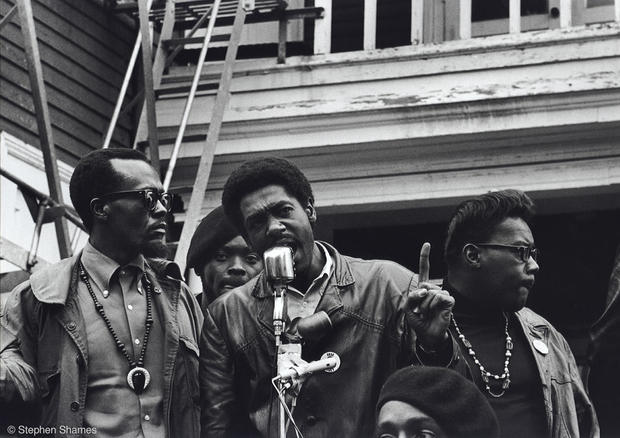

Black Panther chairman and co-founder Bobby Seale speaks at a "Free Huey" rally in DeFremery Park (named Bobby Hutton Park by the Panthers) in West Oakland, California, July 28, 1968. Left of Seale is Bill Brent, who later went to Cuba. Right is Wilford Hol.

Free Huey rally

A "Free Huey" rally in front of the Alameda County Courthouse, in Oakland, California, September 1968.

Angela Davis

Angela Davis, who was a Black Panther for six months, speaks at a "Free Huey" rally in DeFremery Park in Oakland, California, November 12, 1969.

Davis taught political education classes for the party. In 1970, then-California Gov. Ronald Reagan refused to renew her position as a lecturer in philosophy at UCLA because of her association with the BPP.

Her involvement with the imprisoned George Jackson, accused of killing a guard, brought her even more notoriety. She landed on the FBI's Ten Most Wanted Fugitives List.

Black Panther Party

Memorial mural for Jonathan Jackson, who was killed on August 7, 1970, during an attempt to kidnap California Superior Court judge Harold Haley and three others. Jackson intended to exchange Haley for the freedom of his imprisoned brother, George Jackson. Photo: Roxbury, Massachusetts, 1970.

Black Panther Party

Black Panther founders Bobby Seale and Huey Newton stand in front of of the Panthers' National Headquarters in Oakland.

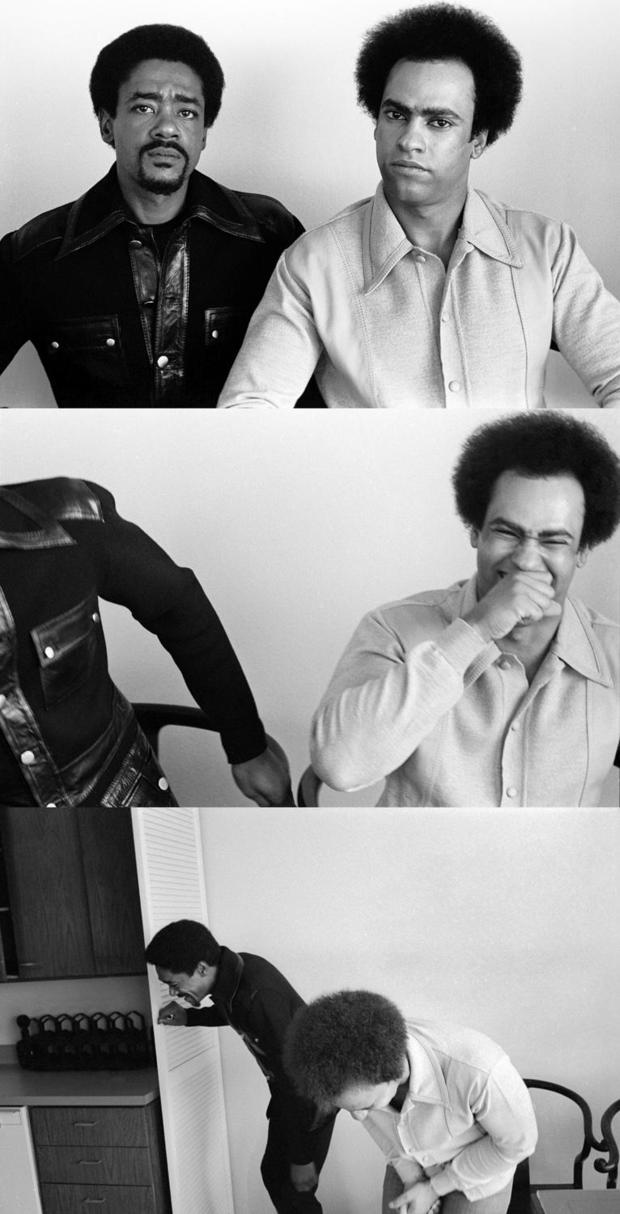

Bobby Seale & Huey Newton

A photo sequence showing Black Panther co-founders Bobby Seale and Huey Newton posing in Huey's penthouse apartment in Oakland.

The Black Panther Party was one of the most influential responses to racism and inequality in American history. The Panthers advocated armed self-defense to counter police brutality, and initiated a program of patrolling the police with guns and law books. Their enduring legacy is their programs, like Free Breakfast for Children, which helped to inspire a national movement of community organizing for economic independence, education, nutrition, and health care.

Black Panther Party

A boy tries on a coat in the Panther office, as part of the Free Clothing Program (one of the Panthers' Survival Programs), Toledo, Ohio, 1970.

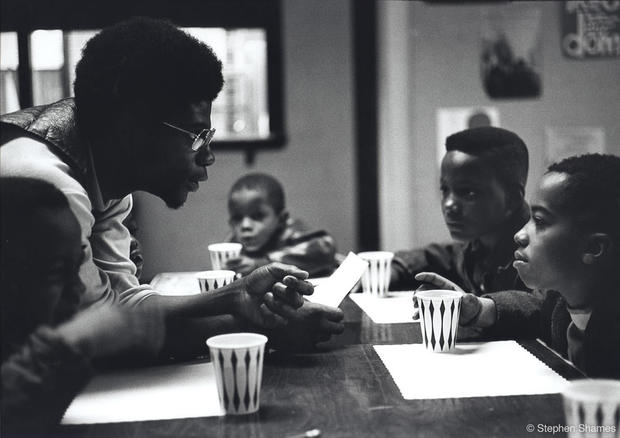

Community program

The Free Breakfast for School Children Program was one of more than 60 programs run by the Panther Party. Other programs included, Free Health Clinics, Free Food, Free Clothing and Shoes, SAFE (escorting seniors so they would not be robbed), and the Oakland Community School, which provided high-level education to 150 children from impoverished urban neighborhoods.

Pictured: A free breakfast program, Chicago, 1970.

Black Panther Party

The Free Breakfast for School Children Program was a community service program run by the Black Panther Party. Inspired by contemporary research about the essential role of breakfast for optimal schooling, the Panthers would cook and serve food to the poor inner city youth of the area. Initiated in January 1969 at St. Augustine's Church in Oakland, the program became so popular that by the end of the year, the Panthers set up kitchens in cities across the US, feeding more than 10,000 children every day before they went to school.

Bobby Seale believed that "no kid should be running around hungry in school," a simple credo that lead FBI director J. Edgar Hoover to call the breakfast program, "the greatest threat to efforts by authorities to neutralize the BPP and destroy what it stands for."

Black Panther Party

Mojo mows the lawn as Black Panthers (and Mojo's dog) stand in the yard of the Black Panther National Headquarters at 1048 Peralta Street, West Oakland, 1971.

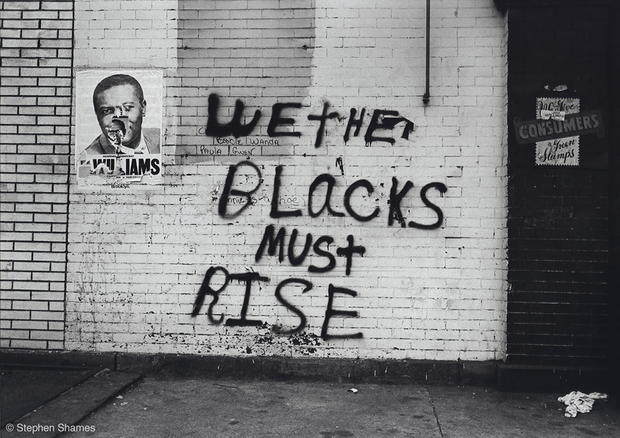

Brooklyn graffiti

Writing on a wall in Brooklyn, New York, 1970: "We the Blacks must rise."

Contrary to the common view that the group was anti-white, the Panthers forged alliances with white activists.

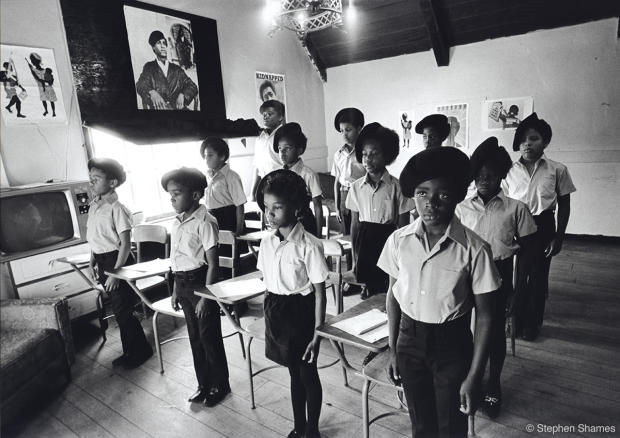

Children of Panther Party

Children in a classroom at the Intercommunal Youth Institute, the Black Panther school, in Oakland, California, 1971.

Black Panther Party

Black Panther children study at the Intercommunal Youth Institute, in Berkeley, Calif., 1972.

In 1970, David Hilliard created the idea for the first full-time liberation day school. This school, and its attendant dormitories in Oakland and Berkeley, was simply called the Children's House. This school concept, directed by Majeda Smith and a team of BPP members, became the way in which sons and daughters of BPP members were educated. Staff and instructors were Black Panther Party members. In 1971 this school moved into a large building in Berkeley and then to the Fruitvale area of Oakland. The Children's House was eventually renamed the Intercommunal Youth Institute. Under the leadership of Brenda Bay, the IYI served BPP families and a few nearby families in the Fruitvale area, maintaining a day school program and dormitory with 50 children, for two years.

Black Panther Party

A woman with a bag of food at the People's Free Food Program, one of the Panther's survival programs, in Palo Alto, Calif., 1972.

Black Panther Party

Two women with bags of food at the People's Free Food Program, one of the Panthers' survival programs, in Palo Alto, California, 1972.

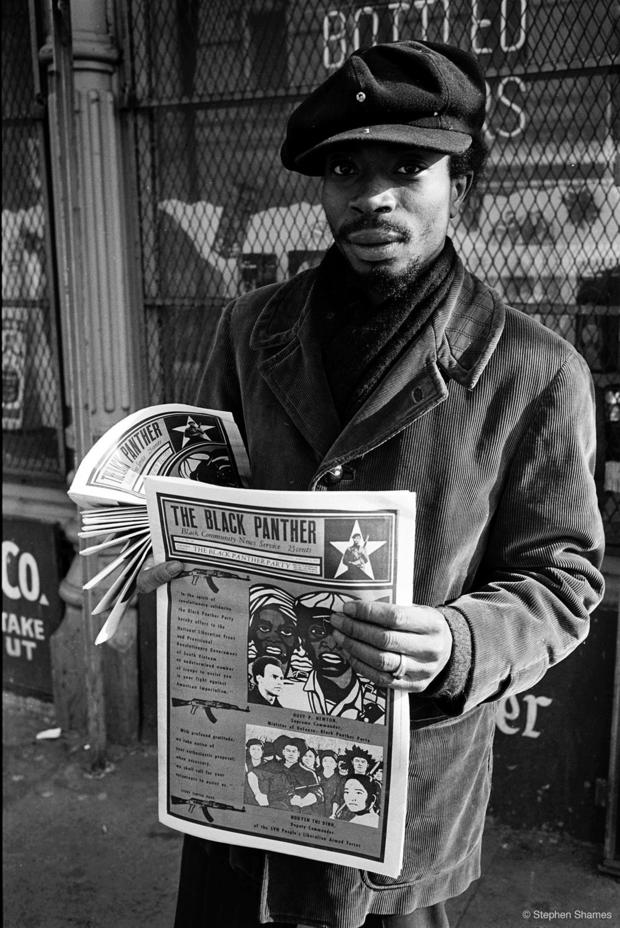

Black Panther newspaper

A party member sells "The Black Panther," the group's newspaper, in the Roxbury section of Boston, Massachusetts, 1970.

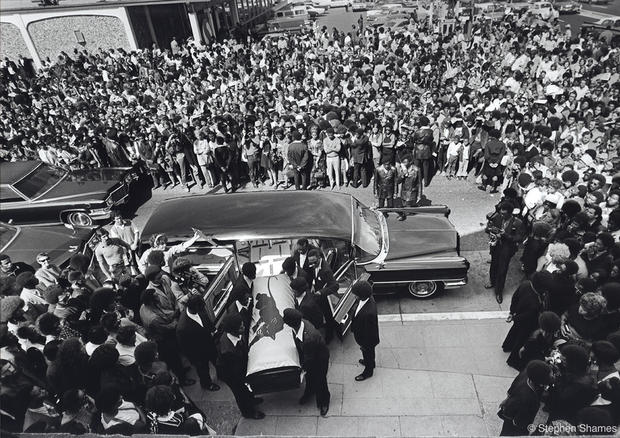

George Jackson's funeral

Black Panthers carry George Jackson's coffin into St. Augustine's Church for his funeral service as a huge crowd watches in Oakland, California, August 28, 1971.

Jackson reportedly joined the BPP after meeting Huey Newton in jail. He was killed during his attempted prison escape in which three guards and two white prisoners were killed. Angela Davis was accused but later acquitted of conspiracy, kidnapping and murder for allegedly supporting Jackson's younger brother Jonathan's deadly courtroom hostage-taking attempt.

Black Panther Party

The funeral of George Jackson at St. Augustine's Church, Oakland, August 28., 1971. Glen Wheeler and Claudia Grayson (known as Sister Sheeba) stand in front; Clark Bailey (known as Santa Rita) has cigarette in his mouth. 2nd row: Van Hilliard (known as Van Junior), John Seale (Bobby's brother, back to us), and Van Taylor.

In 1961, George Jackson was convicted of armed robbery (as a teenager stealing $70 at gunpoint from a gas station) and sentenced to serve one year to life in prison. During his first years at San Quentin State Prison, Jackson became involved in revolutionary activity, as well as assaults on guards and fellow inmates. Jackson was killed on August 21, 1971, during a riot in the maximum security prison.

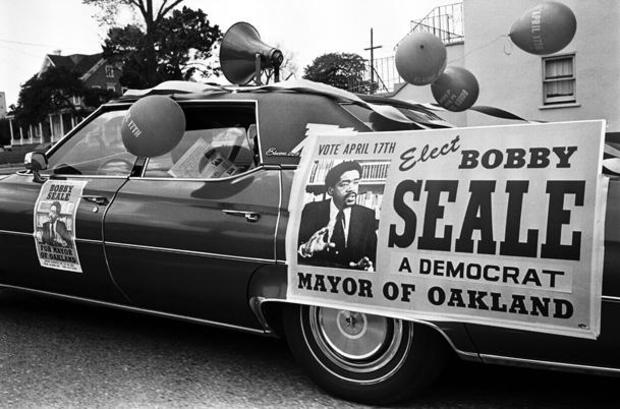

Black Panther Party

In 1970, Bobby Seale and seven others were charged with conspiracy to incite riots for protesting during the 1968 Democratic National Convention. He was sentenced to four years. Seale was also charged with ordering the murder of 19-year-old Alex Rackley, a Panther was suspected of being an FBI informant, but that trial ended in a hung jury.

Upon his release from prison, Seale renounced violence, and in 1973 ran for mayor of Oakland. He received the second-most votes in a field of nine candidates, ultimately losing in a run-off against incumbent Mayor John Reading.

The Black Panther Party's 1972 voter registration drive put several thousand new voters on the books. That registration drive would help Lionel Wilson became the first Black mayor of Oakland, in 1977.

The Black Panther Party dissolved in 1982.