"Bubble Boy" 40 years later: Look back at heartbreaking case

What's it like to live in a bubble? For some, this means living a sheltered life. But David Vetter, a young boy from Texas, lived out in the real world - in a plastic bubble. Nicknamed "Bubble Boy," David was born in 1971 with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), and was forced to live in a specially constructed sterile plastic bubble from birth until he died at age 12.

Today marks what would have been David's 40th birthday. Now, kids with SCID lead normal lives, thanks to therapy made possible in part by David's own blood cells. A recent report showed that 14 of the 16 children who received this experimental therapy nine years ago are now living full lives.

But what was life like for "Bubble Boy"? Keep clicking to look back at David's heartbreaking story, put together here with the help of Texas Children's Hospital, Baylor College of Medicine, and PBS documentary, "The Boy in the Bubble"...

David was born on September 21 at the Texas Children's Hospital in Houston. After 20 seconds of exposure to the world, he was placed in a plastic isolator bubble.

David wasn't the first child in the family to be born with SCID. Carol Ann and David J. Vetter's first son died in infancy of the disease.

After Carol Ann learned she was to conceive another boy, doctors told her her son would have a one in two chance of being born with SCID - a disease that only affects boys. The Vetters refused an offer to abort their child.

Doctors believed David might outgrow SCID by age two - but he ended up spending his entire life in "bubbles," isolator containment centers designed by NASA engineers.

Is it ethical to raise a child in a bubble? That's what 30 staff members of the Texas Children's Hospital wondered - and eventually agreed that it was.

When he was six, David took his first steps outside of the isolator bubble, thanks to NASA. The space agency designed a special spacesuit for David so he could walk and play outside.

To get from the isolator to the spacesuit, David had to crawl through an insulated tunnel.

Every time David used his suit, helpers had to complete a 24-step pre-excursion hookup and a 28-step suit-donning procedure to keep his environment sterile.

Although the process of putting on the spacesuit was complicated, it was worth it for both David and his mother - who was able to hold her son in her arms for the first time on July 29, 1977 (pictured here).

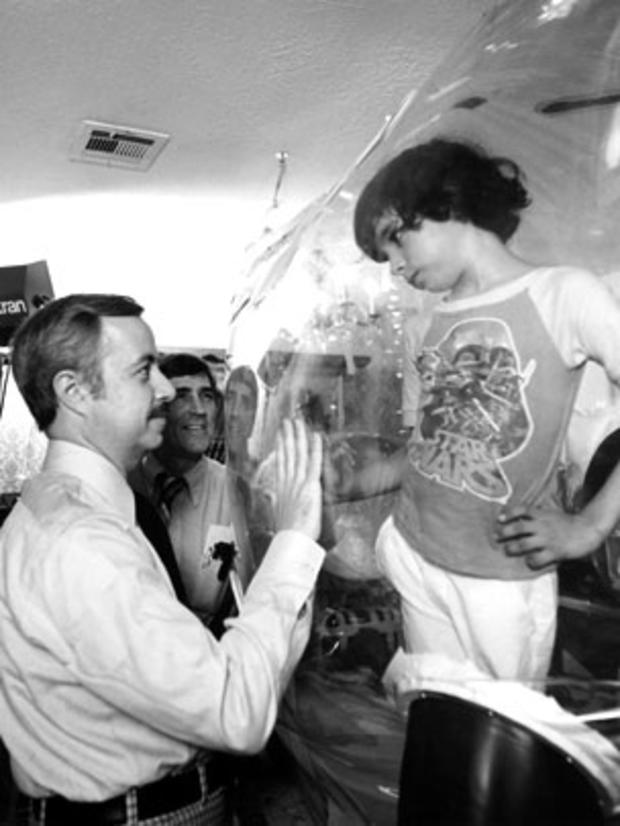

This 1979 photo shows David during a visit with Dr. William Shearer, his primary physician. Dr. Shearer is now chief of the allergy and immunology clinic at Texas Children's Hospital and treats children with SCID today.

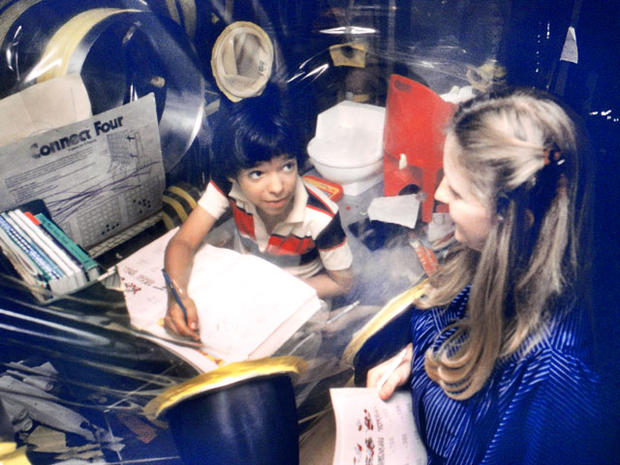

David had school lessons through his bubble and kept up with the rest of the kids his age.

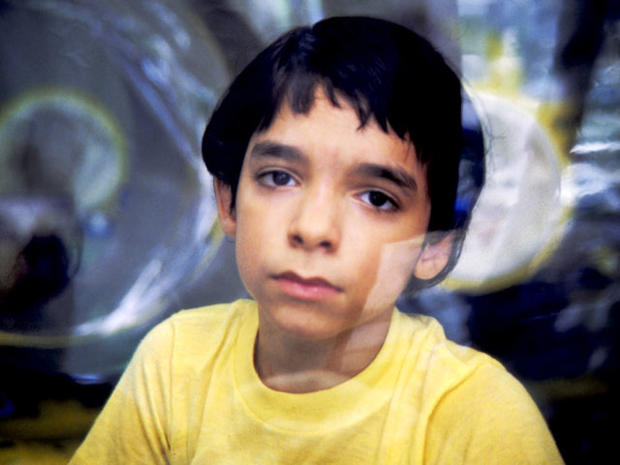

David in his annual photo, taken in September 1979. Immunologists told him that a potential cure would not be available for another 10 years.

This is David's annual photo taken in September 1980.

Here's David in his annual photo taken in September 1982. At 11, he was growing more thoughtful and asked to see the stars. His family took him out to watch the sky for 20 minutes on his birthday.

Immune disorders had typically been treated by bone marrow transfusions among perfect donors only. But in 1983, the Vetters learned of a new procedure that would allow bone marrow transfusions from donors who are not perfectly matched - and agreed to try it. David's sister Katherine donated her marrow. Here, Dr. William Shearer talks to David prior to the procedure.

Four months after receiving the bone marrow transfusion from his sister, David died from lymphoma - a cancer later determined to have been introduced into his system by the Epstein-Barr virus. Shortly after his death, the Texas Children's Allergy and Immunology Clinic opened the David Center - dedicated to research, diagnosis and treatment of immune deficiencies.