Cocaine: A brief history of blow

What's the most abused illicit drug in the U.S.? After marijuana, it's cocaine. Almost 15 percent of Americans have tried coke, and 6 percent of high school seniors have gotten high from the drug. But if you think cocaine use is just a modern vice, think again. It's been around for thousands of years and has been promoted not just by dope dealers but also by doctors - including some prominent names that might surprise you.

Want to take a trip down the memory lane of cocaine? With the help of Dr. Howard Markel, author of the new book An Anatomy of Addiction, we've put together a brief history of blow...

Earliest addicts

Are coca leaves divine? That's what the Incas around the sixth century concluded after discovering the abundant coca bushes found along the Andes Mountains in South America. Incan men and women used cocaine in rituals, and are believed to have carried coca leaves in small pouches, always ready for a chew.

Cocaine craze hits Europe

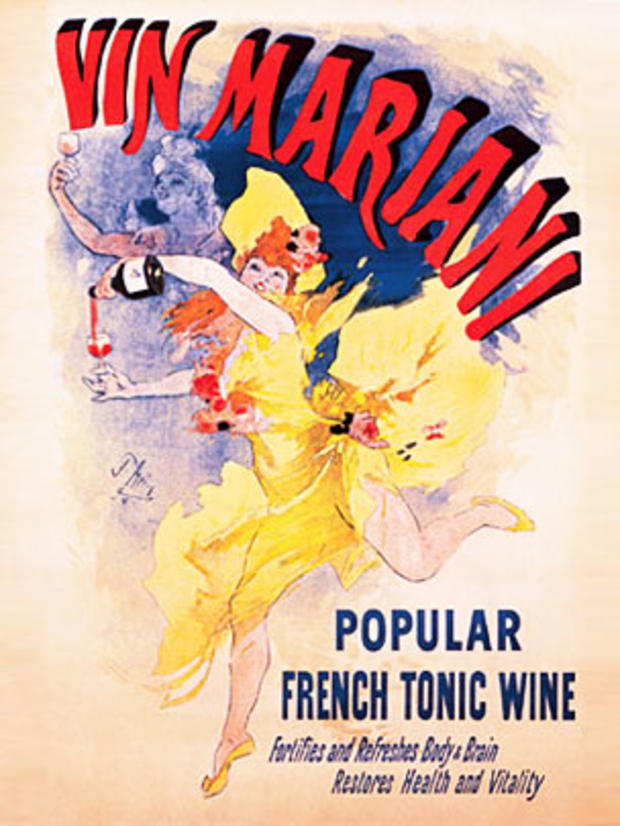

Coca leaves became a consumer product thanks to a French chemist named Angelo Mariani. In 1863, he combined red wine and cocaine to produce a medicinal potion he called Vin Mariani. "It is a stimulant for the fatigued and overworked body and brain, it prevents malaria, influenza and wasting diseases," Mariani claimed. The tonic became wildly popular all over Europe.

Over the years, Mariani introduced all sorts of cocaine-laced spinoffs, including teas, throat lozenges, cigars, cigarettes - and even Mariani margarine.

Cocaine captures doctors' interest

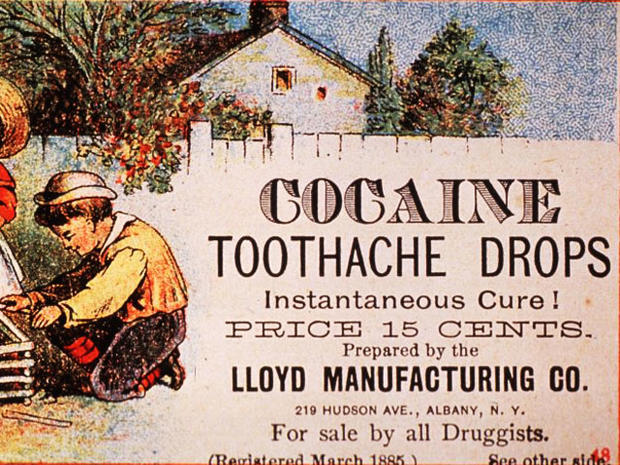

Doctors got a taste of cocaine and were impressed. Medical journals touted it, saying it could cure everything from flatulence, hysteria, hypochondria, and back pain, to muscle aches, nervous dispositions, and fatigue.

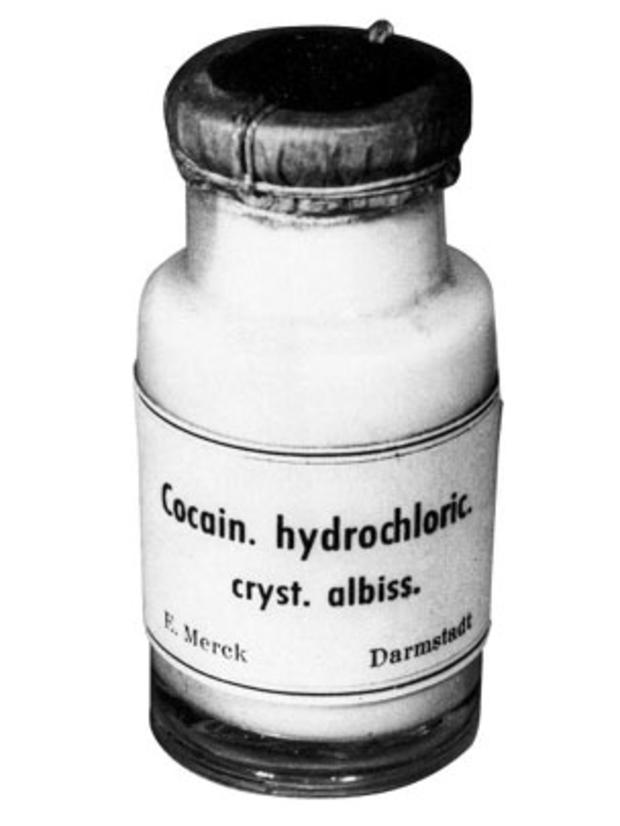

Big drug companies, including Parke, Davis, Merck, Boehringer, and Squibb started making cocaine-containing products - like this vial of cocaine hydrochloride circa 1884 shown here - and sales took off.

"Cocaine was the miracle drug of the 1880s - doctors thought it would cure everything under the sun and patients clamored for the stuff," Dr. Markel says.

America, meet cocaine

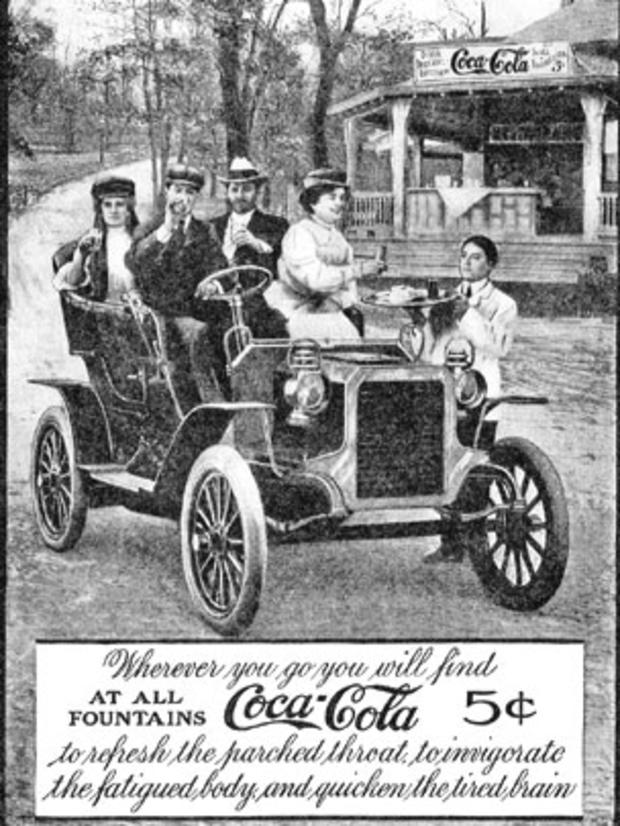

Americans may have one John Styth Pemberton to blame for its cocaine addiction. After the war, the Civil War veteran started using morphine to kill the pain caused by his injuries - and became addicted. He read that cocaine could help cure "morphinism," and began producing a wine-based tonic that contained coke. When Georgia banned alcohol, he mixed cocaine with cola nut extract and soda water, and - voila - Coca-Cola (shown here in a 1905 ad) was born.

Pemberton claimed his "health drink" could cure impotence, headaches, and morphine addiction. Coca-Cola is still made from coca leaves - but the cocaine has been chemically extracted.

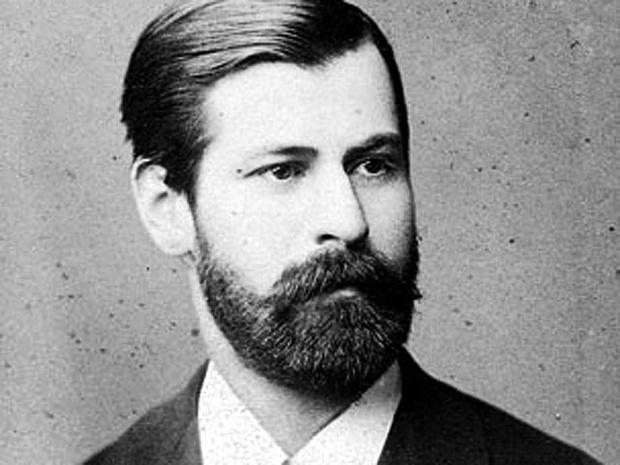

Freud falls for cocaine

Sigmund Freud wasn't just the father of psychoanalysis. He was also one of cocaine's leading medical advocates. Who was his favorite test subject? Sigmund himself.

Freud also recommended coke to his friend Ernst Fleischl-Marxow, a Viennese doctor who was battling an addiction to morphine. But Freud's help may have backfired. Fleischl-Marxow became addicted to both drugs and died seven years later, at the age of 45.

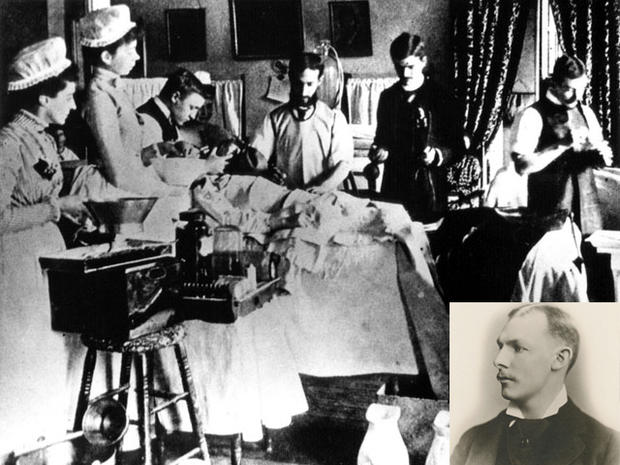

Meet a daredevil young surgeon named Halsted

Freud wasn't the only top doc back in the day to fall into coke's clutches. Dr. William S. Halsted, a prominent surgeon associated with New York City's Bellevue Hospital in the 1880s, was a risk-taker - he once famously removed his mother's gallbladder on her kitchen table. He started experimenting with cocaine to satisfy his own scientific curiosity.

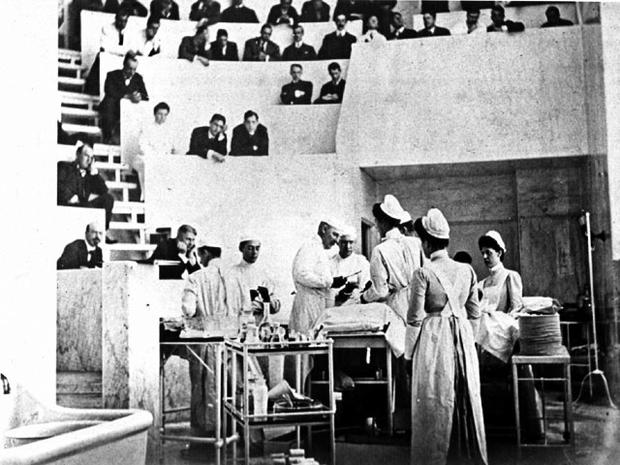

Here's a photo of an operation at Bellevue at the time (with Halsted inset).

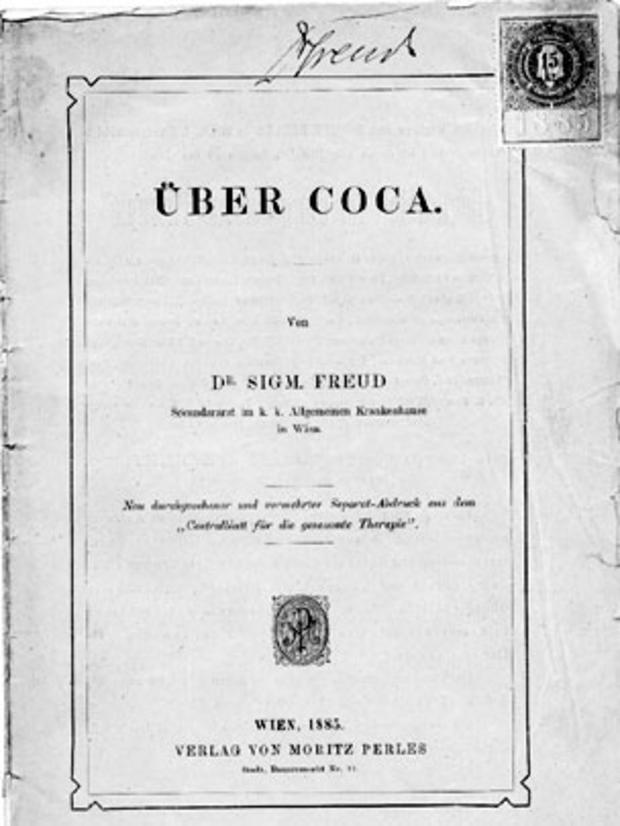

Freud publishes "Uber Coca"

Freud's first major addition to the medical literature dealt not with psychoanalysis but with cocaine. "Uber Coca," was an 1885 tract that erroneously argued that cocaine was so effective at treating morphine and alcohol abuse that "inebriate asylums can be entirely dispensed with."

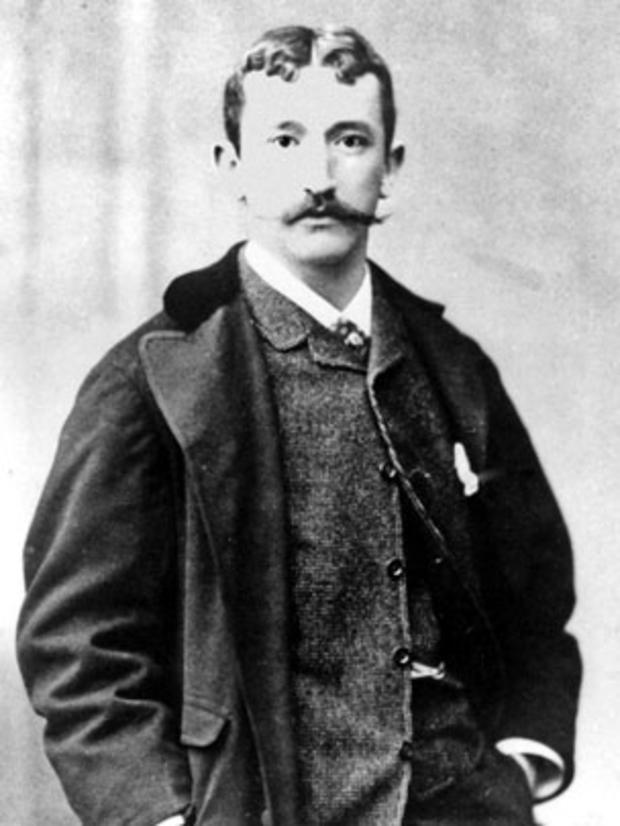

Cocaine as anesthetic

Freud's colleague Dr. Karl Koller, an ophthalmology intern at Vienna General Hospital, was the first to write about cocaine's anesthetic properties. Soon thereafter, cocaine made headlines around the globe and doctors worldwide capitalized on the new miracle drug. Freud was less than thrilled about Koller stealing the spotlight.

Here's Koller in 1884, at the age of 27.

Daring doctor turns to cocaine

Like Freud, Halsted used his own body to study cocaine's effects, injecting the drug into his arm and occasionally sniffing it to fight fatigue. He and his pals were taking cocaine for theater trips, dances, and bowling outings. Soon they became full-fledged addicts, injecting the drug exclusively.

Here's Halsted in the Johns Hopkins operating room, around 1905.

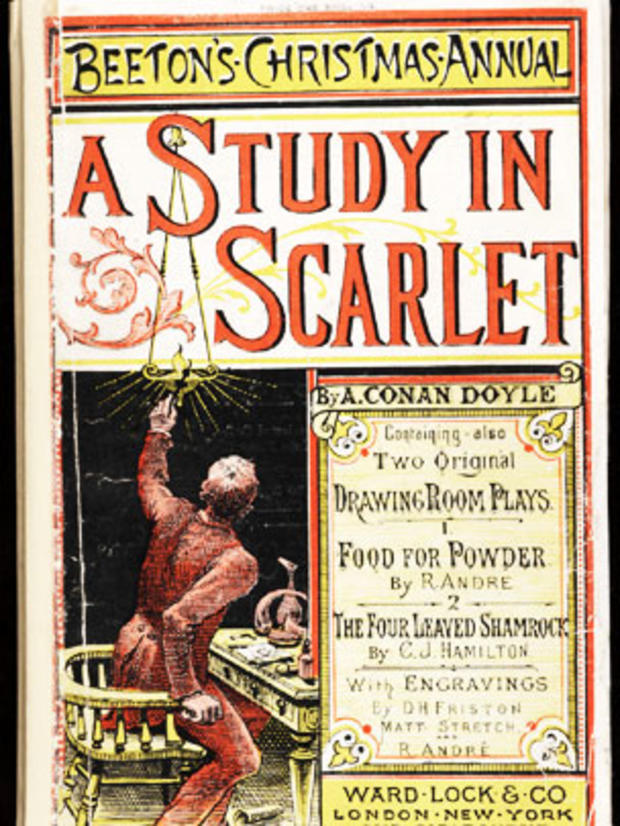

Sherlock Holmes and snow

When did cocaine become part of popular culture? Back in 1887, when a young British doctor named Arthur Conan Doyle published the first Sherlock Holmes novel, "A Study in Scarlet." In the book, the sleuth injects himself with cocaine to unwind after difficult cases.

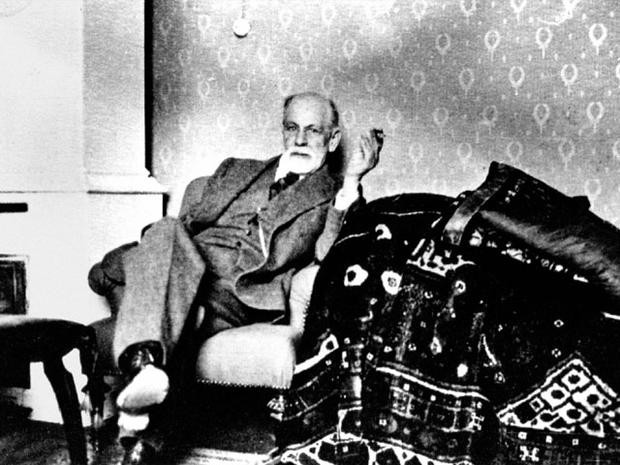

Freud kicks his coke habit

Freud scholars believe he kicked cocaine around the time of his father's death, in 1886. At the time, he wrote in a letter, "Next time I shall write more and in greater detail, incidentally, the cocaine brush has been completely put aside."

Here's Freud with his famous couch, around 1932.

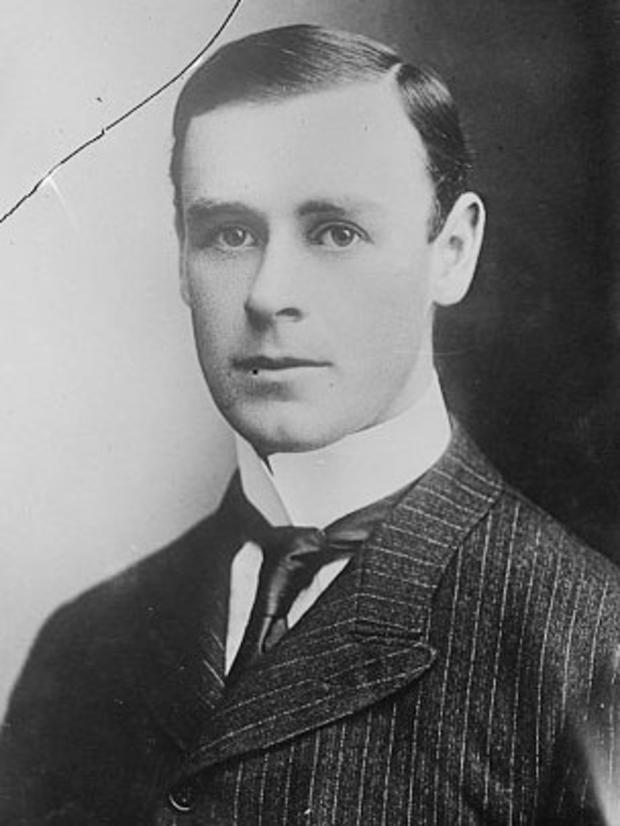

Congress votes to control coke

The nation took notice of drug addiction's sweeping effects, and tried to curtail it with the passage of the Harrison Narcotics Act. Named for its sponsor, New York Representative Francis B. Harrison (pictured), the act regulated and taxed those who produced, imported and distributed opiate drugs including opium, morphine, heroin, and codeine, as well as cocaine.

Halsted is a closet addict

What happened to William Halsted? He was a cocaine and morphine addict until the very end. One can only imagine the physical and mental toll 38 years of secretive drug abuse took on the brilliant surgeon. Halsted died in 1922.

Cocaine goes underground

The Harrison Act didn't quite do what its sponsor had hoped. Cocaine use grew in popularity in the early 20th Century. In 1934, Cole Porter celebrated coke in his hit song "I Get a Kick Out of You," whose lyrics include the following lines: "Some get a kick from cocaine. I'm sure that if I took even one sniff that would bore me terrifically, too. Yet, I get a kick out of you."

Charlie Chaplin (shown here) did his part too, with his character accidentally taking a lot of cocaine in the 1936 film "Modern Times."

Cocaine helps fuel a war on drugs

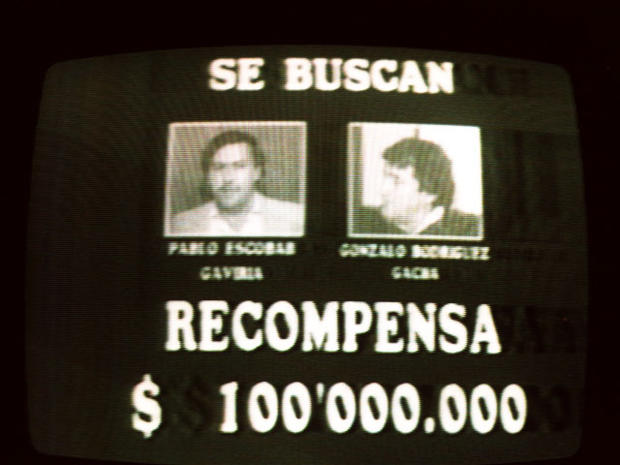

Cocaine use in the U.S. began to dip by the 1940s only to come back with a vengeance in the 1970s. But behind the good times at New York City's Studio 54 disco was the dirty and often deadly world of drug trafficking. Pablo Escobar (shown here in a 1989 Columbian television wanted ad) was a leading drug tycoon until his death in 1993.

Cocaine today

Nearly 5 million Americans used cocaine within the last year - and nearly 2 million have used it in the last month, according to the Office of National Drug Control Policy, . Cocaine also causes about 550,000 trips to the emergency department each year.

"Cocaine abuse and addiction continue to plague our Nation,"says Dr. Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute of Drug Abuse.

Dr. Markel says there's hope, despite these statistics:

"Recent discoveries about the inner workings of the brain and the harmful effects of cocaine offer us unprecedented opportunities for addressing this persistent public health problem."