Breaking the Nazis' Enigma codes at Bletchley Park

They say that it would have taken at least two more years to defeat the German military in World War II had not some of the Nazis' secret codes fallen into the hands of the Allies.

The Germans had been using Enigma cyphers to scramble their intelligence and military communications and thought Enigma was unbreakable. But work by master codebreakers at Bletchley Park, a secret installation about 45 minutes outside London, eventually proved the Germans wrong.

At the same time, the Nazi high command was sending coded messages using a device called the Lorenz. To solve that, Bletchley Park's code breakers came up with a machine called Colossus (a reconstruction is pictured here).

CNET reporter Daniel Terdiman visited Bletchley Park as part of Road Trip 2011. And last year, as part of Road Trip 2010, he visited the U.S. National Security Agency's National Cryptologic Museum in Ft. Meade, Maryland, where many related items, including a collection of Enigmas, are on display.

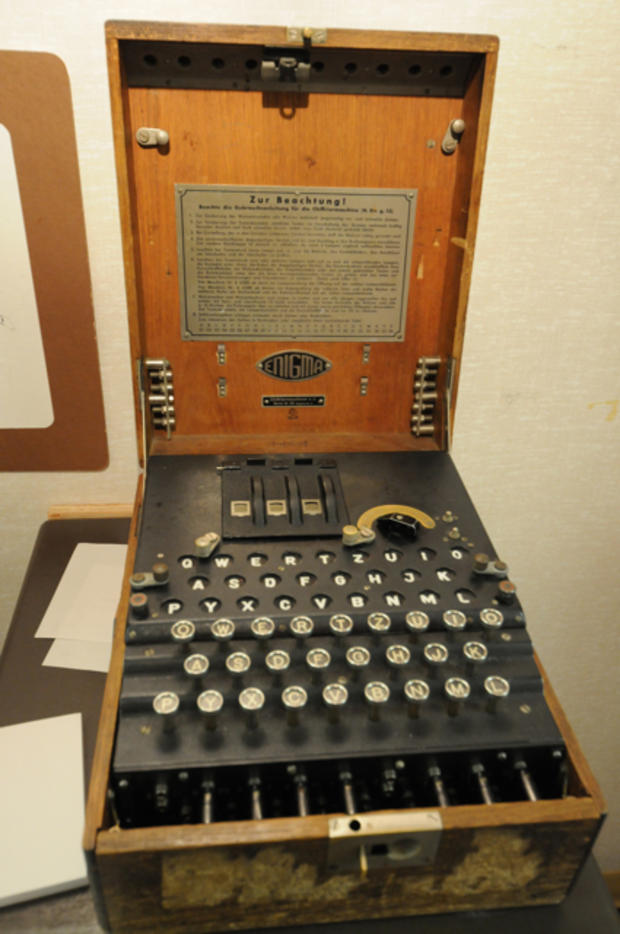

Enigma

This is an Enigma machine, from the collection of the National Cryptologic Museum in Fort Meade, Maryland -- the museum of the U.S. National Security Agency.

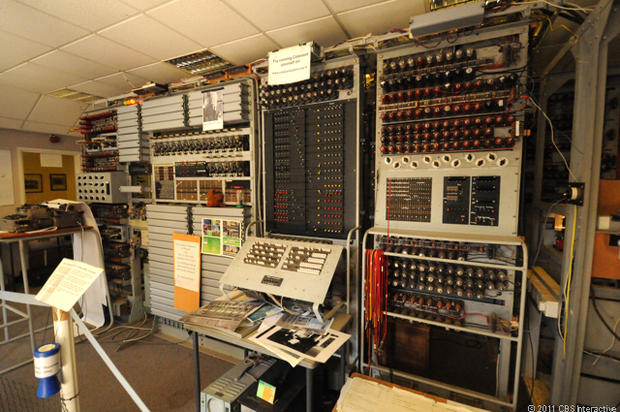

Colossus close-up

To tackle the job of quickly analyzing intercepted German high command messages, leaders at Bletchley Park "called in the help of Tommy Flowers, a brilliant Post Office Electronics Engineer," the museum's website reads. Flowers designed and built Colossus, "the world's first semi-programmable computer." Colossus was delivered in December 1943.

The Germans used a "high security teleprinter cypher machine to enable them to communicate by radio in complete secrecy," writes Bletchley Park scientist Tony Sale on his Codes and Ciphers website. It was called Lorenz, and cracking its code involved "carrying out complex statistical analyses on the intercepted messages," the Bletchley Park museum site reads.

"Colossus could read paper tape at 5,000 characters per second and the paper tape in its wheels traveled at 30 miles per hour. This meant that the huge amount of mathematical work that needed to be done could be carried out in hours, rather than weeks."

This is a closeup of the Colossus rebuild at Bletchley Park today.

Colossus tubes

This is a closeup of some of the 1,500 vacuum tubes used to do the work on Colossus. The machine was built entirely from off-the-shelf Post Office machinery parts.

Behind Colossus

A look at the rear side of Colossus. The rebuild at the National Museum of Computing at Bletchley Park is a fully functional machine that can decrypt Lorenz codes on demand.

Enigma rotors

These are the operational rotors of an Enigma machine.

According to the National Cryptologic Museum in Fort Meade, Md., "The German military issued extra rotors with each machine -- two for Army and Air Force machines and four for Navy. Each rotor was wired differently and identified with a Roman numeral. Setting up a communications net involved selecting the rotors for the day and placing them in the machine in the proper left-to-right order."

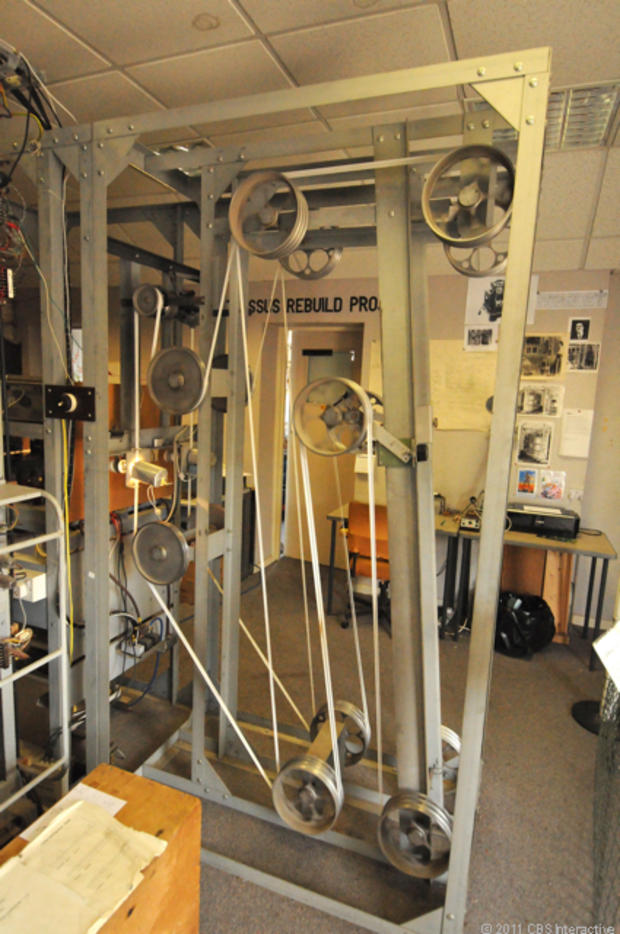

Colossus ticker-tape reader

This is a device attached to Colossus that constantly read characters back into the machine -- because Colossus had no on-board storage. Instead, the tape that was produced by teams at other machines was continuously read back into Colossus until it had the entire message.

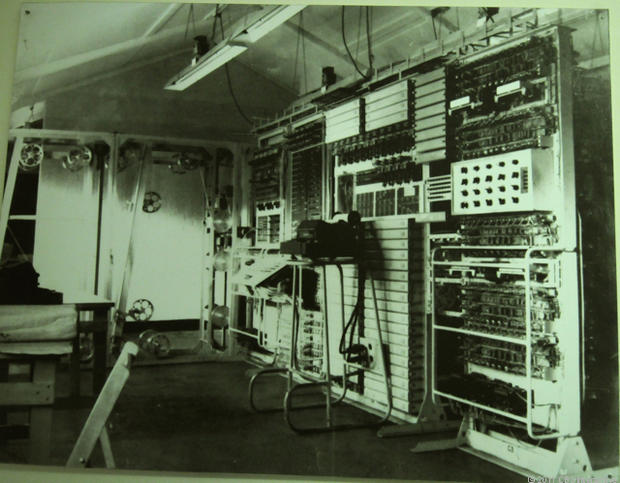

Original Colossus

The rebuild of Colossus was possible because, although the original machine was nearly destroyed, there were at least 11 surviving photographs of it on which to base the reconstruction project.

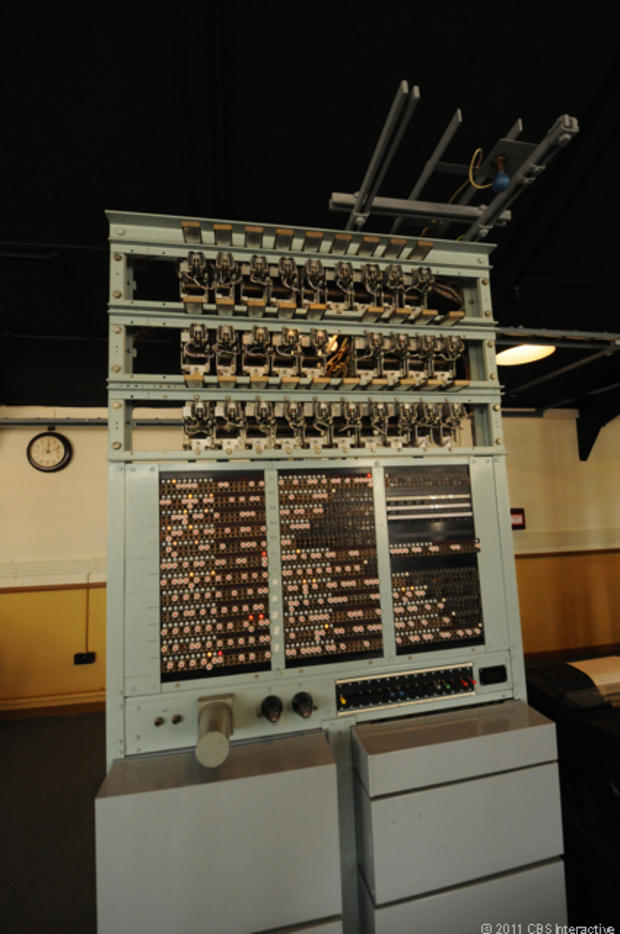

Early intercept machine

This is an earlier version of an intercept machine, which captured the Germans' communications and put out a ticker tape that was then read and its contents input into a second machine, called a "Tunny," for deciphering.

Undulator

This device converted the coded messages captured by the intercept machine into a ticker tape that was then read and its contents typed into a Tunny machine.

Tunny machines

At Bletchley Park during World War II, groups of women would take the ticker tape containing the coded German messages and type the codes into these Tunny machines. The Tunnys would then convert the coded message into a new ticker tape that would then be put through a bombe machine and analyzed.

Heath Robinson

This is part of the Heath Robinson, a successor to the Colossus. It was not successful because it tended to shred the ticker tape as it fed it through its systems. It was called Heath Robinson because it was considered a crazy invention, something that was regularly a part of a 1940s-era cartoon by that name.

Alan Turing's office

This is a re-creation of Alan Turing's office in Hut 8 at Bletchley Park. From this office, Turing directed efforts to break the German high command's codes and in the process may have helped shave two years off World War II.

Pin board

This is a pin board that's part of the Heath Robinson.

Though its many "huts" and "blocks" look rundown and somewhat decrepit today, Bletchley Park was in its day the world's first purpose-built computing center, built specifically to break the Germans' codes and help the Allies defeat the Germans and win World War II.

Test run

This is a test run of the deciphering capabilities of the reconstructed and fully working machines at the National Museum of Computing at Bletchley Park.

Code system

This is the key that the women working the Tunny machines would use to input the Lorenz codes after they'd come off the undulators at the intercept machines.

Uniselector

This is a Uniselector, a rare piece of an original Colossus machine that survived the intentional destruction of the top-secret machines after World War II was over. It was employed in the Tunny machines to simulate a Lorenz cipher machine wheel. The Uniselectors were also built into the Colossus machines.

German Tunny machine

This is a German Tunny machine, displayed at the National Cryptologic Museum in Fort Meade, Md. A cryptographic typewriter, the Tunny offered encryption and decryption, meaning that an operator could type in plain text and get encoded text out. They were built to handle large amounts of text at high speeds. An early version of these machines was called "Swordfish," and, learning that, the Americans and the British began to give fish nicknames to various versions of the machine.

It is a Schlusselzusatz 40 (SZ40), made by the German company Lorenz and used by the German Army for high-level communications. "It provided on-line encryption and decryption of messages and was capable of handling large volumes of traffic at high speed," according to the National Cryptologic Museum. "The Tunny depended on wheels for its encryption/decryption, but unlike Enigma, it did not substitute letters, but instead encrypted elements of the electrically generated 'Baudot Code' used in normal telegraphic transmissions."

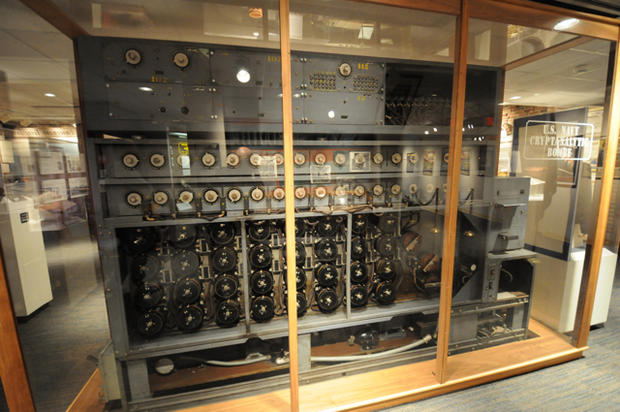

Cryptanalytic bombe

This is a U.S. Navy cryptanalytic bombe. Bletchley Park analysts worked on British-built bombes.

The machines "worked primarily against the German Navy's four-rotor Enigmas. Without the proper settings, the encrypted messages were virtually unbreakable," according to the National Cryptologic Museum. "The bombes took only 20 minutes to complete a run, testing each of the 456,976 possible rotor settings within one wheel order. Different bombes tried different wheel orders, and one of them would have had the final correct settings. When the various U-boat settings were found for the day, the bombe could be switched over to work on the German Army and Air Force three-rotor messages."

George the robot

This is George the robot, built by Tony Sale, a vintage computer specialist who was the original curator or the Bletchley Park Museum.

Sale built George in 1950, and it was the world's first working, walking humanoid, according to Sale. At the time, Sale and George were filmed for British TV, and more recently, when the creators of the "Wallace and Gromit" movies saw the broadcast, they asked for -- and received -- permission to include George in one of their films.

Witch computer

This is the Harwell Dekatron Computer, at the National Museum of Computing at Bletchley Park. Known later in its working life as the Witch Computer, it was built in England at the Atomic Energy Research Establishment in the early 1950s "and is one of the first stored-program computers in the world," according to the museum. "It is a general purpose computer capable of many different jobs and its role...was to assist in the design of Britain's first atomic power stations.

"Before this computer was built, all mathematical calculations at the agency were performed by a team of people using mechanical calculators and slide-rules."

The Millionaire

Built in 1895, this is the "Millionaire," made by Switzerland's H.W. Egll. It was the first calculating machine in history that was capable of doing multiplication instead of just doing repeated addition. Machines like this were common in the insurance industry until the 1930s, according to the museum.

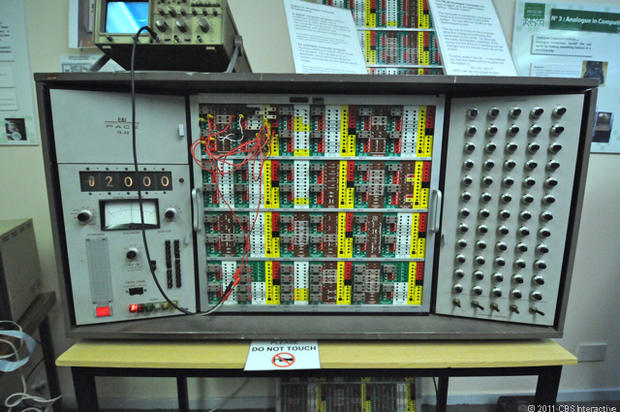

TR-48

This is the TR-48, an early analog computer. To solve a problem, the machine creates "a mathematical model of a problem," according to the museum, "then [plug in] an electronic circuit which simulates the system represented by the mathematical model.

"This is achieved by techniques such as summing, integrating, and applying other functions to create gradually changing voltages within the machine."

PDP-11

This is a PDP 11/34, built in 1976 by Digital Equipment Corporation. It was a 16-bit minicomputer that ran on a single bus system called Unibus.

"The usage of a single bus was quite a departure in terms of computer technology," according to the museum, "as many minicomputers at that time had a separate dedicated I/O bus. The designers at DEC could do without this separate bus by mapping all of the I/O requirements to addresses in memory so that no specialized I/O instructions were needed.

The PDP-11 could use several different kinds of peripherals, such as a disk drive that had as much as 2.5 megabytes of storage space. As well, it had dual 8-inch disk drives that could each store 256 kilobytes of information. It also had a tape drive. This version of the computer "is running the RT-11 single-user real-time operating system," according to the museum.

PDP-8

This is the DEC PDP-8, the predecessor to the PDP-11.

Air Traffic Control radar

This is an air traffic control radar station from 1978 that was once used at London's ATC center near the famous Heathrow airport.

"Along with 30 similar stations, they were manned by the controllers responsible for flights in and out of London Heathrow -- the busiest international airport in the world," according to the museum.

"Two PDP11 computers control each desk.... One is responsible for processing radar data and the other for controlling the display."

Deployed in the 1970s, it was amazingly only retired in 2008.